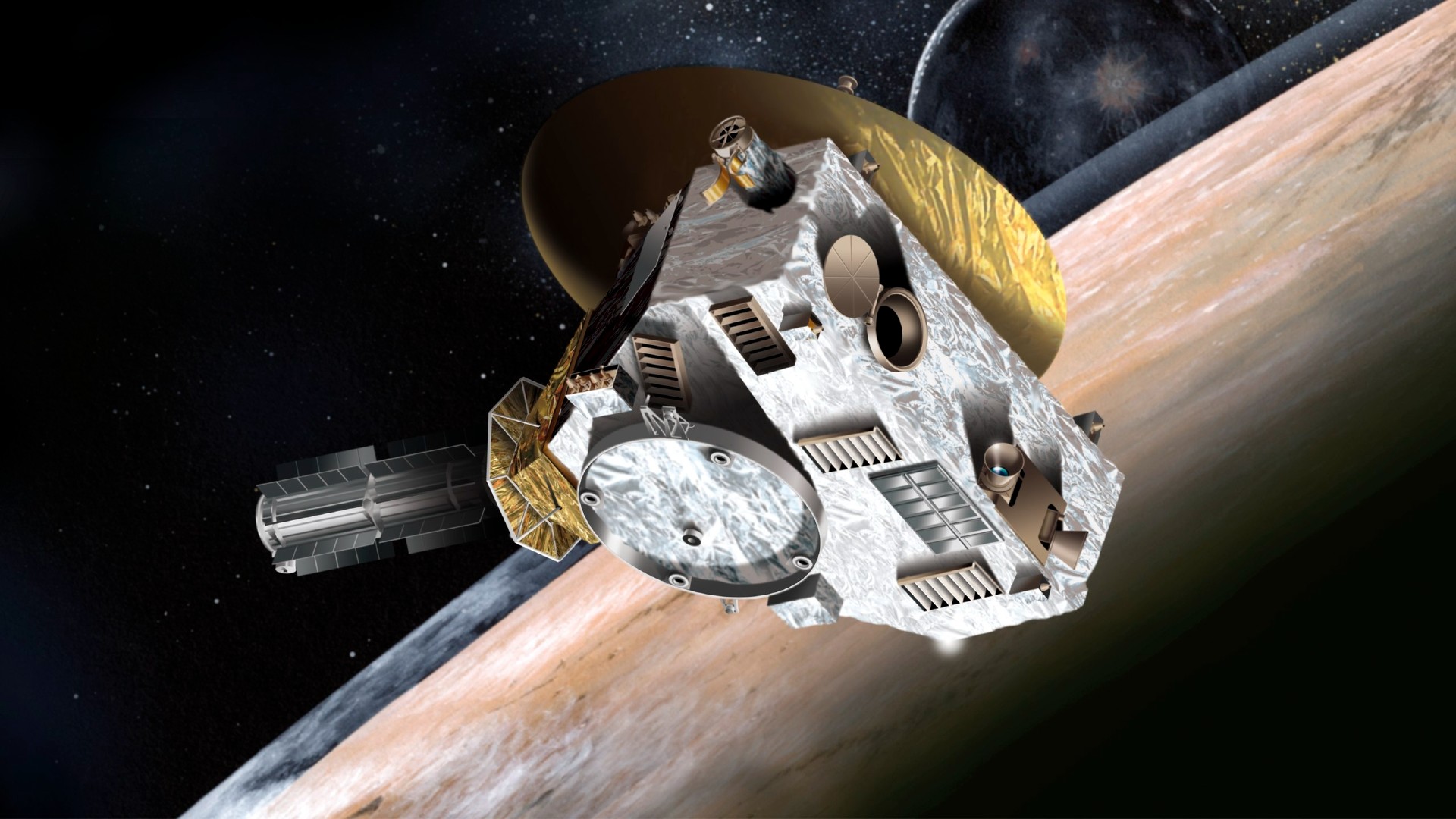

The future of NASA's New Horizons Pluto probe is uncertain following debates at NASA over how best to use the spacecraft.

New Horizons launched in 2006, and conducted a flyby of Pluto in 2015, which gave humanity the clearest images of the dwarf planet to date. In 2019, in the far stretches of the solar system beyond Pluto, New Horizons was able to observe a Kuiper Belt object (KBO) known as Arrokoth, the most distant object ever explored by humans.

Now, the probe's future beyond the end of 2024 is being called into question as NASA decides whether to keep the probe focused on its original mission or shift it to another scientific mission altogether.

Related: New Horizons: Exploring Pluto and Beyond

The controversy surrounding NASA's New Horizons probe boiled to the surface on May 4 at a meeting of the Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) in Laurel, Maryland, according to SpacePolicyOnline.com editor Marcia Smith who published notes from the meeting on Twitter.

The gathering included New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, who expressed bewilderment over NASA's decision to approve only two of the three-years proposed for the spacecraft's second extended mission. Stern says his team suggested a cross-disciplinary approach to New Horizons' remaining time in the Kuiper Belt (KB), distributed between NASA's planetary science, astrophysics and heliophysics divisions. (Heliophysics is a branch of astronomy devoted to studying the sun and its influence on the rest of the solar system.)

Instead of remaining in NASA's planetary science division, the mission will have to compete in a separate senior review for the heliophysics division beginning in 2025. Stern called decision is "shortsighted," arguing that a shift in New Horizons' focus to heliospheric science could sacrifice the study of new KBOs.

A slide Stern shared as part of his presentation reads that the shift "also goes directly against the Decadal Survey that sent New Horizons to the KB, quoting: Its 'value increases as it observes more KBOs and investigates the diversity of their properties.'" He also stressed New Horizons' favorable Planetary Senior Review results, which cited 23 "major strengths" and only 1 "major weakness."

Curt Niebur, lead scientist for flight programs in the planetary science division, also attended the OPAG meeting. According to Smith, Niebur pointed out that NASA's decision was based on the Senior Review, which also concluded the probability of another KBO flyby to be improbable, calling it a "needle-in-a-haystack" issue. The return on planetary science research from New Horizons, NASA concluded, is far less than the astrophysics and heliophysics investigations the spacecraft can accomplish moving forward.

In a separate tweet, Smith described the interaction between Stern and Niebur as "heated".

Through his frustration, Stern also made it clear that this wasn't an end to New Horizons outright. "NASA is not planning to turn the spacecraft off, simply to terminate the planetary mission and to dismiss the planetary team," Stern said. And on that, the two agreed. Niebur stated turning off New Horizons was never part of the Senior Review recommendation, and that the agency is looking for the best path forward for the spacecraft.

Traveling at over 36,000 mph (57,936 km/h), and covering more than 300 million miles per year, New Horizons won't exceed the vastness of the Kuiper Belt until 2028.