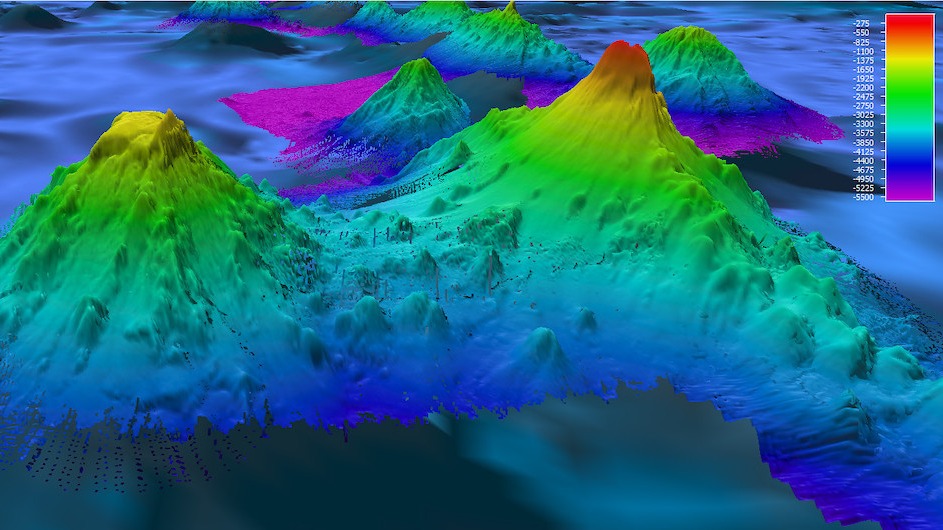

High-definition radar satellites have revealed more than 19,000 undersea volcanoes around our planet, providing scientists with the most comprehensive catalog of seamounts ever created. The new compendium, which was published April 6 in the journal Earth and Space Science, could provide a better understanding of ocean currents, plate tectonics and climate change.

Prior to this, only one-quarter of Earth's seafloor had been mapped using sonar, which uses sound waves to detect objects hidden underwater. A 2011 sonar census found more than 24,000 seamounts, or undersea mountains formed by volcanic activity. However, there are more than 27,000 seamounts that remain uncharted by sonar, according to the Science article.

“It’s just mind boggling,” David Sandwell, a marine geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who worked on the survey, told Science magazine.

Related: Scientists find strange underwater volcano that 'looks like a Bundt cake'

However, the new study shows that scientists don’t need to rely on sonar surveys to investigate what’s going on under the ocean. Radar satellites not only measure an ocean's height but can also see what's lurking in the water's inky depths, offering a better representation of the topography of the seafloor. Scientists pulled data from several satellites, including the European Space Agency's CryoSat-2, and found that they could detect underwater mounds as small as 3,609 feet (1,100 meters) tall, which is the lower limit of what constitutes a seamount, according to the Science article.

With this technology, scientists predict they can estimate the heights of small undersea volcanoes to an accuracy of approximately 1,214 feet (370 m), according to the study.

So far, researchers have mapped a collection of seamounts in the northeast Atlantic Ocean that could help explain the evolution of a mantle plume that feeds more than 100 volcanoes in Iceland. These updated maps will also provide a better understanding of ocean currents and "upwellings," which occur when water from the bottom of the ocean churns upward to the surface — a phenomenon that scientists think could be "concentrated at seamounts and ridges," according to the Science article.

"There's a zoo of interesting things that happen when you have topography," Brian Arbic, a physical oceanographer at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor who wasn't involved with the study, told Science.

You can read the full Science article here.