NASA's Fermi gamma-ray space telescope has examined what may have been the most powerful explosion since the Big Bang, discovering a hitherto unseen feature. The feature could be the result of matter and antimatter particles annihilating at 99.9% the speed of light.

The blast was an example of a gamma-ray burst (GRB); when it was first seen on Oct. 9, 2022, by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, it was designated GRB 221009A. The power of the GRB was soon revealed, and it earned the nickname the Brightest Of All Time or the "BOAT."

"As long as we have been able to detect GRBs, there is no question that this GRB is the brightest we have ever witnessed by a factor of 10 or more," Wen-fai Fong, an associate professor of physics and astronomy and leader of the Fong Group at Northwestern and one of the discoverers of the BOAT explained around the time it was deemed so utterly bright.

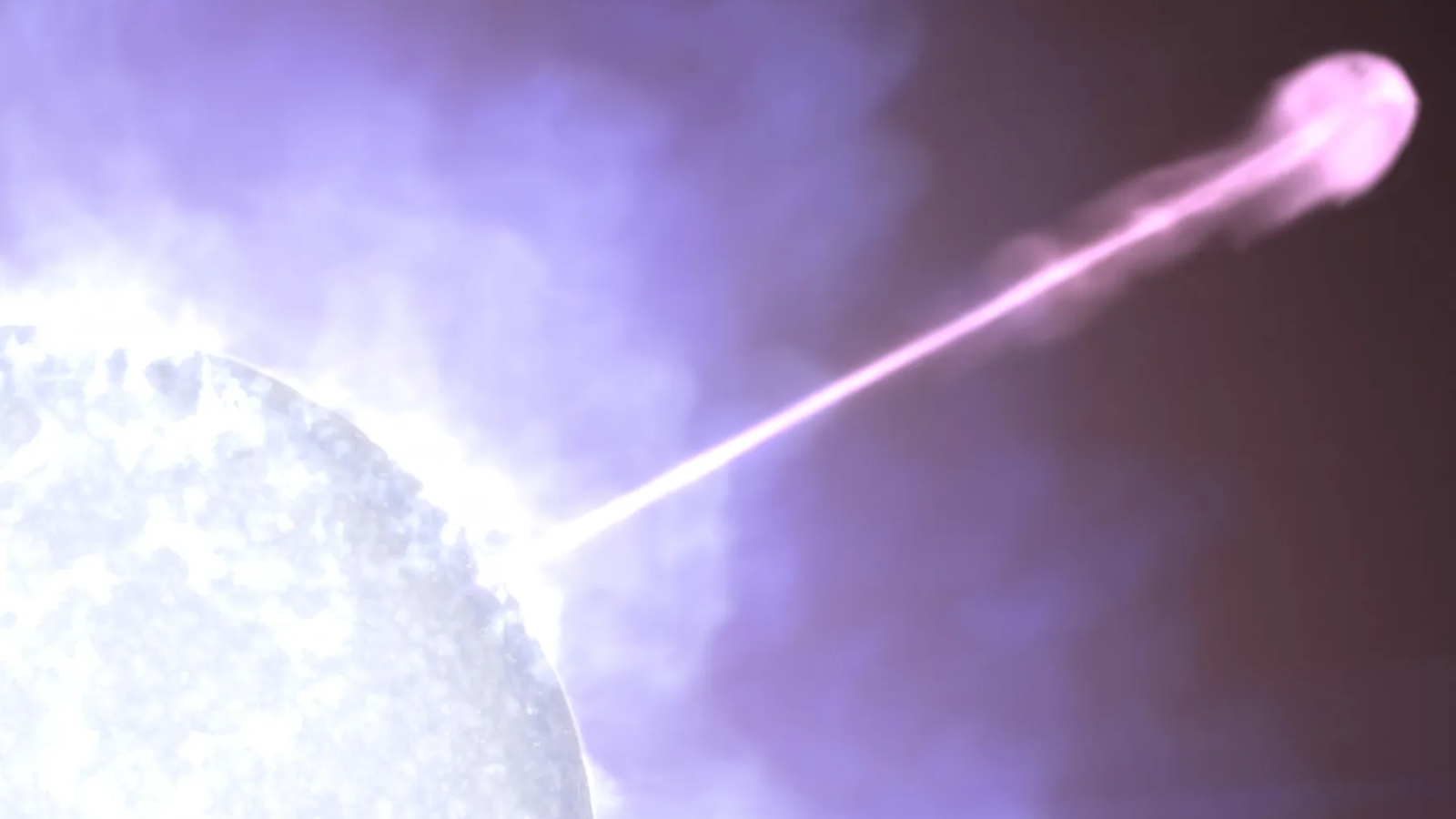

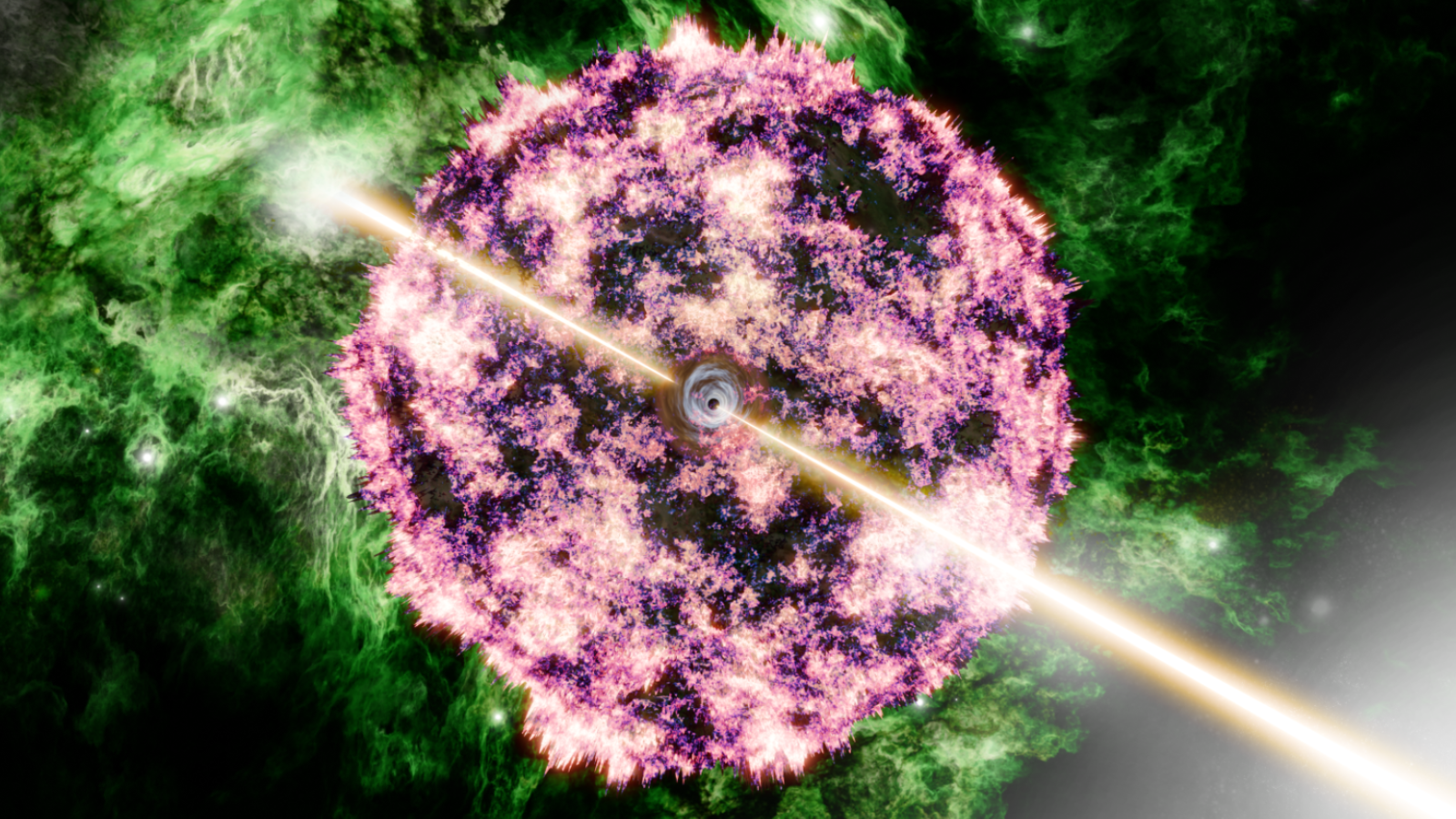

Scientists theorize the BOAT was launched by a supernova explosion that accompanied the death and collapse of a massive star located around 2.4 million light-years away from us. This event likely left a black hole in its wake.

Related: Scientists identify origin of the 'BOAT' — the brightest cosmic blast of all time

"A few minutes after the BOAT erupted, Fermi's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor recorded an unusual energy peak that caught our attention," research leader Maria Edvige Ravasio from Radboud University said in a statement. "When I first saw that signal, it gave me goosebumps. Our analysis since then shows it to be the first high-confidence emission line ever seen in 50 years of studying GRBs."

What did Fermi find in the BOAT?

The first gamma-ray burst was seen in 1967 by the U.S. Vela satellites; it was officially documented two years later, then revealed to the public in 1973.

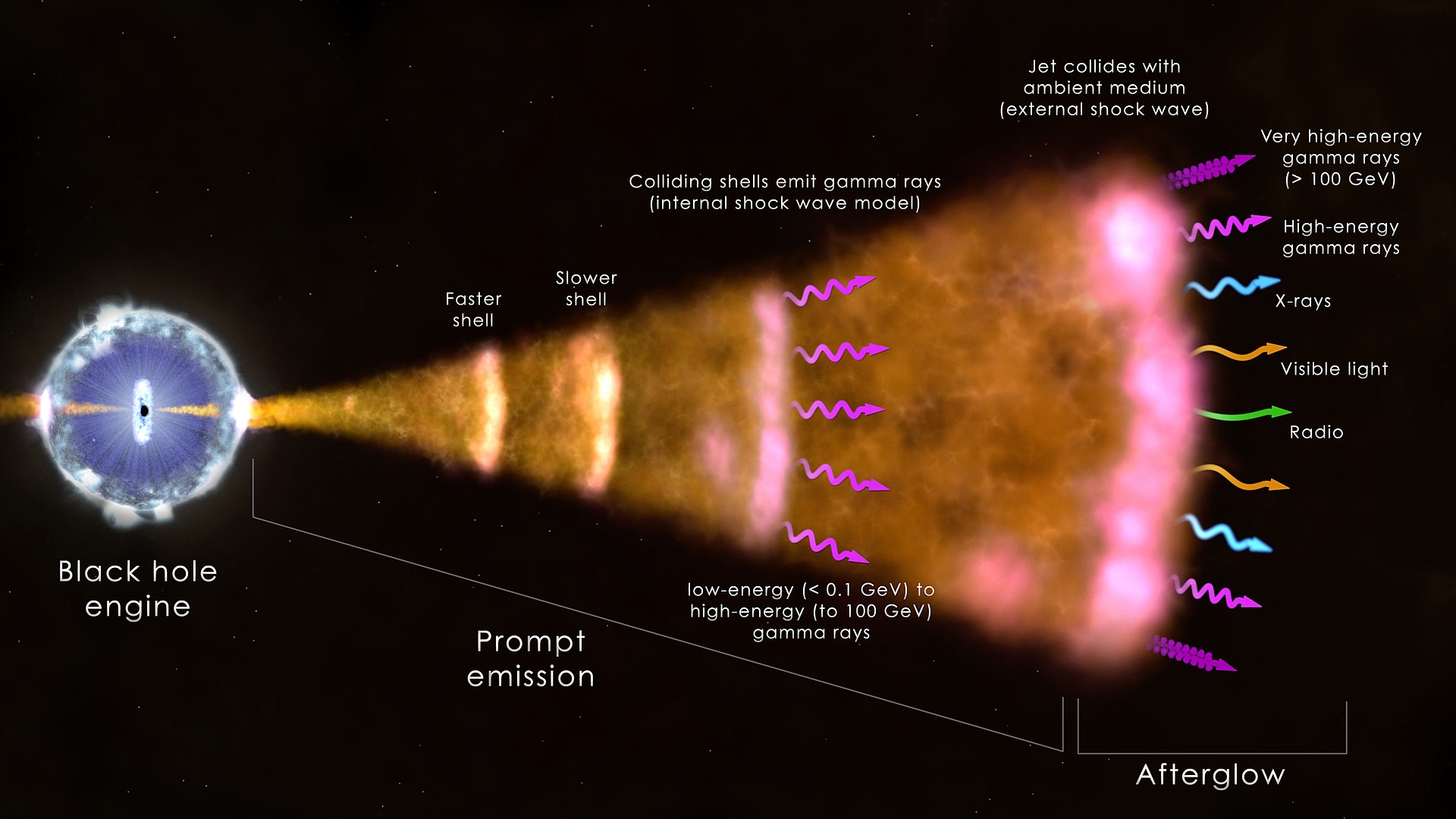

Since then, scientists have detected a plethora of GRBs, determining these brief flashes of light have cosmic origins and are the most powerful and violent explosions in the known universe. The most common type of GRB occurs when stars with at least eight times the mass of the sun run out of fuel needed for nuclear fusion in their cores and are no longer able to counteract the inward push of their own gravity; their cores thus collapse. This creates a spinning black hole that channels matter to its poles, blasting it out as jets traveling near the speed of light.

When these jets are pointed directly at Earth, we see them as a GRB.

GRBs are so powerful that if one erupted within a few thousand light-years of Earth, it could wipe out life on our planet by disrupting or destroying the atmosphere. However, even among all of these terrifying events, the BOAT almost immediately stood out.

Scientists eventually determined, using statistics regarding other observed GRBs, that an event as powerful and bright as the BOAT would be visible in the sky over Earth just once every 10,000 years. They also found, despite happening 2.4 billion light-years away, the BOAT indeed had an impact on Earth's atmosphere.

On Oct. 9, 2022, high-energy gamma-ray light from the BOAT saturated most of the gamma-ray detectors in orbit, including those onboard Fermi. This actually prevented the blast's true power from being measured at the most intense point of its duration. However, around five minutes after the BOAT was detected, it dimmed enough to allow Fermi to see it again. The NASA gamma-ray telescope saw a curious feature in its light, or "spectra," called a "putative emission line."

When light passes through matter, because elements absorb and emit light at specific frequencies, they leave absorption and emission "fingerprints" on this light. This means scientists can reconstruct the elements this light passed through and determine the chemical compositions of objects it has interacted with.

"While some previous studies have reported possible evidence for absorption and emission features in other GRBs, subsequent scrutiny revealed that all of these could just be statistical fluctuations. What we see in the BOAT is different," team member Om Sharan Salafia of the INAF-Brera Observatory in Milan, said in the statement. "We've determined that the odds this feature is just a noise fluctuation are less than one chance in half a billion."

The emission line seen by Fermi in the light from the BOAT lasted for about 40 seconds, reaching a peak energy of 12 million electron volts (MeV). The energy of light in the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum is between two and three electron volts (eV).

The researchers think they know what caused this feature. Every matter particle has an an antimatter particle "twin." When these particles meet, they annihilate, releasing their energy back to the universe. It's possible the spectral feature the team saw in the BOAT comes from electrons and their antimatter equivalents, positrons, annihilating.

"When an electron and a positron collide, they annihilate, producing a pair of gamma rays with an energy of 0.511 MeV," team member Gor Oganesyan from the Gran Sasso Science Institute said in the statement. "Because we're looking into the jet, where matter is moving at near light speed, this emission becomes greatly blueshifted and pushed toward much higher energies."

If the team is right, the particles must have been traveling at around 99.9% of the speed of light before they annihilated each other.

"After decades of studying these incredible cosmic explosions, we still don’t understand the details of how these jets work," team member Elizabeth Hays, the Fermi project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center said in the statement. "Finding clues like this remarkable."

The team's research was published on Friday (July 26) published in the journal Science.