Excerpted from Warrior: My Path to Being Brave, by Lisa Guerrero. Copyright © 2023. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Dilip Vishwanat/Sporting News/Getty Images

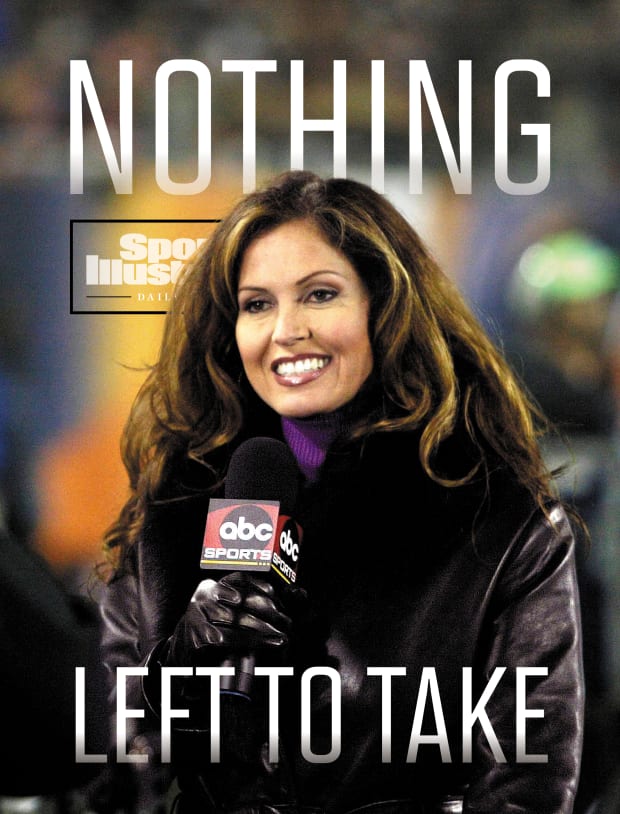

I recently rummaged around through some old boxes and found my VHS tapes from the year I worked as a sideline reporter on Monday Night Football, in 2003. I debated whether I should look at them. Would they confirm that I was as horrible as the media had said for the last 20 years? As I had come to believe myself?

I finally caved. I had the video transferred to digital, queued it up and then waited nervously for that moment when I sucked. But I waited and waited … and it didn’t come. Instead, I thought: I was good at that job! What was the media talking about?

When I finished watching, I broke down. I cried for my younger self, who had nearly been destroyed by that narrative about me. I cried, too, for the person who still carries around the humiliation of that experience.

Monday Night Football was both a dream job and a complete nightmare. But it didn’t start out that way. My role would be a new take on conventional sideline reporting. That’s what Freddie Gaudelli, the show’s executive producer, said when I interviewed for the position. He said he didn’t envision me as a traditional correspondent. Instead, he saw me more as a sports-meets-entertainment reporter. He explained that I’d report from the sidelines as well as the stands, interviewing celebrities and fans. If a couple decided to get married during a game, I’d officiate the wedding.

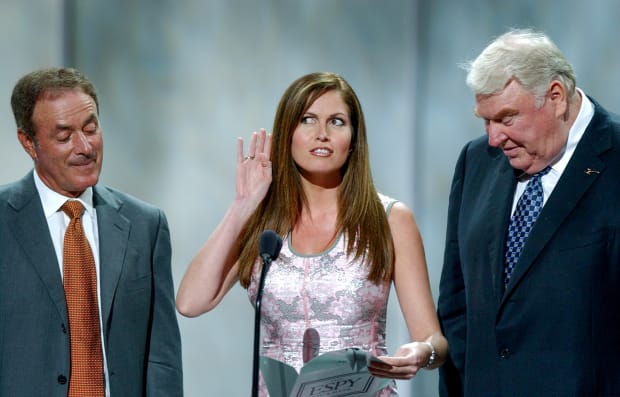

I loved everything about that job description. So I was thrilled when, a few days after my interview, I was offered the position. With close to 40 million people tuning in weekly, this was the biggest gig a woman could get in sports broadcasting. I’d report on the game with two sports broadcasting legends: Al Michaels and John Madden, who’d joined only a year earlier. But not only would I be part of an American institution, I would also be involved in its transformation into something more openly geared toward entertainment.

In late July, I flew to New York City for the official announcement of my hiring. Charlie Gibson, who hosted Good Morning America with Diane Sawyer, introduced me—and he sounded downright disappointed. Instead of asking about my previous work on television, he referred to my time as a cheerleader with the Rams, 16 years earlier. It seemed to me that Charlie didn’t think I was qualified. But I smiled wide. “I’ve been a sports reporter and anchor in Los Angeles for a decade,” I said, “and I was on The Best Damn Sports Show Period.”

He said he thought Melissa Stark, who I was replacing, was really good at the job. I kept the smile plastered on my face. “Everyone loves Melissa. She’s great. But I’m really excited to be the new sideline reporter.”

I waited for the next question. But Charlie wrapped it up and walked away. I stood on the set, shell-shocked.

Afterward, friends and family called, all with the same question: “What did you do to piss off Charlie Gibson?”

“Nothing.” The guy didn’t know me, and he’d never seen my work, but he already hated me.

I had no idea that this would be a sentiment shared by the sports media critics. Nearly as soon as my name was announced, the attacks began.

“Nothing but a teleprompter reader.” “A ridiculous new low for ABC.” “Another example of looks taking precedence over talent.” “A bimbo.” “A blow for women.”

I watched on television as Keith Olbermann, then an ESPN superstar, said that Al and John should resign in protest.

What had I done to ignite such anger? I was stunned, hurt and utterly baffled by the media’s reaction. It was as if my accomplishments during the past 10 years had disappeared. They didn’t mention my recent experience in sports journalism, including anchoring television broadcasts and conducting exclusive interviews with top athletes. Instead, they focused on what they called my “controversial past” as a cheerleader, actor and model, decades earlier.

John Cordes/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Most of the mainstream sports media was based in New York City or in Bristol, Conn., ESPN’s headquarters. If you weren’t on their radar, you couldn’t possibly have what it took. And then I showed up. My type was already a punch line to their jokes. Yet I was the one who had earned one of the most coveted jobs in sports. And that was unacceptable to them.

To make matters worse, I’d done a photo shoot for FHM, a men’s lifestyle magazine, which was scheduled to run at the beginning of the football season. This had been a strategic decision to promote my brand and raise my profile while I was at Best Damn. But when the media got wind of the photos of me clad in black-and-white lingerie, it reinforced their notion that I’d been hired on Monday Night Football for all the wrong reasons. When executives at Disney, ABC’s parent company, found out about the shoot, they were irate. I wasn’t the image they wanted for their family-friendly broadcast.

Apparently, though, the Monday Night Football executives really didn’t know what they wanted me to be. They feigned shock over the photo shoot … yet after hearing about it, the publicity department tried to negotiate for me to be on the FHM cover.

Then, for the show’s promotional photos, I posed in a powder-blue blazer next to Al and John. Yet the photos that made the cut, including on a Times Square billboard, weren’t from that official ABC photo shoot. Instead, without my permission, they superimposed a photo—in which I wore a gold-sequined tube top and a come-hither look—that was taken from a modeling gig I had done years earlier.

After the media attacked me, it seemed that Freddie’s attitude toward me completely changed. This was his second year as the executive producer of Monday Night Football, so he was probably terrified that I would be his undoing. When he interviewed me, I think he was impressed by my credentials and truly believed that we’d transform sideline reporting together. However, as we edged closer to the season, ABC seemingly decided to forgo the revamp. Instead, I’d be a traditional sideline reporter—a job I’d never done before, and didn’t feel qualified for.

The first regular-season game of that Monday Night Football season—my official debut—was between the Jets and Washington. Four former New York players had just been signed by their Week 1 opponents, and there were rumors of animosity between old teammates. Everyone was wondering whether they would be civil to each other. Would a fight break out?

A lot of eyes would be on me, too—judging me, writing about me, commenting on me. Any flub would be magnified. My outfit and makeup—even my lip gloss—would be scrutinized.

I had spent the week before the season opener researching the teams. I was up to speed on the players, the rivalries and what people were calling the “Jetskins” controversy. I had written up and memorized 30 story lines, as Freddie had asked. Then Freddie asked to see my work. He read it and explained that he would be rewriting my stories. He wanted me to memorize his words exactly. He told me I was not to improvise.

Michael Caulfield/Getty Images for ESPN

I believed that I knew what was behind this request. Freddie may have been embarrassed by the media’s depiction of me. I felt that he couldn’t fire me, because I was his first hire. Al and John had joined the show under legendary producer Don Ohlmeyer. So instead of firing me, Freddie would micromanage me. Maybe he thought he’d be the brains behind the bimbo. He painstakingly revised every piece I’d written. He replaced my conversational tone with a formal style that didn’t sound at all like me.

I’d been writing my copy for a decade, but suddenly I felt reduced to a ventriloquist’s dummy. When I delivered Freddie’s words, it was unnatural. It didn’t sound like me. I felt like an actress playing a role that I wasn’t meant to play. And there were critics who picked up on this. They would say I looked uncomfortable, that I glanced down at my notebook too much. But I had been directed by Freddie to deliver his script verbatim. If I didn’t, I’d get reamed out.

Today, when I talk to young reporters and journalism students, I tell them how important it is to speak in their own voice. “Imagine you’re talking to a friend,” I say. Looking back, I wish I’d told Freddie that I’d write my own copy. I prided myself on my conversational tone and storytelling ability. But I’d lost that confidence. I’d been so beaten down by the critics that I believed Freddie knew what was best for the broadcast.

That first game ended without incident. I felt like I’d even proven my detractors wrong. Afterward, we were live for another 10 minutes to do a postgame wrap: Al and John would impart their final thoughts while I did a hit with whomever they deemed the game’s most valuable player. Since Washington had won, 16–13, I’d talk to Patrick Ramsey, their quarterback. And because I was the Monday Night Football sideline reporter, I got first dibs … but other journalists would do their best to get to him first.

As Ramsey headed toward a postgame prayer circle that had formed, I rushed toward him. Al would be tossing to me in 20 seconds, so I picked up my speed and galloped across a mud puddle, my cameraman right behind. I spied another reporter closing in on my quarterback. I didn’t recognize the guy and figured him to be a local writer—no camera, just a tape recorder and what appeared to be a Members Only jacket. Media relations would normally run interference for me, but I had lost the guy in the mad dash. I heard Al in my earpiece start to send his toss-down to me on the field—and then I felt a crack on my left ear so hard that for a second I thought I’d been hit upside the head with a shovel.

I looked to my left and realized the shovel was actually the other reporter’s elbow smacking the side of my head, pushing my earpiece painfully far into my head. “C---,” he hissed as he brushed by me.

I headed toward the jerk. But Al’s voice in my earpiece reminded me that I had more pressing business. I grabbed Ramsey and quickly collected my thoughts. Then I asked him about his pregame conversation with his former teammate Laveranues Coles.

Buy Warrior: My Path to Being Brave

Suddenly, Freddie was yelling at me through my earpiece.

What the hell was wrong? What had I done to upset him?

That’s when I realized Ramsey was looking at me as if he didn’t understand my question. I replayed in my head what I’d asked him. I’d asked about his former teammate. They were current teammates!

It sounds like a silly mistake. And I immediately corrected it on-air. So what? But there was nothing silly about this mistake. I knew it instantly. In the eyes of the press and my bosses, I’d just confirmed everything that had been said about me. I’d provided all the haters with a reason to rant on sports radio, or bitch on their blogs. I was that stupid bimbo, just like they’d said all along.

Freddie was still yelling as I walked off the field. He wanted me to come to the production truck, immediately. I walked over, feeling sick, my hands shaking. I swallowed hard. Then I opened the door and braced myself.

Freddie’s head snapped toward me as he demanded an explanation for my mistake. Freddie is a short guy. But at that moment, he reminded me of a hulking, ’roided-out linebacker, about to deliver a vicious hit that would send me off the field on a stretcher.

I looked at the floor and closed my eyes as I tried to calm myself while formulating some kind of articulate explanation. I knew it was hopeless. There was nothing I could say to fix it.

“I had a brain fart.”

Freddie’s eyes widened. I’m sure my response must have infuriated him. I rushed out of the trailer and into the waiting car outside. The minute the door slammed shut, tears streamed down my face.

The driver shot me a concerned look. “Should I take you to your hotel?”

I nodded and continued to blubber during the 15-minute drive. Before we pulled up to the entrance, my driver handed me a box of tissues. “Don’t let the bellman see you like that,” he said. “They know who you are, and they gossip. When I open your door, laugh like I told you something funny.”

I was touched by his concern. “Did you see it?” I asked, hoping that someone removed from the debacle might give me an honest take on it. Maybe it wasn’t so horrible.

“Yup,” he said. “It was bad. And if you don’t mind me saying, that color jacket doesn’t look very good on you, either.”

When I got to my room, I dropped my bag on the floor. I took off the jacket and stared at it. The driver was right: The blazer was ugly. I tossed it into the trash. Then I headed to the toilet, where I threw up until there was nothing left in my stomach except a knot that refused to go away for the rest of the season.

I started having recurring nightmares shortly after that season opener. In one, it was the middle of the night and I stepped out of a limo after returning from another game. As I headed toward my front door, a guy wielding a knife jumped out of the bushes and rushed toward me. I tried to scream but couldn’t.

In another, I was naked on the football field. I was petrified, thinking that this was exactly the ammunition the media needed to prove that I’d been hired for my body rather than any talent. Freddie would definitely fire me. Worst of all, in the dream I couldn’t remember anything about the teams. I didn’t even know who was playing. Al threw to me. I couldn’t speak.

Night after night, I’d jump up in bed, drenched in sweat, my heart hammering. I’d feel a pang of relief when I realized these were just bad dreams. But the relief would quickly be replaced by despair when I remembered why I was having such nightmares. Then I’d cry.

I slept for only about three hours a night, but I didn’t want to get out of bed. I barely ate. I’d take a few bites of food but couldn’t swallow it. I’d try to distract myself with a movie or a TV show, but I couldn’t follow the plot. I had absolutely no attention span.

Kirby Lee/AP

Years later, when I relayed these symptoms to my uncle, a licensed psychiatrist, he explained that I’d been suffering from a bout of situational depression. Looking back, it’s pretty clear that something was wrong, but I was too exhausted and too anxious to deal with it while it was happening.

After my gaffe in the season opener, the media launched a new attack: “Guerrero is offensive to any female with brains.” “Guerrero insults any male who not only loves the game but respects it in the morning.” “[Guerrero was] there strictly as eye candy for the predominantly male audience, and to pretend otherwise is to further insult whatever intelligence the audience may have.” “They don’t call it the boob tube for nothing.”

Those were just the newspaper columnists. I was eviscerated, too, by TV commentators. But the radio guys were the worst. There was an ugly misogyny pulsing through sports-radio airwaves, and I was their perfect target. They spoke in horrible hyperbole. To them, I was the worst. I was everything that was wrong with sports. I was everything that was wrong with feminism. I alone had set women back decades. They’d attack my clothes, my hair (why was it so long?), my lip gloss (I wore too much), even my nail polish (how dare I wear red—I must be a whore!).

But through all of that, Monday Night Football’s ratings actually went up that year, for the first time in a decade. When asked about the increase in viewers during a weekly phone presser, Al called it “the Guerrero Factor.”

Freddie’s criticisms, though, obliterated all other sounds. After my blunder, he became even more critical. The media would obsess about how terrified I looked on the field. They blamed it on how uncomfortable I was on the job.

Imagine having your boss yelling at you while TV cameras are on you, while your image is being projected into millions of homes. In retrospect, it’s no wonder I looked terrified.

Looking back, it’s hard to believe that was me. When had my confidence started to wither? Was it when I first walked into a locker room, years earlier, and was subjected to whistles, catcalls and demeaning comments? Or when I had my ass grabbed by an anonymous colleague during a media scrum? Was it when I’d been taken off Best Damn’s Super Bowl coverage because I wouldn’t sleep with an executive at Fox? Or when a comedian asked on TV whom I’d f---ed for my job? Every bit of this misogyny had worn me down until I lost my edge, my sparkle, my bravery.

The worst part about it was that I kept hearing the same thing: “You are the luckiest woman in sports.”

How could I be depressed when I was the luckiest woman in sports? What was wrong with me? I was at the pinnacle of my career. I felt I should be grateful for this incredible opportunity that so many others desperately wanted. I decided that the executives and producers knew better than I did how I should look, act and speak.

I wish I had been more courageous. But I knew that if I quit, the media would say that it was because I couldn’t handle the job. I wish I’d said, “Freddie, I’m not going to let you talk to me this way. Don’t ever yell at me again.” No one should put up with their boss’s anger. No one should cry before and after work. No one should be so scared of doing their job that they vomit, shake and have nightmares.

How had I gotten to this place where I had lost my boldness, my bravery?

I was so ashamed and humiliated by the mistake I made during that first game that I really thought I deserved the criticism and abuse hurled at me. I couldn’t let the negative press just roll off me. Instead, I absorbed each comment and allowed them to define me. They were all I thought about. They echoed in my head during the day and kept me up all night.

And I wasn’t Lisa Guerrero for that entire season. I didn’t look like myself. I didn’t sound like myself. I was utterly lost.

Meanwhile, my friends and my dad were incredibly proud of me. Everyone I knew was thrilled for me. And I didn’t want to destroy the illusion. I usually told my dad everything, but I didn’t want him to know about the dark place I was in.

I had started dating a baseball player, Scott Erickson, and he was the only one who understood because he’d see me crying. He’d also been to some of the games; he’d listened in on the headset and heard Freddie yell at me. He was shocked and appalled by Freddie’s language and disrespect. (Freddie would years later tell me, on separate occasions, that I misremembered my experience on Monday Night Football. He said he never yelled or cursed at me and that he had done his best to support me. There were others, he added, who said the verbal abuse “just didn’t happen.”)

Scott saw how the job had changed me entirely. The smart-ass chick who’d given his buddy a hard time at the bar a year earlier had morphed into a sobbing mess. “You should quit,” he’d tell me. “It’s not worth it.”

He was concerned about my mental health. He saw me having a breakdown up close and in slow motion.

That Thanksgiving, Scott proposed to me at his home in Lake Tahoe. He got on his knees on a giant boulder overlooking the lake at sunset. After I said yes, he popped open a bottle of champagne.

But when I took a sip, I couldn’t taste it. One of the side effects of my depression was that food and drink had lost their flavor. As much as I tried to push Monday Night Football out of my head while celebrating with my fiancé, it was with me, taunting me. I gulped down the champagne and smiled, but I remembered what was waiting for me when I headed back to work after the holiday.

Our engagement was announced on the broadcast that week. Anyone watching would have looked at me, a big smile on my face, and been envious of my life. But I was thinking: Who decides to get married when they’re also considering killing themselves?

That’s how bad I felt. I was planning a wedding while considering suicide. Then, I would become even more depressed about being depressed during what was supposed to be the happiest time of my life. I’d never thought about suicide before. But I wasn’t thinking clearly. I was worn down from the lack of sleep and nourishment. And on top of that, I learned that I was pregnant.

Besides Scott, I didn’t confide in anyone about what I was going through. I was so consumed with Monday Night Football that I had become alienated from my friends. There were people at work who saw what I was going through … but we never talked about it. They weren’t friends, so I suppose they didn’t feel comfortable asking me if I was O.K. And this added to my loneliness and depression.

But, being the actress, I plastered a smile on my face and I hit the road for the next game.

It was during the first quarter of a Monday Night Football game that I felt some discomfort on the left side of my stomach. I took a few deep breaths, wondering whether I’d eaten something that hadn’t agreed with me. But I pushed through the pain and did my reports. By the second quarter, the pain had intensified. When I felt a dampness between my legs, I thought: Oh, that’s it. I got my period.

And then it hit me. No; I was having a miscarriage.

The second quarter was ending, and I desperately wanted to get to the bathroom. I could feel blood leaking out of me. I was weak and dizzy. But I had one more hit to do. I also had to chase down one of the head coaches for a question for the first-half summary. I thought I could run to the bathroom and be back in time. Before a game, I’d always scope out the officials’ bathroom, because I’d have only a few minutes’ break during halftime. The bathroom was in the tunnel behind me.

“I’m going to the bathroom,” I told my assistant, a young guy whose job was to race around the field with me.

He looked at me as if I were completely insane. “Don’t! They’re about to throw to you.”

So I delivered my live report. I was dizzy and nauseated. I don’t remember ever feeling more alone than at that moment when I reported on the game to an audience of 40 million, while surrounded by 100,000 football fans. Despite the pain, I even reminded myself to stand up straight. During our Wednesday-morning phone calls, Freddie would ream me out for my bad posture.

I stared at the camera, but I could barely see. The pain was excruciating. I heard myself mispronounce a player’s name and knew I’d hear about it later. I was losing a pregnancy and worrying about a mispronunciation!

As soon as I finished, I raced off to interview a coach. Then I headed to the bathroom. As I sat on the toilet, I couldn’t believe the blood that was pouring out of me. It had soaked through my pants. People banged on the door, but I couldn’t move. I shoved a bunch of paper towels in my underwear. It never occurred to me to tell anyone. It never occurred to me that maybe I should have gone to a hospital or called a doctor or, at the very least, sat out the rest of the game. The only thought that crossed my mind was that I could get through the rest of the game as long as I buttoned up my long winter coat. That way, no one would see the blood.

I haven’t thought about that day in a long time. I can’t believe how utterly detached I was from what was happening to me. I was having a miscarriage, and I was worried about bloodstains being visible on television.

I didn’t see that I was on a dangerous downward spiral. I didn’t see that I had become completely detached from reality. I didn’t see how sick I was—mentally and physically. I was completely checked out.

When the game ended, I was supposed to go to the production truck to talk to Freddie. Instead, I headed back to the bathroom. I pulled out my earpiece to mute him. Then I sat on the toilet. There was so much blood.

I never made it to the production truck. Instead, I got in a limo and headed to the Disney jet. I waited until Al had settled into his seat. Then I headed to the bathroom, changed my clothes and dumped my underwear and pants in the garbage can. I looked into the mirror and didn’t recognize the pale, gaunt, scared and so very tired woman who stared back at me.

Later, as the plane ascended into the clouds, I thought about all I’d lost on those sidelines—my dignity, my courage, and now my pregnancy. There was nothing left to take. At that moment, I vowed to stop letting Freddie have so much control over me. Nothing he could do or say could be worse than what I’d just experienced, alone on the sidelines in front of millions of people. The football season was coming to a close. During the last few games, I stopped memorizing Freddie’s notes. I spoke in my own voice. I pulled out my earpiece during my reports. That way, if Freddie was screaming at me, I would never know.