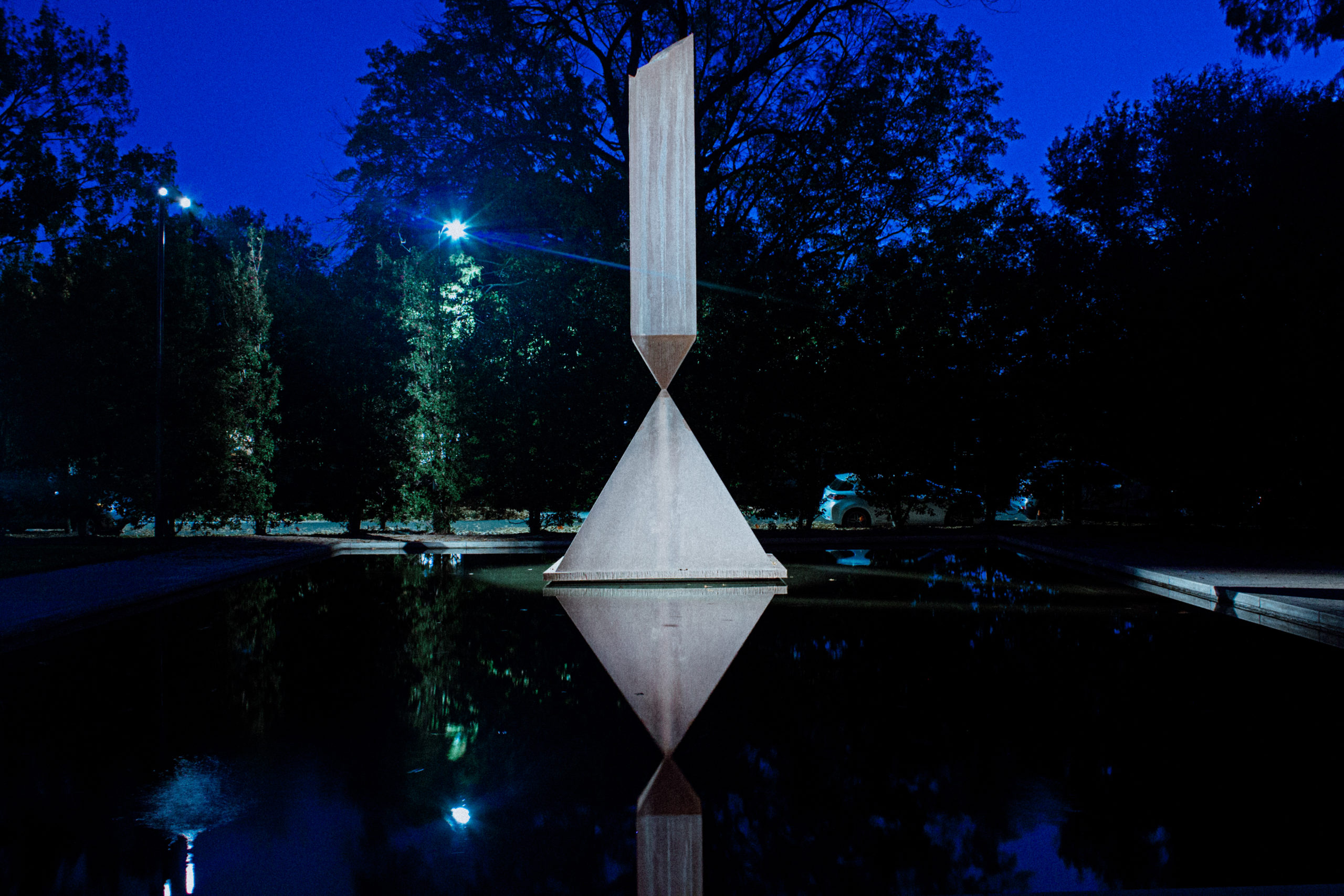

In a part of Houston famous for its giant live oaks, museums, and million-dollar homes, 3900 Yupon Street looks out of place. With its bland brown brick facade, it could be just another building that schoolchildren throw balls against during recess. But the Rothko Chapel—next to a stone pyramid sculpture balancing a broken obelisk at its apex—has inspired both bewilderment and meditation in its visitors for more than 50 years.

Outside the chapel, dusk had hit the humid city. Inside, the crowd sat, prayed, and cried. The occasion was an event titled “A Time of Remembrance.” Fifty or so visitors contemplated cycles of life and death in one short hour on November 2.

Open to the general public, the gathering included reflections by hospice workers, a Vedic priest, and a poet, as well as musical performances by a guitarist and a music therapy group from nearby Rice University.

The chapel is a non-denominational place of worship and the permanent home to a world-famous set of canvases created by Mark Rothko. Born Marcus Rotkovitch, the Latvian-American abstract painter of the post-war era known for his color field paintings never saw the chapel’s completion or its use as a spiritual space and forum for world leaders like the Dalai Lama, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, and former President Jimmy Carter. But an estimated 100,000 people experience it every year. “It” isn’t the fact that you’re sitting next to paintings by a man whose works regularly sell for upward of $50 million. “It” is the quiet, the awe, and the reverie.

That the event was taking place on the second half of Día de los Muertos and a day after All Saint’s Day was no coincidence. The Mexican holiday celebrates the return of departed souls to the land of the living with parties, bright colors, and marigolds. All Saints’ Day honors saints, known and unknown. Held during National Hospice and Palliative Care Month, the event honored those who deal so often with death—nurses, home care aides, therapists, and social workers—and those who are mourning.

Diana X. Muñiz, a chaplain with Bayou City Hospice, said that remembering those who have died is a moral duty, not just an exercise. She also referenced Dutch Catholic priest and author Henri Nouwen.

“Is it possible to befriend our dying gradually and live open to it, trusting that we have nothing to fear?” Nouwen wrote in his book titled Our Greatest Gift: A Meditation on Dying and Caring. “Is it possible to prepare for our death with the same attentiveness that our parents had in preparing for our birth? Can we wait for our death as for a friend who wants to welcome us home?”

Juan R. Palomo, a retired Houston journalist and current poet, spoke about the failure of the ego to accept the circumstance of death. He wondered aloud about his legacy and whether he will be remembered. Is that a selfish or egotistical thought? he asked. Well, yes. “I am a human being, after all,” he said. He read from his poem “Las Tres Muertes,” or the three deaths, which refers to the final breath, the burial, and the last time someone utters your name.

He read a poem about an older brother who died before Palomo was born. The poet and his surviving siblings “cling to the sepia print of you staring down the camera. We hold onto blurred stories—faded second-hand memories patched together from others’ washed out recuerdos.”

Then, the community remembrance ritual began. Jesus Lozano, an avuncular, pony-tailed Houston Independent School District music teacher, played the somber ballad “La Llorona” in Spanish on the guitar.

When he began, the altar for the ofrenda—a small mahogany coffee table—stood bare in the middle of the chapel. For a few minutes, no one budged. Then, slow to stand but determined once moving, an elderly woman rose through the song’s chorus and placed a memento. With that, a tide followed. Attendees placed photos, trinkets, and letters—one with a sketch of an oak tree, another with the mark a of kiss—in remembrance. One woman took off her left earring and pinned it to her card. Another dropped a dark purple rose, the same hue as Rothko’s works that encircled us.

All the while, Lozano’s guitar ballads continued. The next song, Lozano’s rendition of “Amor Eterno” by Juan Gabriel, began: “Tú eres la tristeza de mis ojos que lloran en silencio por tu amor,” he sang. You are the sadness of my eyes that cry in silence for your love.

And in the chapel, people cried.

Around us on walls a few shades darker than bone hung 14 large canvases of deep purple. Dominique de Menil, who with her husband commissioned the chapel and its art, once wrote that “his colors became darker and darker, as if he were bringing us to the threshold of transcendence, the mystery of the cosmos, the tragic mystery of our perishable condition,” according to a book by author Annie Cohen-Solal.

From where I was sitting, the brushstrokes were Turkish coffee grounds, abstract and imperfect enough to permit interpretation. Up close, they disappeared. At that time of evening, they didn’t show as much nuance as they do under the daylight that comes through the geometric skylight of octagons, triangles, and rectangles.

From where I was sitting, the brushstrokes were Turkish coffee grounds, abstract and imperfect enough to permit interpretation. Up close, they disappeared.

After Lozano strummed his final chords, a bereavement counselor read aloud “We Remember Them,” a Jewish call-and-response poem. “At the rising of the sun and as it’s going down,” she said. “We remember them,” the chapel echoed. “At the blowing of the wind and in the chill of winter”; “At the opening of the buds and in the rebirth of spring”; “When we are weary and in need of strength”; “When we are lost and sick at heart”; “We remember them.”

The program concluded with a moment of silence. I find these all start the same. Noticing the hum of air conditioning. The rustling of sleeves and shuffling of shoes on the floor. The repositioning of bums in seats. Men evacuating their throats of stray particles. Someone getting a hurried cough out of the way before the quiet gets too loud and, perhaps for some, too uncomfortable. But then, collectively, the silence is made. And for brief moments—only in spurts because we are human beings, after all—you realize you’re in a room with dozens of people and not a sound is being made. A harmony of nonexistent notes produces a feeling of pleasure. On that day, I tried to control my breath going in and out, the small twitches of my body. Because to break the silence we’d made together would have been to destroy something beautiful.

“Of course, the artist must have sufficient means at his command to achieve his objective so that his work becomes convincingly communicative,” Rothko wrote roughly 30 years before his work on the chapel finished. “But clearly it is something else which the art must communicate more than this before its author is seated among the immortals.”

As Palomo had said earlier, “The quest for immortality is part of being human.”

In Rothko’s chapel, it seems, Rothko found that “something else which the art must communicate.” Gathered before his canvases the color of bruised flesh, participants that day found “it” through silence as much as through words and music—in a chapel that embodies the beauty and power of abstract expressionist art, of contemplation. A temple with no iconography, no reference, no suggestion of anything explicitly divine.

Rothko died by his own hand, never seeing the realization of his vision. A year before Rothko’s suicide, writer and art critic Dore Ashton visited him in New York City. He was “wearing slippers and he shuffled, with a vagueness to his gait that I attributed to drinking. … His face, thin now, is deeply disturbed, the eyes joyless. He wanders. He is restless (he always was, but now it is frantic),” she recounted in Cohen-Solal’s Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel.

Somewhere in that chapel—perhaps on one of the wooden benches, or in a corner of the room, or maybe inside one of those supernatural paintings—is Rothko’s seat among the immortals.