Myles Garrett had a dream five months ago. He has a lot of those, hundreds of dreams that descend nightly, random and pointed and pointless and inspirational and pure fantasy. Garrett remembers his dreams, too, which makes him a High Dream Recaller. HDRs, research says, display higher brain activity, tend to daydream and enjoy fantasy worlds, are creative and more open to experiences. That’s him. Myles Garrett, The Dreamer.

This dream: He’s outside a hotel where he has never stayed, in a beautiful, wintry landscape; his girlfriend, snowboarder Chloe Kim, two-time Olympic gold medalist, is talking to him, but standing in front of him, her back turned.

Garrett describes this in Los Angeles on Jan. 20. He’s less than 48 hours removed from a flight from Switzerland to LAX. And he’s describing how the moment in that dream, which he hadn’t considered since the morning after, had happened IRL three or four days earlier, exactly as envisioned.

“I [get] déjà vu a whole bunch,” he says. “Or, I guess, I [dreamed] it, and it’s hard for me to recall that moment. Until it happens.”

On the night of Jan. 3, the Browns’ defensive end nodded off in Cincinnati, on the eve of the final game of the season. He was sitting on 22 sacks, a half sack behind the NFL single-season record since the stat was officially recognized four decades ago. Another one and he’d have more than any pass rusher ever to lock eyes on a quarterback and grunt like it’s time for dinner.

His dream that night: Garrett is on the field, chasing Bengals QB Joe Burrow and the record. Not just for himself, but also for his teammates, the Cleveland D-line room, defensive coordinator Jim Schwartz, his parents, siblings, Kim. But he cannot get that elusive No. 23. Play after play, amid double teams and triple teams and chip blocks, he comes close but never can quite corral Burrow.

Just before Garrett woke up on a day he would remember forever, his subconscious flashed a dream montage. This tableau was failure, disappointment. And not just failure but how it felt to fail, with the world watching, while on the precipice of a record that is among the NFL’s most hallowed.

The last thing Garrett recalls from that dream is an image: him, sitting on his couch alone, watching news clips about the mark he almost broke. “I remember a sense of, like, dread, in my chest and stomach,” Garrett says. “This was the last opportunity. And I let myself down, I let my family and my friends down, knowing that this was a moment I hoped to share with everyone.”

Then he woke up.

“There’s no way,” Garrett promised himself. No way he’d let that happen.

Michael Strahan assumed the single-season sack throne 24 seasons ago. Nothing like it, he says, even now.

Strahan—a co-anchor of Good Morning America, an analyst on Fox NFL Sunday and the host of The $100,000 Pyramid—has become America’s uncle since his retirement in 2008, ubiquitous and beloved. But he says nary a day has passed without someone reminding him of that 2001 season and his 22 ½ sacks. Strangers mention it more often than his Super Bowl XLII triumph with the Giants. “It’s cool, man, honestly; a really cool record to have,” Strahan says.

He’s on the phone from New York, and the elation in his voice isn’t the result of modern media supremacy. It’s for the new Sack King, his mentee, who refers to Strahan as Big Unc. “[The mark] doesn’t define your career,” Strahan says. “But it puts a nice little stamp on [it]: ‘I’ve done something that no one else has ever done in a game that has so much history.’ ”

Elite pass rushers debate this record more than anyone. Sacks arrived late to the NFL’s numerical bonanza; they weren’t officially counted until 1982. Strahan considered Deacon Jones, who retired in 1974 and is third on the unofficial career list (173 ½), his mentor. Strahan knew Lawrence Taylor and Bruce Smith, too.

Jones once told Strahan he had 100 sacks in one year and insisted that he, Deacon Jones, was the real all-time sack leader and not Smith, who retired in 2003 with 200. This debate among retired pass rushers confirmed Strahan’s already firm opinion. That this record, for any defender, is “the most prominent anybody wants.”

He cackles as he jokes about tackles, the vast majority of which are instantly forgotten, and interceptions, which carry the same impact but not often the same pizzazz. Sacks are sexy. Sacks are powerful. Sacks are art. Sacks are science. Sacks are violent. Sacks demand celebrations. Pass rushers are almost always dreamers. How else could anyone handle the job, its many hazards and its many disappointments? Each sack is like a goal in a tightly contested World Cup final, elation possible on any play, but rare, the product of dozens of failed attempts. And that willingness—or delusion—embedded in these chasers to fail and fail and fail and still rush and rush and rush.

“It’s so freaking hard, man,” Strahan says. “It’s every play. Every play, as if it’s your last play on Earth.”

On the morning of Jan. 4, Garrett didn’t tell anyone about his dream. Giving voice to it struck Garrett like putting it into the universe. Instead, he sent one text to a fellow Browns defensive lineman. It wasn’t written in all caps but dripped with the same urgency.

Get ready.

The first half against the Bengals wasn’t like the dream; it was the dream. Play after play, there was Burrow, close but never close enough.

At halftime, the overthinking started. Garrett wanted history so badly that the very act of seeking this history had infiltrated his mind and grown into, his words, fear and anxiety. “Then that doubt creeps in,” Garrett says.

He acknowledged the doubt, understood where it came from and clocked back in. In L.A., looking back, Garrett admits that some of his dreams are “night terrors and even more horrific.” He’s writing a story about those that will become a graphic novel.

Two quarters remained.

Garrett wasn’t supposed to do any of this, really. If greatness lurked in his DNA, his body once hid it well. Growing up in Arlington, Texas, he was the antithesis of what he would become: undersized, tall and skinny with flat feet. He had surgery on both feet in his youth, surgeons building out arches and releasing tension in the tightest of his tendons with a small incision. This stoked his insecurities, which led to body-image issues, which further stoked his insecurities.

Football transformed him. When he stepped onto the field, everything, Garrett says, “just sheds off and that guy that y’all see is just … super amazing.”

There’s a process for this transformation. On the nights before games, Garrett, now a 6' 4", 272-pound behemoth, prefers watching Godzilla movies. Then he pictures himself destroying whatever hapless offense happens to be up next. “Like Godzilla destroys cities or monsters,” he says.

The best offensive linemen draw him further into character. Garrett envisions those individual matchups as similar to heavyweight kaiju bouts, immense in scale, epic and destructive. Like Mega Kaiju, from Pacific Rim Uprising, where three of the most powerful Kaiju combine into one triple-hybrid monster. The Mega Kaiju is said to redefine destructive potential.

Kind of like Myles Garrett.

Last offseason forced Garrett to plumb the depths of his football soul. Everywhere he went, strangers told him he deserved better than the Browns had given him, that his dominance needed to be showcased—and to be fully showcased, he needed wins as well as sacks.

The city of Cleveland means more to him than Garrett can properly express. He wanted to return, to win, in Cleveland, for Cleveland. But it didn’t take his intimate knowledge of the Browns’ organization to wonder if that might be possible.

While his agent, Nicole Lynn, negotiated with decision-makers, Garrett vacillated between options. At one point, a trade was requested. The Browns insisted they’d never trade him. They demonstrated that commitment with a contract extension last March that at the time made Garrett the highest-paid defensive player in NFL history, with more than $123 million guaranteed. “I feel like I got what I earned, and that was the market I had set from the level of consistency I had displayed,” he says. “I wasn’t trying to hit them over the head. And I wanted something that would still structure in a way in which we could bring in talent and try to win.”

I asked him about something I’d heard back in April: That he had taken less money to stay in Cleveland. Yes, he confirmed, that’s true. No, he didn’t feel it necessary to shoot down the most common sentiment attached to his historic season, that he stayed for the money and cared, primarily, about his statistics. “If I would have left, they would have said I was ring chasing,” he says. “If I stay, they say I stayed for the money.”

He had larger issues to address before the season even started. Like a shortened offseason thanks to another surgery—two, actually, one on each foot. The pain in each never went away. Throughout his football career his feet have become inflamed, making each step so painful that Garrett limped through the 2024 season after considering not playing at all. He started every week, adding 14 sacks and a career-high 22 tackles for loss while making first-team All-Pro. Again.

After the procedures Garrett felt “immediate relief.” During joint practices with Philadelphia in August he went full out, each rep, sometimes irritating his opposition. He wanted to scrap with stud left tackle Jordan Mailata in a meaningless, informal heavyweight kaiju bout. “I just don’t get the opportunities, regardless of how great the tackles are,” Garrett says, sounding wistful, almost, of a scrimmage that redefined his destructive potential for 2025. “I mean, [the Eagles] have some special [tackles]. [And] I can beat anyone one-on-one.”

After that practice, Mailata told reporters that Garrett sometimes presented as impossible to block. He would start in a four-point stance but maintain it for four or five yards, while moving at speeds humans his size simply never dream of. Mailata asked: What was he supposed to do? Fall on top of Garrett, who might just lift and carry his 6' 8" frame into the quarterback?

“I don’t think that would work,” Garrett says, his smile sly and telling.

“You know what I love about him?” Strahan asks. “He’s everything that you think an athlete probably isn’t.”

Strahan is speaking directly to Garrett’s many interests, that elite functional connectivity. Critics, Strahan says, often twist the wide totality of Garrett’s passions into sentiments both disdain. That he doesn’t love football. That he cares about individual statistics more than Cleveland’s record. “Which,” Strahan says, “is completely wrong.

“I don’t think people understand just how awesome he is. Because they really haven’t gotten a chance to know him, because his teams haven’t had the success or the spotlight to highlight him more.”

Watching Garrett play can unspool like a dream sequence. Start with his size. Or, as Strahan puts it, “massive, like I don’t know what Mama was doing with that breast milk!” To stand that tall, stretch that wide, be that thick—and still run like a cheetah—doesn’t seem fair. Add the flexibility that Mailata highlighted, the basketball backboards Garrett has shattered, the times he has leaped over blockers. This nerd, the skinny kid born flat-footed, is now a specimen.

He’s versatile. Garrett rushes from either edge, from inside as a defensive tackle, or standing up like a linebacker.

He’s not reliant on one move. Garrett utilizes speed, power, hand swipes, spins, dip and rips, butt and jerks, a football Euro step, even a technique that looks like he’s dribbling a basketball through his legs.

He’s complete, especially this past season, his best year yet in stopping the run.

He’s dominant but not an exact comparison to those who sacked before. “He does everything, and that’s what’s mind-blowing,” Strahan says. “Power, speed, changing direction, agility, his ability to lean on a rift, moving like he’s right off the ground; his ability to come inside, open at the hips, all these things that you’re limited, usually, in only being to do one or two. He does what Reggie White did. He does what Bruce Smith did. He does what I did. The one thing we became known for, he does. And there’s not one thing he’s known for. Because he can do it all.”

Most weeks, that’s the gig. Do it all. His titanic clashes aren’t typically one-on-one. “I might be the most double-teamed player ever,” the new Sack King says. “I don’t think anyone else has seen the kinds of packages and protections I’ve seen.”

Some teams, he says, shift the offensive line in his direction. He’ll meet a guard and a tackle, with a tight end behind them, ready to leak out, or a running back, ready to chip away. In the most extreme version of this calculus, he’ll face a guard, a tackle, a tight end and a back. This diet of triple and quadruple teams began increasing about five seasons ago, he says.

As for direct, rare, mano a mano, Garrett estimates he gets three or four of those each game. When only one blocker stands between him and the quarterback, he guesses the offense will run a fake or assumes they have something quick planned, like a screen. Sometimes, when the opportunity arises, he’ll think things like, “You can’t be serious. You haven’t given this to me all day.”

Inside the Browns’ defensive line meeting room, the number on the whiteboard reminded Garrett and his teammates of their shared ambition. Garrett had said before the season he wanted 24 sacks. After two games—and 3 ½ of those—he upped it to 25, which he scribbled on the whiteboard and his wrist tape.

Garrett added half a sack in the Browns’ first win (Green Bay, Week 3), then went sackless for three weeks. This “drought” didn’t raise any internal alarms. He sprained his left ankle in the third or fourth quarter of Week 4 in Detroit. No sacks didn’t equate to abort plan.

He snapped the drought against Miami but still didn’t feel like himself. He went to his coaches. He wanted more practice reps—like, all of them. “I didn’t like how I’d been playing,” he says now. “I wanted to knock the rust out and make sure I was healthy and back to [my] standard.”

In Week 8, at New England, Garrett doubled his season sack total in one game. Down went Drake Maye on the Patriots’ first possession. Garrett registered five sacks against the Patriots, breaking his own Browns’ single-game record.

Garrett’s only comparison for this spree dated back to high school. He played against a team that featured a friend—they’d competed in track together—at quarterback. He dropped his friend nine times, his dominance so complete, so thorough, that Garrett has apologized to him for years. “He was sick,” Garrett says, “because he also knew they would have to see me in their basketball season.”

He never forgot what wideout Odell Beckham Jr. told him back in 2021: “There [are] four quarters—who says you can’t get a sack in every [one of them]?”

One more sack, the next week, against the Jets.

Four sacks against the Ravens.

Three more against the Raiders.

Garrett had 18 sacks at that point. Collecting 14 in one five-game stretch marked an NFL first.

He still had six games remaining.

In the final weeks of 2025, Garrett implored everyone around him to remain calm, stay composed. “I’m chasing this thing that every other team is trying to avoid,” he says.

Which left only that finale in Cincinnati.

Through three quarters, the Bengals stymied Garrett. He touched Burrow. Bumped Burrow. Chased Burrow. He blitzed standing up, like a linebacker. He rushed from the inside.

“If you get an opportunity,” he continued to remind himself, “make the most of it.”

After halftime in Cincinnati, when the dream resurfaced, Garrett tried to shift his mindset. “I’ve already told myself it was going to happen,” he says. “That it’s a matter of time. You’re going to get one. You’re due.”

That’s all he needed—one play, one rush—and he delivered in the fourth quarter. Cleveland led, 17–12. On a first down at the Browns’ 45, Garrett timed the snap so well he almost jumped offside. His get-off on this play: 0.23 seconds, his single fastest jump this season per Next Gen Stats. Cincinnati tackle Orlando Brown Jr. stood between Garrett and history. Garrett swam past him like Michael Phelps, reaching Burrow before he could begin his reads. Garrett turned that corner only eight yards beyond the line of scrimmage, total time 2.3 seconds from snap to celebration, or 1.4 seconds faster than the NFL average.

He raised both arms skyward, then dropped them, then bowed. Teammates crowded around, raising him onto their shoulders, something that Garrett says he didn’t know was possible. No one had ever picked him up off the ground before. He jogged over to the stands and embraced those who matter most.

a once-in-a-lifetime talent continues to make his mark#CLEvsCIN on CBS and NFL+ pic.twitter.com/GOy951yUP9

— Cleveland Browns (@Browns) January 4, 2026

The montage that ran through Garrett’s mind was the opposite of his dream. He thought about the toiling he did in Dallas last offseason, alongside fellow elite pass rushers Micah Parsons, Will Anderson Jr. and several Cleveland teammates. He loved them all and insists there’s no record without his fellow Browns and their persistence. They fought deep into a miserable season, through injuries, minus the history and acclaim that went to Garrett.

That’s what screamed amid the celebration. Garrett wasn’t featured by himself. Those teammates implored him to step forward, take a bow, step into the spotlight all alone. They called for something grand, one of his signatures. That’s not what Garrett wanted. Nor what the record meant to him.

“I just wanted to give thanks,” he says.

TruMedia provides some necessary context. Garrett notched a sack on almost 5% of his snaps in the 2025 season, the highest rate posted by any defender with more than 500 snaps in the past five years. His average get-off of 0.711 seconds ranked first among qualified rushers. Only three of his 23 sacks came on plays where the Browns blitzed, which meant that 20 of his sacks were on non-blitz drop-backs, or four more than any other player in any other season over the last decade. He was double-teamed, meanwhile, or chip blocked, on 186 of his rushes, the NFL’s highest season tally since 2018.

Garrett became the first player since sacks were made official to record at least 12 in six straight seasons. He is also the only player with at least 10 sacks in each of the last eight seasons. He holds the record for most sacks ever, by any player, under age 30. He made first-team All-Pro as a unanimous selection.

He was a near lock to win NFL Defensive Player of the Year for the second time in three seasons, too. No defender has ever won more than three and only three players—Lawrence Taylor, J.J. Watt, Aaron Donald—have done that. Garrett only turned 30 in late December.

Garrett isn’t one of those people who says they listen to every musical genre. He actually does, his tastes ranging from Journey, Boston and Led Zeppelin to Marvin Gay, Howard Melvin & the Blue Notes, Earth, Wind & Fire and Teddy Pendergrass. Even while conducting an interview, music plays softly from the phone in his pants pocket.

Garrett has come to see pass rushers and pass rushing as the NFL’s version of karaoke. Different styles. Different voices. Like Von Miller and his ability to manipulate his body, so masterful, Garrett says, that he’s basically Luther Vandross. Garrett is versatile, like Reggie White, but not as powerful as the “best power rusher that ever played.” White was like Aretha Franklin. He boomed.

Garrett sees himself as Steve Perry, Journey’s front man at the band’s peak. He’s not as graceful as Miller, but he can finesse, smooth and cat-like. He can also rock out with the best of them. “Most guys excel at one or two things,” Garrett says, “and the truly exceptional have no fear in one thing or do multiple things at an elite level.”

What’s possible for Garrett in future seasons cannot be contained any more than him. “I still think 30 [sacks] is out there,” he says. “I still think 25 is out there next year.”

Soon, Garrett will climb above his career ranking—he’s currently tied for 20th on the official all-time list with Dwight Freeney, at 125 ½—and debates will shift from single-season records to career ones. Strahan, for one, believes Garrett can break Smith’s record.

Garrett must draw a critical delineation there. The record was awesome, a goal but not the goal, not what he wants most. Signing with the Jordan Brand in January was sweet and symmetric, given the 23 sacks. But Cleveland fired coach Kevin Stefanski after the season, signaling a new direction for the franchise. Garrett’s goals remain unchanged. He is committed to winning.

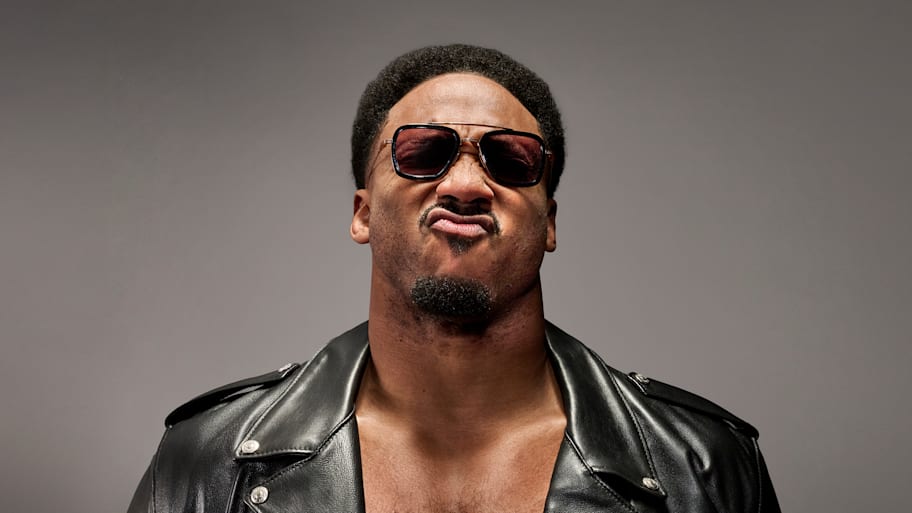

At his Sports Illustrated cover shoot, Garrett donned Terminator-style sunglasses and wore a leather jacket, with no shirt underneath. This man, born with flat feet, skinny and self-conscious, uncomfortable in social situations, a little nerdy, is now that guy. “He makes Arnold Schwarzenegger look like a little person!” Strahan says.

After the celebrations, on the day he set a new single-season sack record, Garrett played “I Wonder,” by Kanye West, as he walked into his news conference.

I’ve been waitin’ on this my whole life (And I wonder)

These dreams be wakin’ me up at night.

More NFL on Sports Illustrated

- One Move Every AFC South Team Should Make This Offseason

- One Move Every NFC South Team Should Make This Offseason

- 2026 NFL Free Agency: Five Best Safeties Available

- 2026 NFL Free Agency: 10 Best Edge Rushers Available

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Myles Garrett Relied on Big Dreams—and a Little Self-Doubt—to Become the Sack King.