Breathe in, breathe out — new brain scans have revealed that mindfulness meditation really does relieve pain, and not because it acts like a placebo.

Mindfulness meditation refers to the ancient practice of drawing attention to the present moment in a nonjudgmental way — releasing thoughts of looking silly or doing it wrong, for instance. New research finds that this practice activates specific lines of communication, or pathways between brain cells, that can reduce the perception of pain.

These pathways differ from those stimulated by the placebo effect, and their activation results in more powerful pain-relieving effects than sham treatments.

These recent findings, published Aug. 29 in the journal Biological Psychiatry, were drawn from healthy people who were exposed to a brief, painful stimulus and then used different methods to alleviate that pain. If the same results show up in patients with chronic pain, mindfulness meditation could be a promising, active therapy option, the study authors argue.

Related: Meditation may have shaved 8 years of aging off Buddhist monk's brain

"Millions of people are living with chronic pain every day, and there may be more these people can do to reduce their pain and improve their quality of life than we previously understood," Fadel Zeidan, study co-author and a professor of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement.

Mindfulness meditation has been used for millennia in various cultures for pain-relief purposes. However, scientists have questioned whether some of its purported pain-relieving effects actually stem from the placebo effect. This phenomenon causes people to perceive that their symptoms have improved even though they received an inactive treatment that doesn't directly treat their condition.

In the new study, Zeidan and colleagues designed a series of experiments to learn more about how mindfulness meditation affects people's perception of pain.

They recruited 115 healthy volunteers and asked them to undergo one of four interventions. One group undertook guided mindfulness meditation, led by experienced instructors. Another group participated in a "sham" mindfulness meditation that involved only deep breathing and no cues to tune into their breaths in a nonjudgmental manner. A third group applied a placebo cream — namely, petroleum jelly — to their legs and were told it had pain-relieving effects, while the remaining group just listened to an audio book.

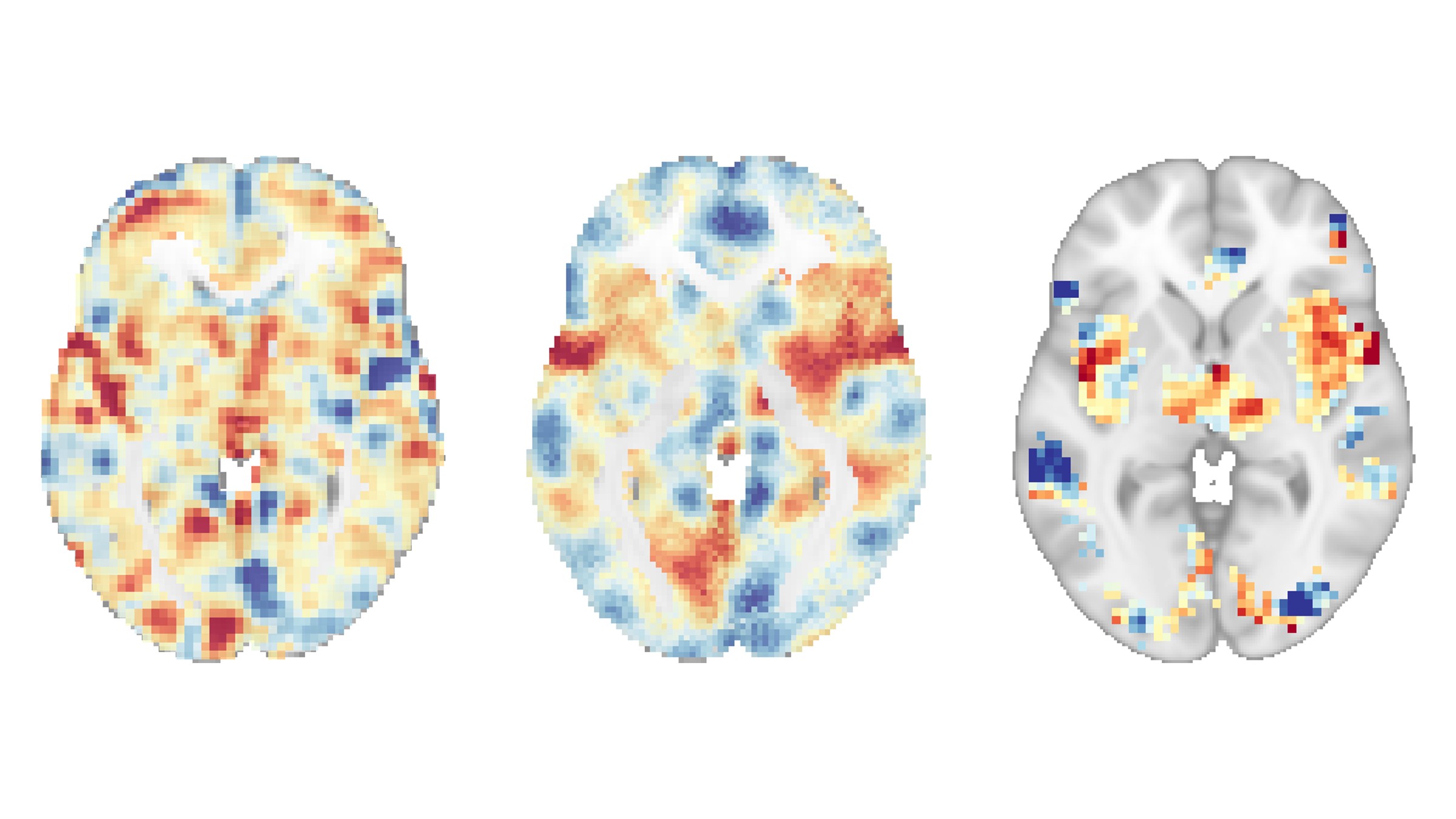

The team did initial training sessions to get people used to the experimental setup and teach the meditation approaches. Then they got down to collecting data using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which tracks the flow of blood through the brain to determine which areas are most active at a given time.

With the participants' permission, the researchers applied a very hot probe at around 120 degrees Fahrenheit (49 degrees Celsius) to the backs of their legs while they were in the scanner. They scanned the participants' brains before and after the interventions, tracking the changes in activity.

Each time the probe was applied, the participants also rated the pain they experienced on a scale of 0 (meaning "no pain") to 10 (the "worst pain imaginable"). Overall, the researchers found that the group who practiced mindfulness meditation reported significantly greater reductions in pain intensity than those who did the other interventions.

The brain scans uncovered another, perhaps more surprising finding: Mindfulness meditation produced significantly greater reductions in brain activity associated with pain perception and emotional experiences of pain than the other interventions. These patterns of brain activity — respectively known as the neurologic pain signature (NPS) and the negative affective pain signature (NAPS) — had been established in prior studies of pain perception.

In other words, the brain scans confirmed what the participants' pain reports had hinted — that mindfulness meditation actively treats pain.

On the other hand, the petroleum jelly only changed the activity of the so-called Stimulus Intensity Independent Pain Signature-1 (SIIPS-1) pathway. Based on previous research, this pathway is involved in setting our expectations of pain relief from a given treatment. This can then shape how we perceive pain.

This finding suggests that mindfulness meditation engages different parts of the brain than the placebo effect and that it directly turns down brain activity that normally boosts feelings of pain.

These "two brain responses are completely distinct, which supports the use of mindfulness meditation as a direct intervention for chronic pain rather than as a way to engage the placebo effect," Zeidan said.

That said, the short-term pain tested in the study is not directly comparable to chronic pain, so more work will need to be done to confirm meditation's usefulness in that context.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!