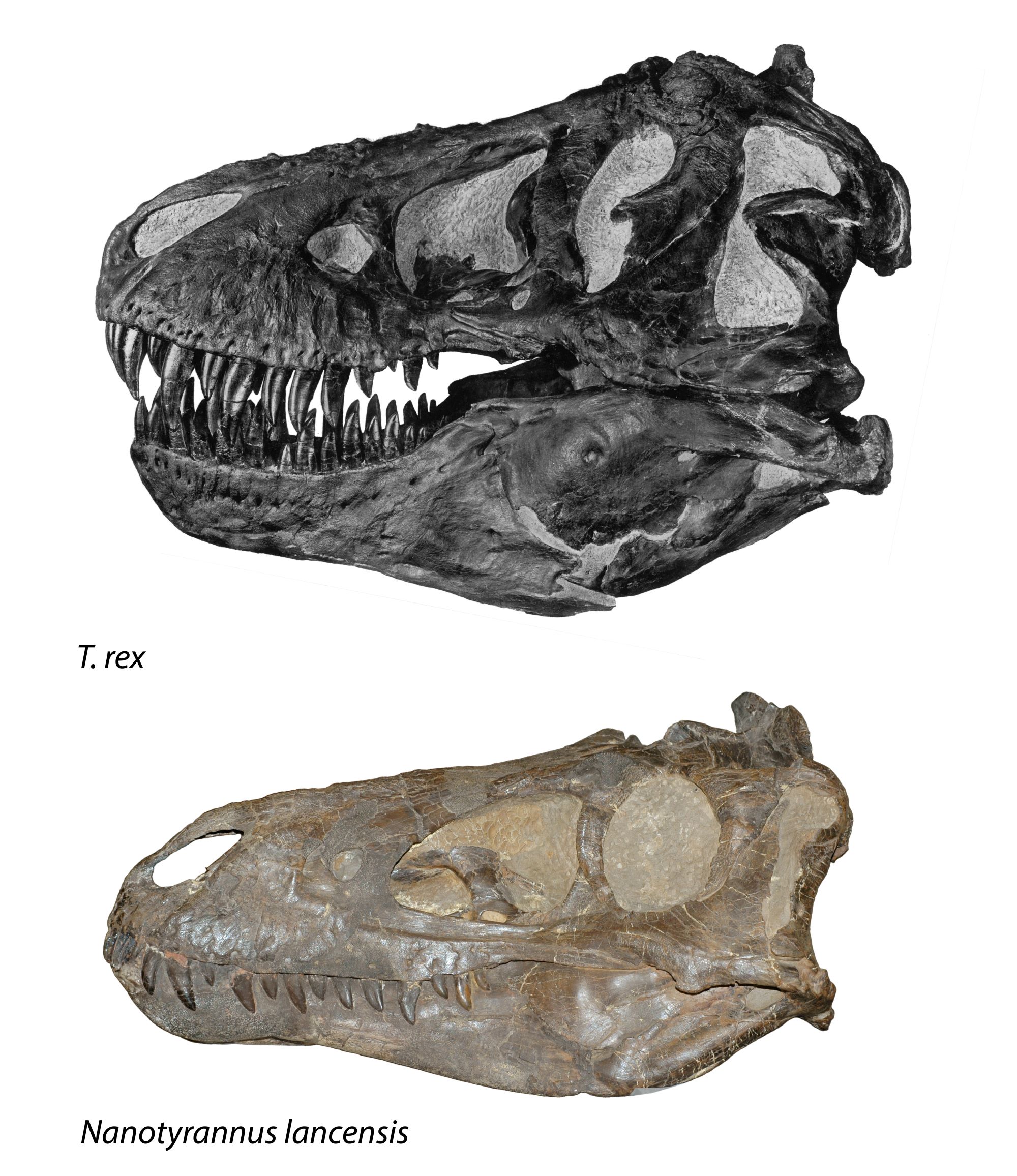

In the latest episode of a long-standing debate over the identity of a set of dinosaur fossils, a controversial new study has found that the dino bones belong not to a young Tyrannosaurus rex but to a separate species: Nanotyrannus lancensis.

In the decades since the first skull was discovered in Montana in 1942, paleontologists have gone back and forth on whether the skull and later fossil discoveries belong to a distinct species or to juvenile T. rexes.

The authors of the new study, published Wednesday (Jan. 3) in the journal Fossil Studies, claim to have snuffed out the baby T. rex hypothesis once and for all — although other experts aren't convinced.

"I was very skeptical about Nanotyrannus myself until about six years ago when I took a close look at the fossils and was surprised to realize we'd gotten it wrong all these years," lead author Nicholas Longrich, a paleontologist and senior lecturer at the University of Bath in the U.K., said in a statement. "When I saw these results I was pretty blown away."

Longrich and co-author Evan Saitta, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago and research associate at Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, measured growth rings on the fossils and found they were closely packed towards the outside of the bone. This pattern is inconsistent with the rapid growth of a young dinosaur and suggests growth was slowing and the dinosaur was reaching its full size when it died.

Related: 1.7 billion Tyrannosaurus rexes walked the Earth before going extinct, new study estimates

"If they were young T. rex they should be growing like crazy, putting on hundreds of kilograms a year," Longrich said. When the researchers modeled the growth of the fossils, they found that the dinosaur would have reached just 15% the size of a mature T. rex, weighing around 2,000 to 3,300 pounds (900 to 1,500 kilograms) and measuring 16 feet (5 meters) long. In comparison, an adult T. rex was about 17,600 pounds (8,000 kg) and stretched 30 feet (9 m) in length.

The researchers also reconstructed the dinosaur's anatomy and found it shared no distinctive features with an adult T. rex — which it likely would have done if it was a young T. rex, "in the same way that kittens look like cats and puppies look like dogs," Longrich said. "It could be growing in a way that's completely unlike any other tyrannosaur, or any dinosaur — but it's more likely it's just not a T. rex."

The reconstruction also didn't match other fossils of a young T. rex that did share features with adult T. rexes, the researchers said. Unlike T. rex, the dinosaur had a light build, long limbs and large arms that would have been "pretty formidable weapons," Longrich said. "It's really just a completely different animal," he added.

But other experts aren't backing the idea that the fossils belong to Nanotyrannus. "The article doesn't settle the question at all," Thomas Carr, a vertebrate paleontologist and an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin, told Live Science in an email. "The authors don't seem to have a solid grasp on growth variation in tyrannosaurs."

In 2020, Carr found more than 1,800 differences between juvenile and adult T. rexes — considerably more than the over 150 differences emphasized in the new study, he said. "We should expect that magnitude of differences between juveniles and adults," he added.

Opponents to the Nanotyrannus theory say the skulls of these dinosaurs have unique features only seen in T. rex — including a wide forehead and narrow snout, Carr previously told Live Science.

Thomas Holtz, a principal lecturer in vertebrate paleontology at the University of Maryland, is also skeptical. "Ultimately, the key fossils needed to settle this — fully adult Nanotyrannus that are not Tyrannosaurus, or 11 [to] 13 year old Tyrannosaurus that are definitely not Nanotyrannus — haven't been discovered," he told Live Science in an email.

And so the saga continues, said David Hone, a paleontologist and reader in zoology at Queen Mary University of London. "There's a bunch of old ideas resurfacing [in the new study] that aren't any more convincing than they were before, and there's some new ideas which mostly aren't very convincing either," Hone told Live Science in an email.

Currently, only T. rex is recognized in the Tyrannosaurus genus, but Hone suggested Nanotyrannus or another set of fossils could prove to be a second, closely related species in the genus. He and other paleontologists are "happy with the idea that there might be more than one species," Hone said. "It is odd in some ways that Tyrannosaurus is apparently a uniquely large predator in its ecosystem," he said.

The discovery of a second species in the genus "might fill some gaps and explain away some inconsistencies," he added. "But that was always going to have to be with some really convincing arguments that overturn a lot of ideas and data that people have been building for years, even decades."

Editor's note: This article was updated at 9:50 a.m. EST on Jan. 4 to correct the estimated lengths of the tyrannosaurs.