For an industry that revolves around "making things," fashion has somewhat strayed from the "making." We've entered a Bizarro World where clickiness is currency and expansive themes are trumped by trends that fit neatly into eras, 'cores, and aesthetics. For the designers who are game to gamble, it's a race to capture the zeitgeist's whims or find a gimmick that hacks our short attention spans.

But the rise of quick-hit style belies another reality. One where public opinion is overlooked in favor of nurturing a more valuable connection: the one between a designer and their craft. For these creators, the only way to stay upright on fashion's high-wire act is to keep their heads down and eyes on their work. Their artistry is intimate—a bond forged from hundreds of hours spent crocheting by hand, setting gems in gold, and measuring stitches down to the millimeter.

These 10 designers, both contemporary and veteran, are perfect examples of those who have mastered their métier. For a glimpse into their process, we asked them about their respect for tradition (or their predilection for subversion), how they merge the past with the present, and why beauty is in the details.

Rachel Scott, Diotima

Rachel Scott of Diotima treats her textiles like clay. As she tells it, yarn, cotton, and silk are meant to be manipulated and molded to her vision.

"The way I work with crochet is quite unique in that I will drape it like a fabric and use it to deconstruct familiar silhouettes," says the Jamaica-born artist, who won the CFDA's 2023 Emerging Designer of the Year Award. You could describe her methods as unconventional. "[Design] is a constant play amongst all the elements and my creative process is constantly in flux. Ideas truly materialize in the moment of fitting: I can see how the materials move, what remains static, how the wearer interacts with the piece—those moments inform the next step," she says.

Above all, Diotima serves as Scott's love letter to Caribbean craftsmanship. Pulling inspiration from dancehall parties in the '90s and photographs of Caribbean women from the 1800s, Scott's work is intricate and beautifully complex—not something you can casually pick up off the rack. She's known for her peek-a-boo lace inserts, crystal-embellished macramé, and ornate doily-style crochet. "Every piece has an element of the hand, whether it is crochet, hand-stitching to connect seams, macramé, or hand-applied crystals," says the designer, a graduate of Istituto Marangoni Milano.

She hopes her reverence for the handiwork of her heritage inspires "an expanded sense of the places craftsmanship [and] luxury come from." Scott cites her own production as an example. "I work with crochet artisans in Jamaica, I work with tailors in New York City, and I work with embellishment and other hand techniques in India. This freedom and re-evaluation of value," she adds, "is very exciting."

Raul Lopez, Luar

Even in its early stages, "emerging" never felt like the right descriptor for Luar. With a point of view as sharply realized as Raul Lopez's, the New York label hit the scene in 2011 feeling already emerged. The Dominican-American designer defines luxury as uninhibited, community-oriented, and, most importantly, accessible: His ready-to-wear typically caps at $1,000 and accessories average around $300, while Luar Basics, a newly launched sub-line of sweats, tees, and cozy essentials, retails entirely under $500. "We want our Luar pieces to be heirlooms," he says.

The Brooklyn-based creative makes modern-day power pieces with grit and sex appeal: hoodies sculpted into mini dresses, pinstriped suits with peaked shoulders, and briefcases you can tote to the office and the club. They're pieces you'd see on a downtown dance floor or an enviably cool passerby. "My creative process starts from observing the day-to-day life wherever I am," says Lopez, who also co-founded the cult favorite Hood By Air in 2005.

"When I'm in Paris, New York, or the Dominican Republic, I'm always watching my family and people on the street." He adds that humanity will always be the heartbeat of his work: "[I'm inspired by] people. So long as I'm inspired by the world around me, I'll continue to create."

While one finger stays firmly on the pulse, Lopez keeps the rest of his hand hard at work in the studio. "My team and I send styles for revisions every season to try and perfect our silhouette. The Ana has been tweaked and revised to extend its longevity," he says, referencing the brand's signature circular top-handle bag that won him the CFDA's Accessory Designer of the Year Award in 2022. Lopez cares deeply for his customers—and their closets—and honors them in the best way he knows how: in an endless quest for excellence.

Matthew Harris, Mateo New York

"What truly inspires me to create is the belief that everyone, rich or poor, should have great personal jewelry," says Matthew "Mateo" Harris. "I grew up in Jamaica, and I remember my parents always ensured that I had great jewelry, no matter how simple or small the pieces were." It's somewhat of a subversive tenet; as an industry sect, fine jewelry is famously exclusive. But Harris is here to shake things up.

Harris taught himself design by studying YouTube videos and spending hours in New York City's diamond district, before launching Mateo New York in 2009. "I set out to create affordable great personal jewelry that people can cherish and wear daily," he says. His jewelry ranges from $200 to $2,000 and is timeless with a touch of quirk: chunky, baroque pearl pendants, distinctive gold bands cut in a Y-shaped silhouette, and diamond studs shaped like water droplets.

His talismans are ones you'll treasure for years to come. "Fine jewelry should last a very long time and be passed on from generation to generation. The only way to truly ensure a piece's durability is by setting up a great infrastructure for it to be repaired or refreshed over time," says the Montego Bay-born artist. For Harris, that means a design process that's beyond thorough: "My team and I create a digital drawing, then make a wax model of the piece. The wax is then cast into solid gold and polished, the diamonds are hand-set, and the pearls are fixed. A rigorous quality-control process is then done to ensure all is well," he says.

It's evident that Harris, who grew up watching his mother work as a seamstress, inherited her devout attention to detail.

Emme Parsons, Emme Parsons

Before launching her eponymous footwear line in 2017, Emme Parsons had never made a shoe in her life. Her career began in graphic design, with Parsons working as an art director for a handful of years. But she had a plan: Borrowing from her experience in visual design, she'd launch a footwear label of silhouettes that merge the classic with the contemporary. It would be minimalistic in the literal "less is more" sense. "At times, it feels like there's too much product out here," she says. Her brand would prioritize function and form over flash and make capital-G Good shoes.

To say Parsons has accomplished that initial goal would be an understatement—transcended would be far more accurate. Her brand, which she describes as "rooted in American modernism and balanced by European heritage," produces small-batch collections in Tuscan factories and uses materials like bio-based suede and vegetable-tanned calfskin leather. Signatures like flat, strappy sandals and easy-to-walk-in kitten heels have helped Parsons find a devout following in consumers who like easy, everyday silhouettes with a no-nonsense sensibility.

"My approach to creativity [is] much more pragmatic," says Parsons, who is based in Palm Beach, Florida. "A lot of time is spent thinking about the women I know: what they want to wear and how they want to feel." Forget a statement shoe for a once-in-a-blue-moon party—Parsons makes shoes you'll have in your daily rotation. "Quality and optimal comfort are the most important things we can offer our customers, along with intellectual but wearable designs," she says.

For those still struggling to sift through the deluge of options on the market, Parsons ends with a bit of advice: Look first at your closet. "Someone once told me the best designers are also the best editors, and I think that's very true. A sense of overwhelm and fatigue can be alleviated by a tightly edited, curated wardrobe."

Emily Adams Bode Aujla, Bode

Emily Adams Bode Aujla is familiar with the feeling of anemoia—nostalgia for a past you've never known. A graduate of Parsons School of Design and Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, where she simultaneously studied menswear design and philosophy, the artist has an appreciation for histories beyond her time.

She launched Bode in 2016, initially as a men's brand, later expanding to a women's collection in 2023, to conserve the beauty of yesterday and ensure it will live anew in tomorrow. More specifically, to "reinvigorate and preserve narratives, techniques, and histories that are in jeopardy of being forgotten due to advances in technological production," says the two-time winner of the CFDA Menswear Designer of the Year Award.

Bode Aujla, who grew up scouring antique stores, fairs, and vintage markets in Atlanta, Georgia, makes small-batch clothing that tells a story—not just in its appearance but in the how, when, and where of its creation. She refashions antique quilts into outerwear and turns 18th-century Portuguese grain sacks into shirting. Recent Bode collections feature deadstock wool sourced from a tailor in Buffalo, New York, who closed his business back in the 1970s, and vintage buttons from Muscatine, Iowa, which produced one-third of the world’s pearl buttons in the early 1900s from clamshells caught in the Mississippi River. Her take on upcycling is deep and tender. Rather than simply shy away from the context of the previous edition, Bode Aujla spotlights it. "It is a great hope of Bode's to prioritize craftsmanship [and] preservation through the sharing of knowledge," she says.

There's an inherent, albeit subtle, political undertone in her work, too. As the first female designer to show at NYFW: Men's, her interest lies in "largely female-centric craft techniques" and "personal narratives and crafts predominantly made by and for the domestic space." Bode Aujla reinterprets the concept of a "woman's touch" to be both respectful and insurgent: honoring those who came before her while simultaneously opening up her gender-bending brand to anyone who wants in.

Henry Zankov, Zankov

Henry Zankov is well aware of the long-standing traditions of knitwear. As the St. Petersburg-born designer describes, it’s a category "rooted in craft and with a particular savoir-faire." He just prefers chucking the rule book out the window. "Pushing the boundaries of what knitwear looks like is exciting to me," Zankov says. "The idea that a single fiber can be transformed into yarn, and then a garment can be knit on a special machine with a unique stitch, is extraordinary. The possibilities," the FIT graduate adds, "are endless."

Zankov's eponymous brand reflects his boundless enthusiasm: Pieces feature geometric, Piet Mondrian-esque prints, open weaves flecked with sequins, and cheeky cutouts that hit at the hip. If optimism was a sweater, Zankov would have made it. The designer, who honed his knitwear talent at Diane von Furstenberg and EDUN, credits an open-minded attitude for influencing his joie-de-vivre approach. "For me, it is about being curious," he says. "To be creative, you have to trust that this information will come to you in unexpected ways."

While Zankov's approach to design is playful—perhaps even rebellious—it’s equally as rigorous and detailed. "If an item of clothing is well designed and resolved, this, to me, is a sign of true quality," says the Russian-American designer. Unsurprisingly, he's optimistic that fashion is heading in a direction that celebrates intention, both in its design and consumption. "We, as a society, are going through a big change and craving more intimacy with how we consume and with what we wear—and craftsmanship naturally evokes this idea of finding intimacy with clothing."

Christopher John Rogers, Christopher John Rogers

Candy-buffet color palettes, souped-up sleeves, and kaleidoscopic prints are common codes in the house of Christopher John Rogers. His work, while decidedly not shy, is earnest and sincere all the same. It's loud—but intentionally so, because the American designer is serious with what he has to say: Rogers makes clothes for expressive folks who rebuke the idea of "effortlessness." The CJR customer cares a lot. Her style is an unapologetic, considered performance. As the brand's ethos states, it's "directed towards an individual with a strong sense of self."

The Baton Rouge, Louisiana-born designer ensures his spirited pieces never go full-tilt costume by grounding them in careful construction. A corseted LBD sits sharply on the body thanks to its precise rainbow piping, and a floral-print puffball skirt stays structured with a pannier-style waist. Look also to the crowning jewel of his brand’s Resort 2024 collection: a blue cotton twill bow blouse that's woven to be a supersized replica of the decoration that sits on your presents.

Per the brand, Rogers "[delivers] clothing with an emphasis on quality manufacturing and timeless appeal, whilst encouraging our customer to take up space." In doing so, he has captured the hearts of bona fide maximalists everywhere, creating a devout following among the boldest of the bold—and, when dressed in small doses, for curious minimalists stepping out of their comfort zones.

Amy Zurek, Savette

Making a highly coveted handbag is a matter of alchemy. There is some semblance of a formula to follow (a trendy shape plus a recognizable logo equals dollar signs), but to truly and consistently crack the code, you need a bit of magic. Amy Zurek knows this better than most. She cut her teeth as a handbag designer and consultant working for The Row, Coach, and Khaite, until venturing out solo to launch her bag brand in 2020.

"Savette was born out of my desire to fill in the gaps that I saw in the market—bags that were both clean and luxurious, neither boring nor overtly branded," Zurek says. Here's where the magic of handbag design comes in: you must accurately anticipate what shoppers want—often before they themselves even know what their handbag-loving hearts desire. Zurek knew that by focusing on architecturally sound, pure-and-simple good design, Savette would succeed.

"Each bag may look simple, but the construction is anything but. With up to 60 individual components in a bag, the way the pieces fit together is a critical element of the creative process," explains Zurek, who studied fine art and art history at the University of Pennsylvania and then fashion design at Parsons School of Design.

She works with a team of artisans outside of Florence, Italy, and considers every inch and stitch of her handbags. It's this attention to detail, says the New Yorker, that sets Savette apart from the rest. "Knowing the hand touch that goes into each bag is something that matters to consumers, who are smarter and savvier than ever before."

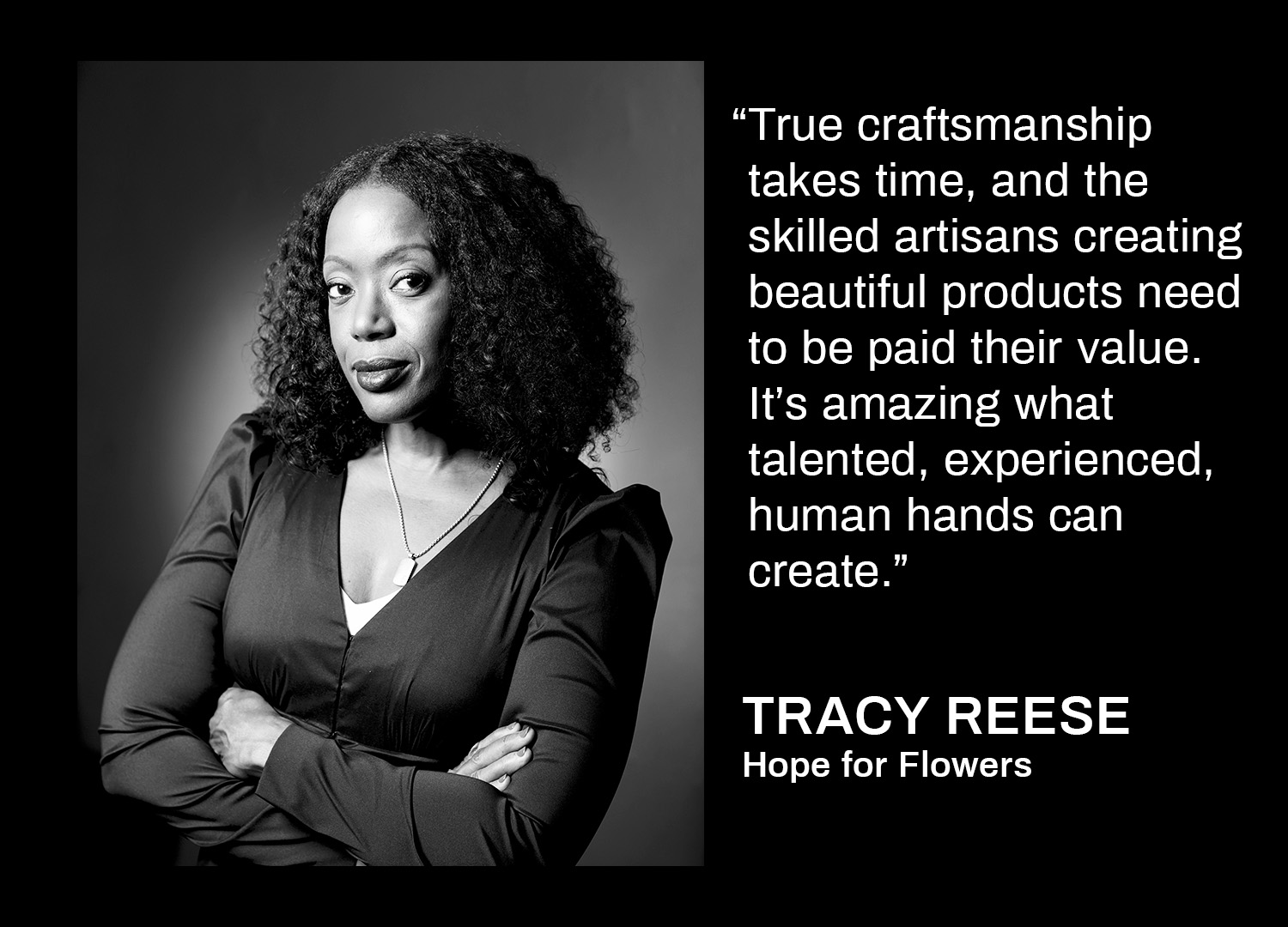

Tracy Reese, Hope for Flowers

Tracy Reese's list of accolades is overwhelmingly impressive. She's sat on the Council of Fashion Designers of America board of directors since 2010, meaning she's likely played a role in helping your new favorite fashion designer become your new favorite fashion designer. Michelle Obama and Oprah Winfrey are fans. Her now-shuttered self-titled label was so prolific it spawned three sub-brands, Plenty, Frock!, and Black Label. Then, perhaps most impressive of all: In 2019, after over 30 years in New York City, Reese moved back to her hometown of Detroit to do it all over again.

She launched Hope for Flowers, a fashion brand based out of Michigan, which offers eye-catching environmentally conscious clothing—think floral magenta gowns woven from plant-based fibers and puff-sleeved blouses adorned with akoya shell buttons. "We want the clothes to have an emotional impact that will inspire customers to purchase but feel accessible," Reese says. "[Designing] is a lot like putting a complex puzzle together, interweaving dreams with reality. Can our inspiration shine through in clothing that is designed to be useful in the lives of modern women?"

With Hope for Flowers, Reese encourages shoppers to cultivate a connection with their closets. "The buying public's addiction to fast fashion and throwaway culture makes a future for craftsmanship difficult. True craftsmanship takes time, and the skilled artisans creating beautiful products need to be paid their value," she says. "It's amazing what talented, experienced, human hands can create."

Peter Do, Peter Do and Helmut Lang

Who is Peter Do? The elusive designer, whose personal uniform consists of an anonymous hoodie, pulled-down baseball cap, and face mask, gets this question a lot. His resumé offers insight: He's a FIT grad, co-winner of the 2020 LVMH Prize, and an alum of Celine from its Phoebe Philo, l'accent aigu days. Do launched his self-titled brand in 2019 and is currently creative director at Helmut Lang. People call the Vietnamese designer a prodigy. But the best way to acquaint yourself with Do is through his work.

His clothes are androgynous cocktails that live beyond a box or binary. Sharp tailoring and understated sexiness are central to his designs: His eponymous brand's now-signature backless suit epitomizes both themes. Do adores high-quality wardrobe basics, as seen in his Helmut Lang debut filled with white poplin button-downs, razor-sharp trousers, and black blazers that fit just right.

He's also strongly against cutting corners. "We have a button-up shirt that we've been working on for years, that I'm finally beginning to love more—although it's not quite at 100 percent yet," the designer wrote in the show notes of Peter Do Spring/Summer 2023. "The hand-done special techniques that we used throughout the collection—from resin dye, bleach, and paint, to print, studs, and embellishment—are some of the most labor-intensive processes in garment making." He's deeply devoted to the processes behind his work, as "it reinforces [his brand’s] stance on believing in slow fashion that isn't trend- or hype-driven."

So, who is he? Do is a designer who appreciates the spectacle of simple, exquisite clothes—and he's damn good at making them.