This article is part of Guitar World's series of interviews and features with artists addressing and raising awareness around themes of mental health, particularly as they relate to musicians.

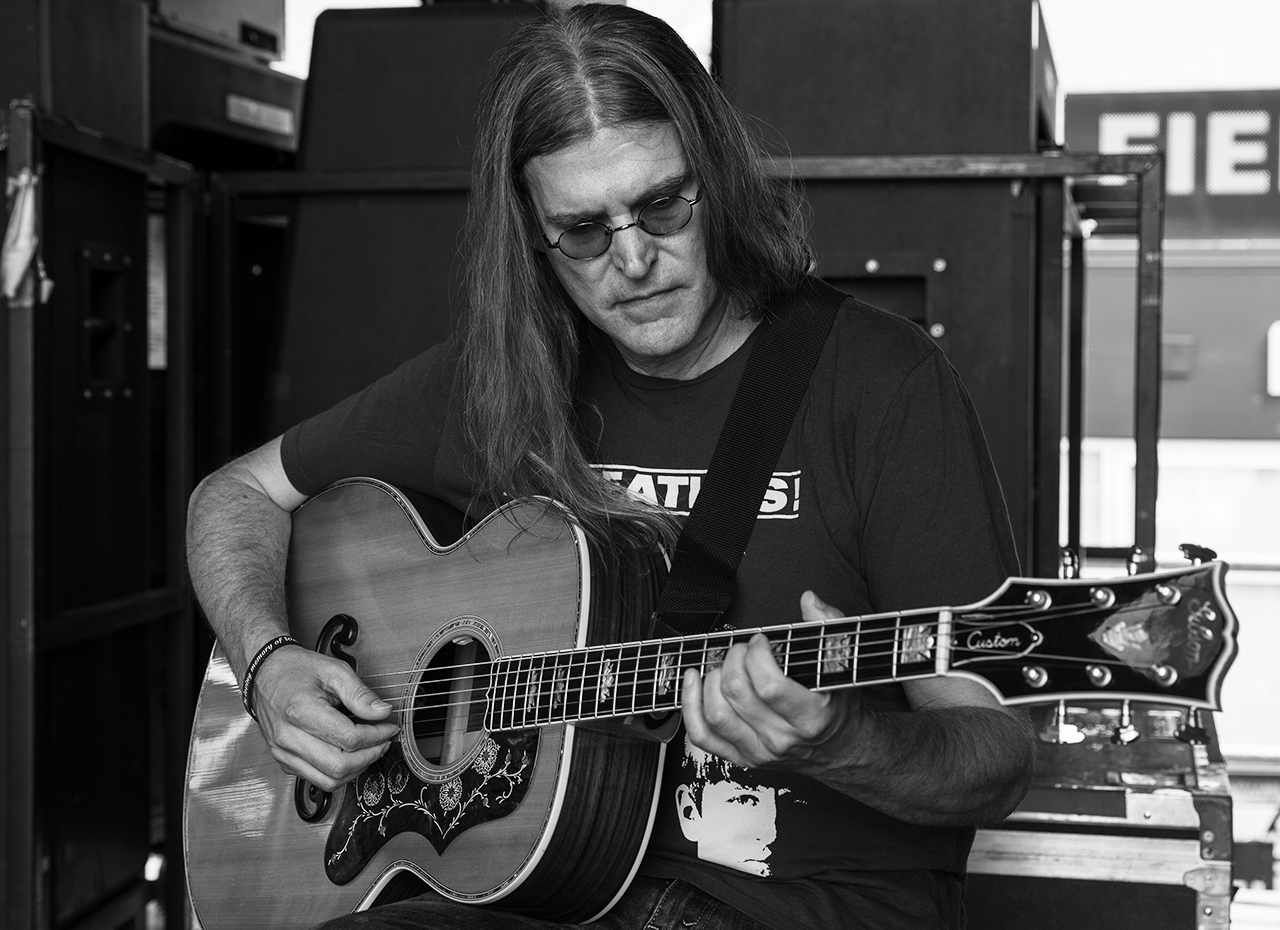

Jon Conley’s passion for music began as a toddler in Paragould, Arkansas. “Anytime music would come on television, it pulled me in and I would grab my toy guitar,” he recalls.

He began playing the actual instrument at age seven and joined his first band at 10. After college he spent four years in Branson, Missouri, playing 700 shows a year backing country artists.

In 1995, he and his wife moved to Nashville. He landed his first touring gig six months later, and spent five years as guitarist in Wynonna Judd’s band.

Skilled on guitar, fiddle, bouzouki, banjo, bass, mandolin, and vocals, in-demand session and touring musician, producer, and songwriter, Conley’s resume includes Johnny Cash, Glen Campbell, Luke Combs, George Jones, Taylor Swift, Joe Walsh, Steve Miller, Sammy Hagar, Vince Gill, Amy Grant, John Mayer and Leann Rimes.

He joined Kenny Chesney’s band in 2011, and he says It’s the perfect gig, allowing him to showcase his many talents in a supportive, inspiring environment.

“Kenny is all about connecting with each other and with the crowd, bringing together people from all walks of life to experience happiness,” he says. “There’s something really healthy about those collective connections, that positive energy.”

Behind the music he spent years battling depression, anxiety and OCD. Before beginning therapy and medication, he did his best to power through the dark times, navigating a steady climb to success.

“Melodies and lyrics moved me emotionally when I was really young. When you’re a kid, why would you think that anything’s different? Then you start noticing, ‘Wait a second; some people aren’t, so why am I?’ It took years to connect those dots.

“It’s a mixed blessing because it allows you to feel things very deeply – so when you play music, you can go to deeper places. But it comes at a price because it can be draining sometimes. You feel like you got socked in the gut if it’s a sad song, or a high if it’s a happy one.

“When I let the music direct me, as opposed to me directing the music, it’s spiritual. It’s something bigger than you. Any time I play with other musicians, interact with them, and that magic happens, it’s humbling. You know it’s super-rare, and not only do you get to hear it, but you get to make it, too.

“I feel that God uses music in such a powerful way. A lot of music comes from pain – when you write something sad, or even when you write something happy to distract from the pain, you share it; other people share it; and it’s healing.

“I read the Psalms where David was so excited that he danced publicly to celebrate, and he was chastised for that; but there were other times when he was so depressed that he couldn't get out of bed and would cry out to God to heal him.

“I also look to Jesus, who had anxiety so deeply that he sweated drops of blood the night before he was crucified. If anxiety is a sin, then Jesus sinned – and I don’t believe he did. I don’t believe these feelings, this humanity that we deal with, are a sin.

You have to find those people where you know you can say, ‘Today’s a hard one.’ Being able to lean on somebody like that is really important

“I think people are becoming more aware that mental health is complicated. Eating right won’t heal it. Music isn’t enough to heal it. Counseling won’t solve everything. You can’t medicate or exercise or pray it away. If we’re just supposed to pray things away, why do we take cough medicine or Advil?

“It takes all of those things, all of it together, day by day, to be healthy. I don’t want to project on anyone else; but for me, I believe God works through all those things.

“It’s not like I’ve lived a life of sorrow or a constant state of anxiety. There are a majority of moments where I feel very even and healthy. But I know it can happen at any time, and sometimes you don’t know why.

“Trying to be present and live in the moment helps a lot. So does having bandmates and friends who notice and who I notice. It’s great to be there for somebody and say, ‘I get it and I'm here for you,’ and they know and trust that.

“Thank God there have been people there for me when I’ve been in that situation. Someone was astute enough to see that I was struggling and tell me, ‘It’s okay. It’s all right.’

“We’re getting better as a society – but sadly, we don’t like to show that we’re in a bad place. We don’t want to bring people down. The hardest part is when you make yourself vulnerable to somebody, but they don’t reciprocate. Sometimes you can feel even more alienated; so you have to be careful.

“You can’t just do it with anyone. You have to find those people where you know you can say, ‘Today’s a hard one.’ Being able to lean on somebody like that is really important.

“My depression isn’t constant. It’s not the worst it can be all the time. But periodically you have these times and you have to fight so hard and develop coping skills so that you can not only survive, but thrive.

How many people feel ugly when they’re the furthest thing from it, or feel stupid when they’re unbelievably intelligent? So many feelings we have are just not accurate

“You can be doing great – but then you get to that point and you get caught up in the shoulds: ‘I should be better,’ ‘I shouldn’t have to still deal with this.’ Pride or fear can get in the way. You don’t want to admit it to yourself, and sometimes it’s just too much.

“My parents, my brother and my wife have always known, and my brother finally said, ‘Man, I really think you’re depressed and you should get some help with this, because you’re doing all you can do.’

“I was never suicidal – I didn’t have those tendencies – but during the 1990s there was a stretch when I had a fear of flying. I was on a flight one day and I realized, ‘I’m not afraid to die.’ Something in me said it would be relieving. I never made a plan or pictured it, but there have been times when I had thoughts that at least it would all be over.

“But having those thoughts also keeps me in check. Just because you feel like something doesn’t mean you are that something; and just because you may feel life isn’t worth living doesn’t mean it’s true.

“Being a person that feels things deeply, I know that feelings have their place – but they’re not always trustworthy. Many times we feel things that are not correct. It’s important to remind yourself of that.

“How many people feel ugly when they’re the furthest thing from it, or feel like they’re stupid when they’re unbelievably intelligent? There are so many feelings we can have that are just not accurate.

“I started taking medication in the 1990s. It’s no different than taking medication for blood pressure or diabetes or whatever it may be. Another thing that’s frustrating about mental health – and society in general – is that we tend to be so extreme.

“We want to brand something as way over here or way over there: we’re completely healthy or completely not, or we view someone else that way. There’s such a vast spectrum of healthy and unhealthy – with mental health, every bit as much as physical health – but we’re not as open to talking about it.

You’re less than 1 percent of the population. But less than 1 percent is how many million people?’ A lot of people deal with what you deal with

“OCD is a perfect example. I never heard the words ‘obsessive-compulsive disorder’ until I was 22, and when I found out there were tons of people just like me, I was like, ‘Oh gosh; I’m not this special page in a book where this guy was just a freak and had this condition! It’s not that at all!’

“Not knowing what OCD was, I didn’t know to tell anybody. I didn’t have the balanced perspective: ‘Are you just like everybody else? Well, no, because you’re less than 1 percent of the population. But less than 1 percent is how many million people?’ There are a lot of people who deal with what you deal with.

“As a society we have to stop dehumanizing people. We are all human beings with our challenges, hurts, pains, joys, successes and failures, and all those things are relative to the person experiencing them.

“Comparing our problems – whose are worse, whose aren’t – is dangerous, because where does that begin and end? What we should do is be supportive and be here for each other. It’s important to be seen and heard, and if we can do that for each other, and help each other get on with it, we’ll be good.”