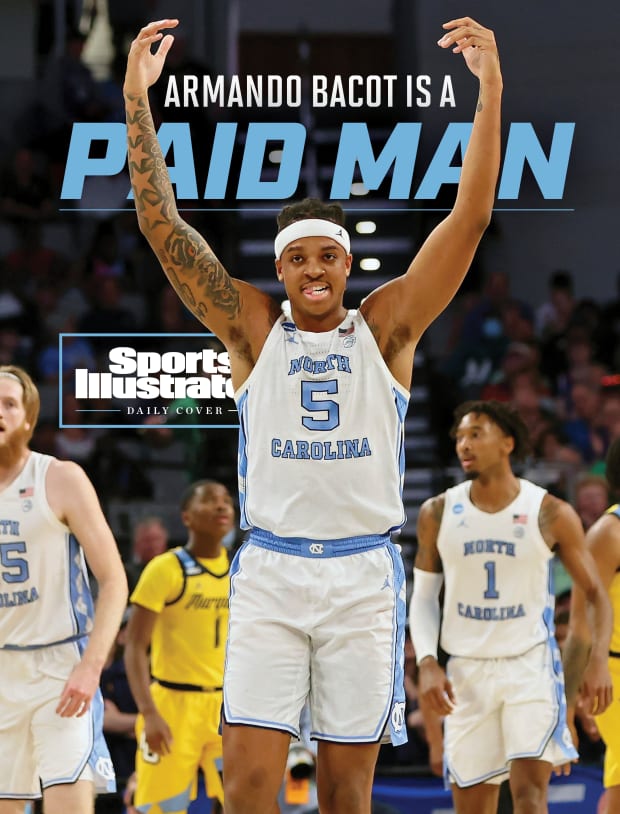

Armando Bacot Jr. is sitting in the Dean Smith Center at the University of North Carolina, explaining that he stayed in school, in part, for the money.

He whips out his phone and pulls up some financial charts. From March 1 through June 8, in the months after he led North Carolina to the national championship game, he made a $21,000 profit selling T-shirts capitalizing on his name, image and likeness. His first endorsement deal, which he signed with Jimmy’s Famous Seafood last summer, was worth five figures. He has since signed with a thoroughbred farm in Kentucky called Town and Country Farms and a technology consulting firm called CapTech, in addition to a card deal with Topps. He does promotional work for Me Fine, a social-services charity, and he took a paid acting role on the Netflix show Outer Banks.

He has delivered more than 100 videos through Cameo, charging $95 for individuals and $350 for businesses. He has a burger named after him as part of an endorsement deal with Town Hall Burger and Beer in Chapel Hill—though, to his embarrassment, the exact toppings elude him at the moment. Told that it’s O.K., he probably didn’t come up with the recipe himself, he says: “I did. That’s why it’s bad that I don’t remember.”

Kevin Jairaj/USA Today Sports

Well, it’s been a busy year. The 6' 10" forward-center, who turned 22 right around the time he finished his junior season, says that between North Carolina’s run to the title game in March and sitting down with SI in early June, he was offered a mixture of deals “pushing the six-figure mark.” His mom, Christie Lomax, estimates that his NIL income this year will be “definitely past half a million.”

Armando knows he would not have been a first-round pick in this week’s NBA draft. He might not have been drafted at all. But he also says: “I know a lot of players [in the draft] that I feel like I'm better than.” Fringe prospects leave school all the time. He could have been one of them.

Without NIL, his mom, a real estate broker, would have encouraged him to turn pro. “He was ready physically and mentally,” she says—and he still would have found time to finish his degree from UNC’s prestigious Kenan-Flagler Business School.

But with NIL? Armando says that staying in school was “a no-brainer. I get a chance to get better, get my degree, be around all my friends and then also make a lot of money.”

So much of the NIL conversation feels like an argument between college basketball’s past and its future. Once it was about getting an education, and now it’s about getting paid. Bacot is proof that college basketball can be about both.

When Armando Bacot was a little boy, he asked his grandmother to take him to GameStop, the video game store. She said O.K., and when she picked him up at his house, he brought a suitcase outside. Inside were various consoles and games that he wanted to sell for cash.

Sometimes he would buy bulk candy with his mom at Sam’s Club and sell the pieces individually for profit. When he was 10, Bitcoin started trading publicly, and his mom promises this is true: “He was begging me, ‘Mom, it’s gonna take over.’ I’m like, ‘I don’t understand it.’ He begged me, and I did not buy any Bitcoin.” As a teen, Armando would save his money for his father, an auto dealer, to buy used cars at auction, and then Armando would turn and sell them for a profit, which he used to do the same thing all over again.

All the while, he was developing into one of the nation’s top 30 recruits, and then, three years ago, the young businessman made a bold decision: He turned down the money. Bacot says that some programs offered him a lot more than a scholarship, in violation of NCAA rules.

“You get these huge offers,” Bacot says. “For me, it was more about fit and going to a good school, because I know eventually the money will come. But, yeah, that was a thing. You know, it’s everywhere. You would hear huge numbers, like six-figure numbers from schools.”

Directly from their coaching staff?

“Yeah.”

And they made it clear that you could get six figures?

“One hundred percent.”

“Looking back at it,” he says, “I’m surprised I didn’t look into it more, but I was just so wrapped up in playing at Carolina, being able to develop here, the whole school thing.”

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

Since then, three years in the ACC have shaped his perspective on what college athletes are worth. During the 2021 NCAA tournament, held entirely in Indiana before COVID-19 vaccines were widely available, he was part of a players’ coalition “trying to figure out a way for players to get paid for playing in the tournament during COVID. It never got far enough because [there] just wasn't enough time.”

Still, he says players should choose a college “based upon the school and not just money.” He believes in NIL’s intent, not all of its perversions.

“Something just don’t sit right with me with some players making more money than [their] coaches,” he says. “I don’t know if I’m a fan of that. … I don’t think that’s a good thing. And I think it’s too easy for players to move around and schools bid on them—I don’t think that’s good for college.

“I think [there] should be some type of rules where you can’t recruit a player and say, ‘If you come here, I'll give you … .’ Especially in the transfer portal. I don't think you should be able to bid on players.”

Informed that he sounds a bit like a coach, he laughs and then takes an honest look at himself. Fact is: He doesn’t need to shop for a better or better-paying gig; he’s already a star at a blueblood college where “just the name of the school helps me,” he says. “I guess that is hypocritical. If I was [transferring] from a mid-major … I guess I probably would go to the highest bidder too.”

So, how do we stop this?

“I really don’t know. I guess that’s why you see so many changes in the NCAA—people stepping down and leaving, and coaches leaving—because it’s just the wild, Wild West.”

Hubert Davis played for Dean Smith, he coached under Roy Williams, and he became the head coach at North Carolina 77 days before the Supreme Court ruled that athletes could profit off of their name, image and likeness. His job is to retain what made the Heels great while adapting to college basketball’s new world. Complaining about the wild, Wild West will get him nowhere. While many coaches bemoan the chaos that NIL and the transfer portal have wrought, Davis just says, “The chaotic part is: It’s different.”

Davis believes the fluid transfer system means that by finding established players to fill roster holes instead of just projecting how high school sophomores will perform in five years, “you can actually build a team.” After the NIL ruling was announced, he told his players they needed three factors to cash in. One: the platform UNC provides. “There are very few programs at our level, but nobody is higher than us,” Davis says. Two: They had to play well. And three: They needed team success.

His best player understood all of this implicitly. After grabbing 22 rebounds against Virginia on Jan. 8, Bacot texted his business adviser, Daniel Hennes: Tell windex i said wassup haha.

The glass-cleaning giant still has not come through with a deal. Neither has Crocs, one of Bacot’s dream NIL partners. (Imagine size-18 Carolina-blue Crocs, with tar painted on the heels.) But Bacot kept focusing on Davis’s three factors, and he arrived at Cameron Indoor Stadium in early March, for Mike Krzyzewski’s last home game with Duke, possessing the kind of competitive rage that a 100-year-old college basketball rivalry demands.

“Before the game, I told the guys, ‘We’re gonna win, or there’s gonna be a fight,’” Bacot says. “Something was gonna go down that night. We was gonna win the game, or we was gonna go out swinging. I mean that literally.”

You know, Armando: A brawl might not have been so good for that endorsement career. …

“Yeah,” he says. “But it was like a pride thing.”

Pride, but not hate. The shops on Franklin St. in Chapel Hill sell a slew of T-shirts mocking Coach K as Coach L, for his two late-year losses to UNC this year, but Bacot says he likes Krzyzewski. Before the NCAA tournament he went out to dinner with Coach K’s grandson, Duke walk-on Michael Savarino. And he has been friends with Duke’s recently departed star Mark Williams, an old AAU teammate from Virginia, for most of his life.

Chris Keane/Sports Illustrated

In between those two recent wins over Duke, the Heels upset No. 1 seed Baylor in the NCAA tournament, after which Bacot texted Hennes, “We’re gonna be rolling with deals. Everyone wants to work with us 😂.”

Critics might hold this up as an example of a player with the wrong priorities. Bacot’s NIL deals, though, have only reinforced the right ones. He entered the year knowing he had to show shooting range to impress NBA scouts but he says that whenever he has a chance to shoot a long jumper, “I feel like I’m settling.” He prefers passing, cutting to the rim and getting into position to rebound. He thinks that’s best for Carolina. Now it is also lucrative. Instead of showcasing his talents for the pros, Bacot hid some of them.

“He can really shoot the three,” Davis says. “He can dribble the ball and make plays off the bounce. But one of the things that Armando has done that most kids don’t do: He doesn’t go away from what he does [best] at an elite level. He rebounds and he defends. The one thing that 100% translates from college to the NBA is rebounding and defense.”

Davis is adamant that Bacot will be “a first-round draft pick next year.” The NBA has soured on traditional big guys who are limited defensively; it just takes one screen to force a switch and exploit them. But Bacot is comfortable guarding on the perimeter. “Armando can easily do that,” Davis says. “He’s great at that, and he’s a dynamic roller to the rim. He’s really good at finishing around the basket with either hand.”

Near the end of UNC’s national semifinal win over Duke, Bacot sprained his right ankle. Davis says, “I did tell him a number of times: You need to be honest with me. If I see you out there and it looks like it’s going to hurt you, I’m going to take you out. I was expecting him to play, but I was 100% ready to sit him, and I was completely at peace with that.”

During warmups two days later, Bacot couldn’t jump. He says, “I started freaking out.” He went to a private area of the Superdome, so nobody would see him hobbling around. Then he came back out and played 38 minutes, scoring 15 points and grabbing 15 rebounds. North Carolina lost to Kansas, but it was a performance that would hold up in any era.

A dozen years after he took that suitcase to GameStop, Armando Bacot has not come close to fumbling the bag. He says that, though he considers himself a buy-and-hold investor, he made more than $20,000 on AMC stock when it caught fire, and he’s earned “over five figures” investing in Tesla—enough, combined, to buy a new Tesla, which he has not done. (He doesn’t own a car at all. “It depreciates,” his mom says.) Armando, his mom and his oldest sister, A’mari, have a running contest to see who can end each year with the highest credit rating. A’mari is the reigning champ.

Armando, meanwhile, has been selectively aggressive in pursuing NIL deals. He finds companies that interest him, DMs them on social media, forms a relationship, then has Hennes negotiate a deal. With each, he asks for a clause in his contract that gives him some time with the company’s CEO. He licenses his image to the T-shirt shops on Franklin St., but he also hired a student to design shirts that he could sell himself on his personal website. Christie even packages and ships them. “My mom, she’s already busy as crap, bless her soul,” he says, “but I got that business mindset. I’d rather just cut the middleman out.” (Bacot prints his shirts in limited batches, to avoid sitting on inventory and to create the aura of exclusivity. The shirts sell for $40, and $25 of that is profit.)

Bacot and Hennes have a few simple guidelines they think every college athlete should follow: Don’t sign deals in perpetuity. Be very careful about exclusives. Know your worth. Retain the right to archive social-media posts, so your feed is not just a relentless stream of ads.

“You see it every year,” Bacot says. “They leave faster than [they should]. They may get drafted, but then they float around the G league. … From there, he’s just a mystery man. I want to go when it feels right and I’m my best self.”

Bacot will enter his senior season hoping for a national championship, because he is conscious of his place in UNC history, and also for a deal with the restaurant chain Raising Cane’s, because he loves their chicken fingers. He has a coach, too, who vows to “call specific plays so [Armando] knows, ‘This is the time I want you to shoot it.’”

In the fall, he can celebrate wins at Town Hall Burger and Beer by biting into a Mondo Burger (beef, onion straws, applewood smoked bacon, barbecue sauce, smoked gouda and lettuce, all on a brioche bun), or he can go home to his $2,000-a-month apartment and take advantage of the one true splurge he is planning: a personal chef. It’s a good life, and he thinks despite all the hand-wringing, NIL is good for the sport. More players will stay longer. They will be happier.

“College basketball’s gonna be on fire these next few years,” he says, the investor recognizing a depressed stock as a growth opportunity.