Canada needs to build more homes, faster, according to a recent report by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The report estimates that British Columbia alone will need 570,000 new units by 2030 to meet a moderate affordability level of 44 per cent.

Not coincidentally, building more housing has gained steam among policy-makers, including David Eby, B.C.’s minister of housing and frontrunner candidate to replace John Horgan as NDP party leader and premier of the province.

While it’s important to recognize the lack of affordable housing as part of the housing crisis, the problem with our housing system isn’t as simple as the disequilibrium between supply and demand. Increasing market housing supply will not end the housing crisis on its own.

Drawing on a B.C.-wide survey of 1,004 residents conducted from March to April 2021, our recent study shows that unaffordability is only one type of housing vulnerability that has taken its toll on British Columbians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Market rental tenants hit hardest

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about a second pandemic of social isolation through the public health measures put in place to combat the spread of the disease.

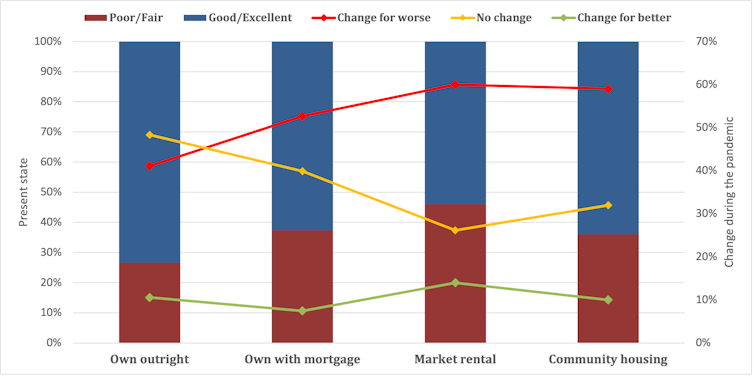

While necessary and largely effective, these restrictions took their toll on well-being: between 40 and 50 per cent of respondents reported physical and mental health declines one year into the pandemic.

However, these negative secondary effects of the pandemic did not impact everyone equally. Our study found that homeowners fared the best in mental and social well-being, while market rental tenants fared the worst.

Most surprisingly, community housing tenants (those living in subsidized, non-profit or co-op housing) reported the same level of mental well-being as those who owned a mortgage.

Community housing tenants also appeared less restricted in their social interactions — 43 per cent of this group reported reduced social interactions during the pandemic, compared to over 60 per cent of market housing tenants and homeowners with a mortgage.

The disparity in well-being outcomes demonstrates that policy that only addresses housing affordability fails to take the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic about well-being into account.

Housing vulnerability more than ‘core housing needs’

The official core housing needs indicators used to assess housing vulnerability in Canada are unaffordability, overcrowding and poor dwelling quality. We argue that Canadian housing policy needs to go beyond them.

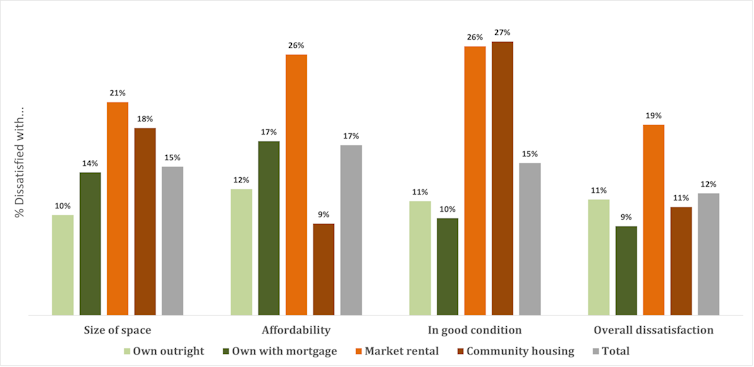

We found that market housing tenants were more likely to live in inadequate housing that was too expensive, in ill repair or inadequate in size. In comparison, only 11 per cent of community housing tenants were dissatisfied with housing adequacy, giving high ratings to housing affordability in particular.

However, our research shows the pandemic has brought to light forms of housing vulnerability beyond inadequacy, such as housing instability, the ability to stay safe and healthy at home and reduced access to neighbourhood amenities and resources.

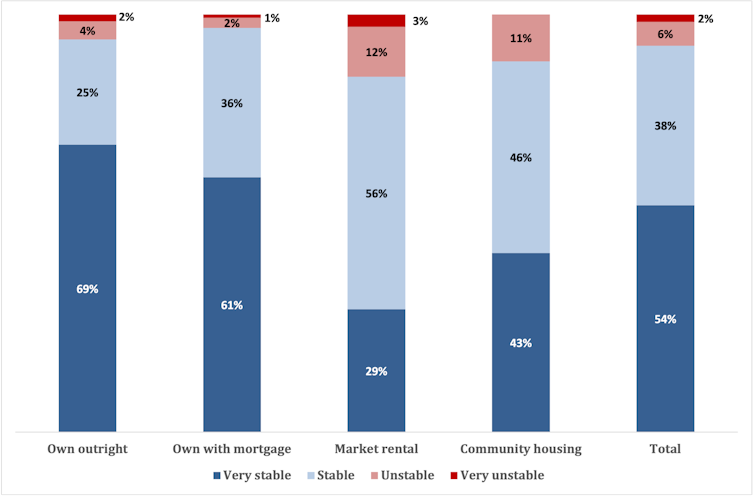

Housing instability

A small proportion of survey respondents expressed a sense of residential instability, meaning they felt they were unable to stay in their dwelling without interruptions or complications. Our study found that 15 per cent of market housing tenants experienced housing instability, compared to 11 per cent of community housing tenants.

Limited housing affordances

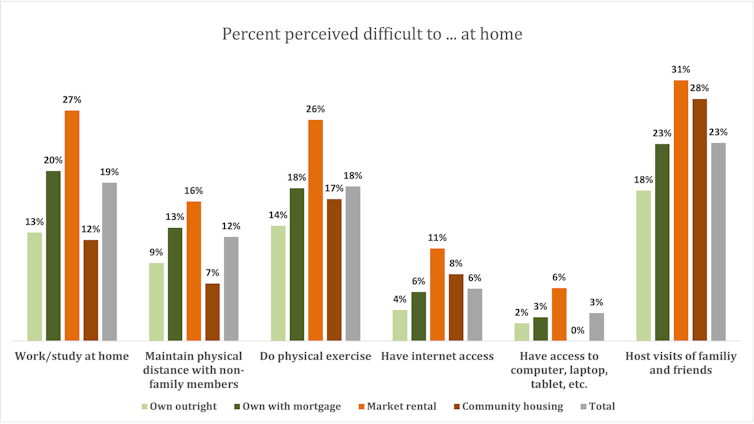

Housing affordances are housing features or functions that improve people’s everyday lives. In the context of the pandemic, this meant how dwelling spaces allowed residents to practice physical distancing and cope with secondary effects of the pandemic.

Nearly a quarter of respondents found it difficult to host occasional visits from family members and friends during the pandemic, while 19 per cent had trouble working or studying from home and 18 per cent had difficulty exercising at home. Some also reported difficulty maintaining physical distances with non-family members.

Market housing tenants faced above-average challenges in all aspects. Community housing tenants fared better, reporting less-than-average constraints for all activities except hosting visits from family and friends.

Neighbourhood inaccessibility

Neighbourhood accessibility is how satisfied respondents were with access to neighbourhood amenities and facilities, such as public transit, stores, private and public open spaces and community programs.

Most respondents were satisfied with neighborhood accessibility. Homeowners were less satisfied than renters with their access to public transit, likely due to the lack of public transit in certain parts of the province.

Both renter groups — 25 per cent of market housing and 15 per cent of community housing tenants — were unhappy with access to private outdoor spaces. This could be because access to parks and public spaces was restricted during the pandemic and more renters tend to live in apartments without balconies.

A window to better social policy

Housing vulnerability means more than the lack of affordable housing — it also means housing instability, lack of housing affordances and access to neighbourhood amenities. Renters in the private market demonstrated unexpected housing vulnerability, faring worse than community housing tenants in important ways.

It’s clear the market alone doesn’t deliver housing as a social good; more extensive solutions to the housing crisis will come from understanding the social role of housing in building household and community resilience.

Here, community housing models offer some evident clues, such as the ways in which housing is supplied and operated and the efforts to foster social connections and support in these communities.

While increasing the housing supply may moderate the affordability problem, policy-makers should be wary of vulnerabilities introduced by the market system beyond core housing needs, as our study reveals, especially for those who cannot afford home ownership.

To build long-term community resilience, public policies should pay attention not only to housing adequacy, but also to residential stability and the quality of life that homes and neighbourhoods provide.

Without a holistic understanding of the lived and social realities of what it means to be safe and sound at home, we lose crucial opportunities to meet important social policy goals through our housing plans and policy.

Our work is supported by the Partnership Engage Grants COVID-19 Special Initiative sponsored by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. This partnership is led by Dr. Yushu Zhu and Dr. Meg Holden at Simon Fraser University, in collaboration with Brightside Community Homes Foundation. This project also receives support from and contributes to the work of “Community Housing Canada: Partners in Resilience” (CHC), a 5-year academic-community partnership supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The CHC project is directed by Dr. Damian Collins at the University of Alberta (host institution), in collaboration with Civida.

Dorin Vaez Mahdavi and Meg Holden do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.