The UK economy has been dogged by slow growth for a long time. Combined with even slower growth in productivity, it has meant virtually no increase in living standards for the average family over the past decade.

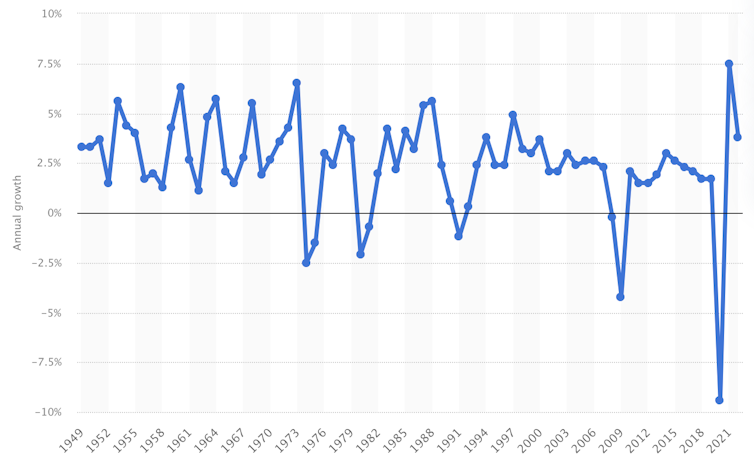

Now the new chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, has unveiled what he says is a radical plan to get growth back to its historic average of 2.5% per year. This would be an increase of about a percentage point, lifting living standards and providing more money for public services.

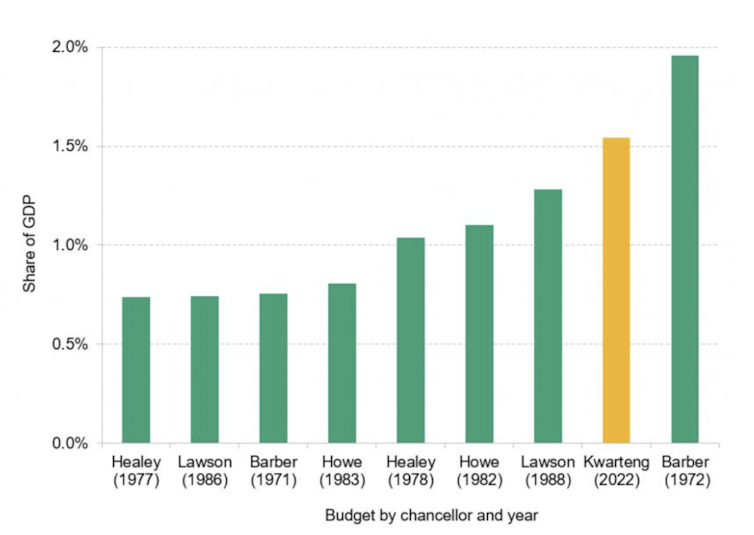

The central part of Kwarteng’s mini budget involves cutting taxes in the hope of providing greater incentives for individuals and businesses to work harder and invest more, in what are the biggest net tax cuts from a chancellor since the early 1970s.

Much of this will benefit the better-off more than those on lower incomes, but the government argues that higher growth and not redistribution is the priority, and that this will benefit everyone as the economic pie becomes bigger. So will this work?

Net tax cuts of UK chancellors

First, the highlights. The increase in national insurance is being cancelled, the highest rate of income tax and the cap on bankers’ bonuses abolished, and the basic rate of income tax cut from 20% to 19% in April. Stamp duty on house purchases is also being cut, especially for first-time buyers.

The hike in corporation tax scheduled for April will not now go ahead, while a variety of other incentives are being introduced to stimulate investment and reduce the burden of regulation, including lower taxes for the self-employed. Added together, these measures will cost £45 billion per year.

In addition, the government is spending a huge amount to keep energy bills down. Moderating the planned rises for households will cost an estimated £60 billion per year for the next two years, together with circa £30 billion to help businesses in the next six months. The actual cost will depend on future gas prices.

Growth dividend?

The evidence is inconclusive as to whether lower tax rates always incentivise individuals to work harder and unleash their entrepreneurial spirit. In the UK, many may use the extra cash to enjoy more leisure time – particularly with the number of people in the workforce substantially reduced since the pandemic, especially those over 50.

Meanwhile, the fact that poorer people are set to gain relatively little from the tax cuts may explain why the government is planning to sanction those who work fewer than 15 hours a week and are not actively seeking jobs.

Ironically, in the wake of Brexit the government also sees increased migration as a way to increase economic growth by adding more workers to the economy. However, increasing the size of the workforce does not necessarily boost productivity (output per worker) – the key to higher incomes.

Most likely, the incentives for business investment will therefore be crucial to achieving any step-change in growth, together with previously announced plans to raise skills.

UK GDP growth 1949-2021

Business investment in the UK has been historically much lower than that of its main competitors. However, successive cuts to corporation tax have made little difference.

The same goes for the many previous schemes to incentivise specific investments, including the Johnson government’s “super-deduction” for investment in plant and machinery.

With Kwarteng’s business incentives also including new low-tax investment zones and planning reform, it remains to be seen whether this will make much difference. With a looming recession, high inflation, the energy crisis, supply shortages and difficulties in recruiting skilled workers, it is hard to envisage a dramatic shift in the short term.

The public finances

The government has suggested that if it succeeds in its objective of boosting annual growth by one percentage point by 2026-27, there could be an extra £47 billion in tax revenues. This is a preliminary forecast which has not yet been scrutinised by its Office for Budget Responsibility.

Yet in the short term, a big squeeze on public spending is on the cards. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the effect of inflation will be to cut departmental budgets in real terms by £18 billion compared to what was planned in the last spending review, and that is before public sector pay increases.

The Treasury’s own Growth Plan 2022 says that “keeping spending under control” is a key part of its commitment to fiscal responsibility.

Regardless, the planned £90 billion in energy subsidies and £45 billion in tax cuts will deliver an enormous stimulus to the economy. To curb the extra inflationary pressures that this will exert, the government will be counting on the Bank of England to keep raising interest rates sharply. But it is not clear how the tension between these two objectives will play out.

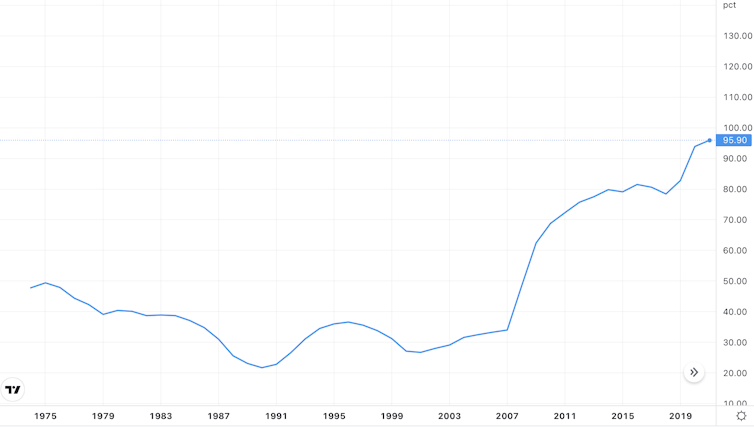

Equally unsettling is the fact that the measures are set to raise the government’s deficit from £100 billion to nearly £200 billion next year, or almost 10% of GDP. This raises the prospect of UK government debt continuing to rise as a proportion of GDP in the medium term.

UK government debt as a % of GDP

The government argues that over five years, if its strategy boosts growth, it would add billions of pounds to tax revenues to service the debt, as well as increasing the overall size of the economy and therefore reducing the debt-to-GDP rate. The markets have nevertheless reacted with concern, dumping UK government bonds and the pound after the announcement.

Where this leads

The government is clear that its reforms will only deliver benefits over the medium term. But short-term economic problems could derail the plan and threaten the chances of an election victory – most likely due to be contested in 2024.

The model of Liz Truss’s new government rehashes the strategy of the Thatcher government in the 1980s, where tax cuts and deregulation arguably helped to boost growth. But tax rates were much higher then, and the size of the state industrial sector was much larger.

Read more: Why Liz Truss is no Margaret Thatcher when it comes to the economy

A more worrying comparison, where the “dash for growth” foundered over short-term economic problems, might be the “Barber boom” introduced by the 1970-74 Conservative government. A huge economic stimulus led to soaring inflation, public sector pay strikes, and a foreign exchange crisis, leading to the government’s defeat in the 1974 election.

This is a dramatic shift in government policy that faces many obstacles. There may well be a rocky road ahead before we see whether this gamble on growth yields the result that its proponents are promising.

Steve Schifferes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.