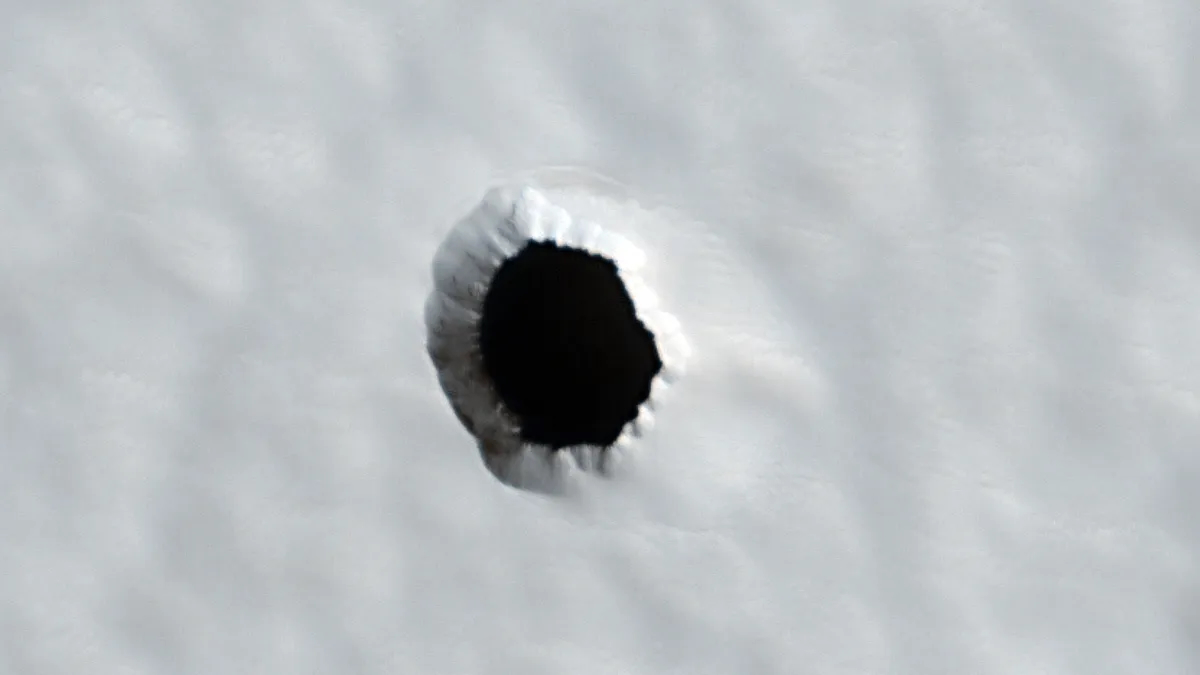

A mysterious pit on the flank of an ancient volcano on Mars has generated excitement recently because of what it could reveal beneath the surface of the Red Planet. Here's what that means.

First things first, the pit, which is only a few meters across, was actually imaged on Aug. 15, 2022 by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which was about 159 miles (256 kilometers) above the Martian surface at the time. This hole in the ground is also not alone. It's one of many seen on the flanks of a trio of large volcanoes in the Tharsis region of Mars. This particular pit is found on a lava flow on the extinct volcano Arsia Mons, and appears to be a vertical shaft. That raises a question: Is it just a narrow pit, or does it lead to a much larger and remarkable cavern? Or, could it perhaps be a really deep lava tube formed underground long ago when the volcano was still active?

Related: Will future colonists on the moon and Mars develop new accents?

There are several reasons why pits and caves on Mars are of interest. For one, they could provide shelter for astronauts in the future; because Mars has a thin atmosphere and lacks a global magnetic field, it cannot ward off radiation from space the way that Earth does. Consequently, radiation exposure on the Martian surface averages between 40 and 50 times greater than on Earth.

The other enticing aspect of these pits is they might not just provide shelter for human astronauts; they could hold astrobiological interest in the sense that they could have been sheltered abodes for Martian life in the past — perhaps even today, if microbial life indeed exists there.

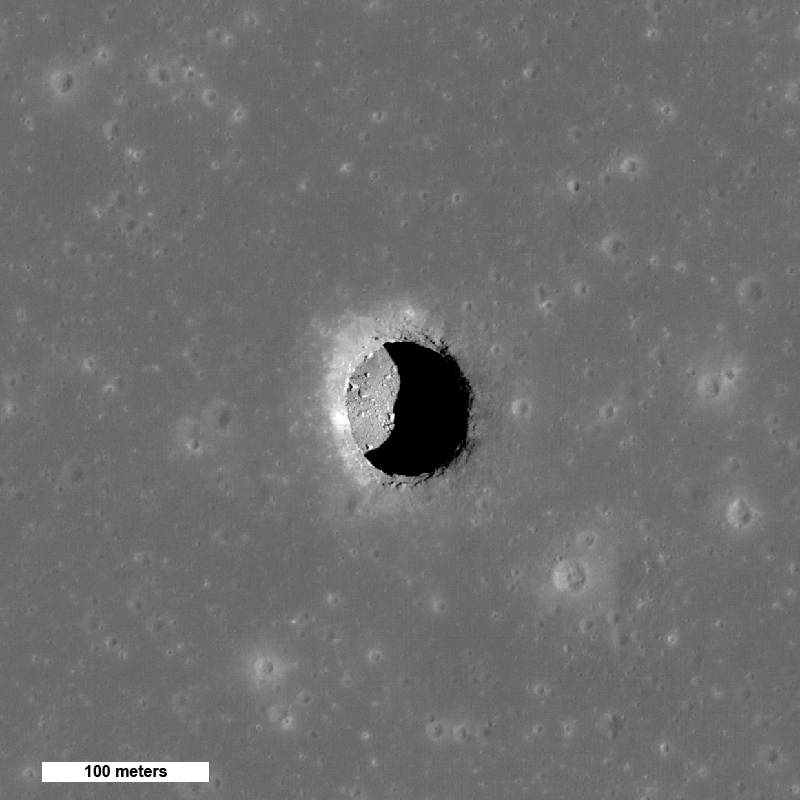

The presence of these so-called holes on the flanks of volcanoes is a big clue that they are probably connected to volcanic activity on Mars. Channels of lava can flow away from a volcano underground; when the volcano grows extinct, the channel empties. That leaves behind a long, underground tube. We see such tubes not only on Mars, but also on the moon and on Earth.

Sometimes, if the crust is thin enough, the ceiling of these tubes collapses. If a collapse happens along the tube's entire length, it forms a feature called a rille, which is a long trench commonly found on the moon and sometimes in other areas of Mars. If the tube's ceiling just collapses in small areas, however, we get pits like those imaged on Arsia Mons. Planetary scientists have also seen pit chains on the flanks of Martian volcanoes, which are linear stretches of multiple pits seemingly following the length of a lava tube.

How deep these pits descend is a mystery, however, and it remains uncertain whether the pits open into a large cavern or whether they are contained to a small, cylindrical depression. Some Martian pits have been imaged when the sun is high enough in the sky to illuminate what appears to be the sides of the pit wall, which implies they are shafts that go straight down into the flank of the volcano. This would seem to suggest these pits are unlikely to open into larger caves or tubes. If so, this would make them similar to pit craters found on the volcanic mountains of Hawaii, which also don't open up to anything larger and which are produced by the collapse of material deeper underground, which causes material above to sink.

However, pits on the moon have been shown to have boulder-strewn floors that appear as though they could lead to a larger subterranean volume.

Pits can also be formed through tectonic stresses that fracture a world's surface, and these may be less likely to lead to a larger cavern. And finally, one other — possibly less likely — explanation is that these pits open up into where underground rivers once flowed billions of years ago.

We can see a similar phenomenon on Earth, in the form of a geological feature called a karst, which forms when limestone bedrock dissolves and weakens, creating pits and sinkholes that open up into areas of groundwater. If that is the case on Mars, then, if the Red Planet ever once had life, those organisms may have sheltered in karsts. Indeed, running water down the flank of an active volcano would have been warm, providing the perfect protected environment for life to flourish and stay safe.

Still, this is all speculation for now. We'll only have some concrete answers after future missions actually explore some of these pits. Though a rover that drives to the edge of a pit would be unable to descend, an airborne mission along the same lines as NASA's Ingenuity helicopter, which operated on Mars for three years before it became grounded in January 2024 after damaging one of its rotor blades, would have the ability to hover over and descend into a pit to see what is down there.

If these pits do open up into caves, they may become a preferred landing site for future crewed missions to Mars that will require astronauts to build a sheltered basecamp away from the world's unrelenting radiation.

Originally posted on Space.com.