On October 13 one of Australia’s largest medical insurers, Medibank, announced it had suffered a cyberattack – one which has resulted in the breached personal details of 9.7 million customers in Australia. We now know the hackers, who are almost certainly Russian, demanded a ransom of US$9.7 million (about A$15 million) – or else they would leak the data on the dark web.

It’s believed the hackers are linked to the notorious REvil cyber gang which, according to Russian sources, was allegedly dismantled and arrested earlier this year.

The Medibank breach consists of an alleged 200GB of data that contain personally identifiable information such as names, dates of birth, addresses, phone numbers, Medicare numbers, credit card details, and ID documents. Importantly, it also contains sensitive personal information about medical diagnoses and procedures covered by Medibank and ahm health insurance.

Medibank did not have a cyber insurance plan, and so decided it would not pay the ransom. This choice is consistent with Australian government recommendations.

The deadline to pay was around midnight on Tuesday. With no ransom received, the hackers kept their promise and the first batch of data was released in the early hours of Wednesday, November 9.

This breach comes with clear risks, and a lot of people will understandably be concerned. Here’s what to know if your data have been exposed, or is exposed in the coming days.

Read more: Medibank won't pay hackers ransom. Is it the right choice?

What has been leaked so far?

Here’s what the hacker group divulged in the first batch of leaked data:

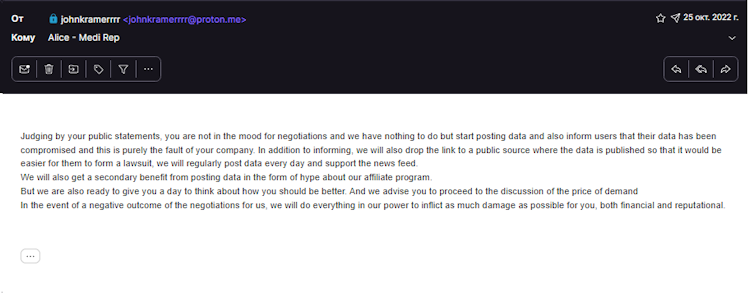

screenshots of failed negotiations with Medibank

a list of Medibank employees, with their full names, work emails, details of the mobile phones and computers they use, as well as some home wifi names (which can be used to find a person’s home address)

the personally identifiable information (including what appear to be passport numbers) of more than 500,000 international students, either currently or formerly in Australia

the personally identifiable information (including what appear to be ID document numbers) of an additional 500,000 people

and the personal information (including addresses and phone numbers) of 200 people. Most concerningly, this includes details of medical diagnoses and procedures, and a “naughty list” of 100 people singled-out for having medical diagnoses of psychological disorders and drug addiction.

On the following day, November 10, the hackers released an additional 300 records of personally identifying information on account holders who had abortions charged against their accounts.

How might criminals use the stolen data?

Blackmail, fraud, identity theft and targeted scams are the three most obvious options for the hackers now in possession of Medibank customers’ data.

Personal information and information about medical treatments considered “controversial” – such as treatments related to sexual health, mental health, and addiction – could be used to blackmail victims, including high profile people and foreign nationals.

Foreign nationals may be particularly vulnerable if they have undergone procedures considered socially unacceptable – or even illegal – in their home country. This could even make it dangerous for them to return.

Personally identifying information, such as ID documents and contact details, may be used to impersonate victims and seize financial accounts, open lines of credit, or impersonate a victim to extort their friends and family for money.

Personal information can also be used to carry out targeted scams. For instance, cybercriminals may target data breach victims with highly personalised – and therefore highly believable – phishing attacks.

There are also data recovery scams, in which scammers contact victims and make the impossible claim to remove their data from the internet for a fee.

What to do if you’re targeted

We don’t yet know of every single individual who has been directly affected by this breach. Medibank will need to notify individual customers that have been affected, and has said it will continue to do so.

However, concerned customers can take some pro-active steps, such as securing critical accounts and being aware of potential scams – as we describe above, and also as we described in relation to the Optus breach previously.

Read more: What does the Optus data breach mean for you and how can you protect yourself? A step-by-step guide

While passports and drivers licenses can be replaced, there’s no protection against your medical history being released to the public. Hackers may try to exploit this information in extortion scams.

If you are targeted for an extortion scam as a result of the leak, you should notify law enforcement immediately, either through ReportCyber or your local police office. There won’t be any hiding of information that is already posted online, and these criminals can’t keep it a secret for you, no matter what they promise.

If you receive a text or email from scammers related to your medical history, do not reply as it will only encourage them to harass you further.

What do we expect to happen next?

So far, the hackers have released less than 1GB of the 200GB allegedly stolen, with already serious consequences for more than a million Australians. But this is just the tip of the iceberg.

The communications leaked by the hacking group suggest two things. First, they appear to still be trying to extort their US$9.7 million ransom from Medibank. This explains the trickling release of data, rather than all of it being leaked at once.

Second, they seem intent on releasing the data if Medibank does not pay. Their own stated reason for releasing the data is to market their “ransomware as a service” offerings to other cybercriminals. This is when an initial hacker first gains access to a company, and then hires a hacking group such as REvil to actually run the complicated ransomware scheme – a service made (in)famous by REvil.

It seems unlikely Medibank will (or should) pay the ransom, and likely the unnamed ransomware gang will release the entire dataset to the public.

Should that happen, we may be facing an unprecedented exposure of personally identifiable information with potentially 9.7 million identity documents and credit card details stolen.

This possibility dwarfs even the worst case scenarios of the recent Optus breach, and will require an unprecedented effort to update and secure the identity documents and credit card details of those affected.

Read more: Why are there so many data breaches? A growing industry of criminals is brokering in stolen data

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.