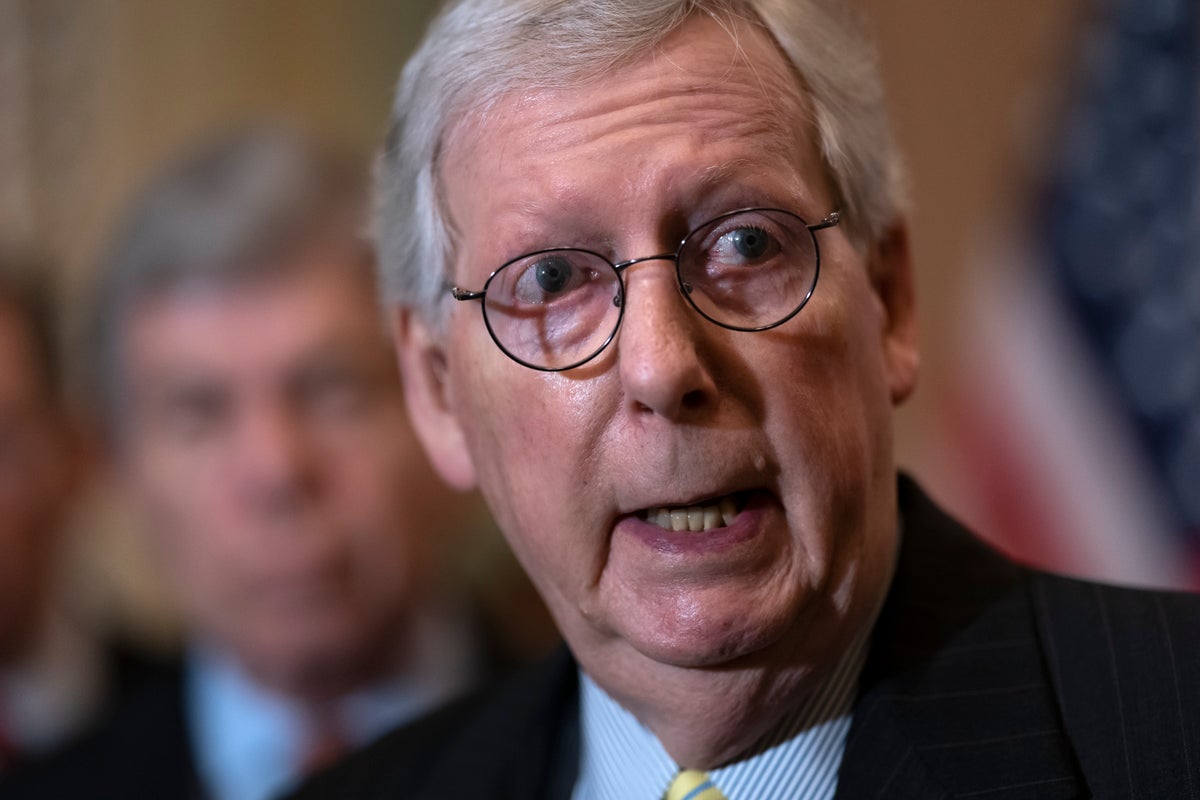

Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell threatened Thursday to derail a bill designed to boost semiconductor manufacturing in the United States if Democrats revive their stalled climate and social policy package.

The rejuvenation of the Democratic reconciliation package, central to President Joe Biden's agenda, remains a work in progress and is far from certain. But with some signs of progress in the negotiations, McConnell is moving to complicate Democratic plans by warning that Republicans would react by stopping separate semiconductor legislation from moving over the finish line in the coming weeks, despite its bipartisan support.

“Let me be perfectly clear: there will be no bipartisan USICA as long as Democrats are pursuing a partisan reconciliation bill," McConnell tweeted, referring to the shorthand name for the computer chips bill that passed the Senate last year.

Both chambers of Congress have passed their versions of the legislation, which would include $52 billion in incentives for companies to locate chip manufacturing plants in the U.S. Lawmakers are now trying to reconcile the considerable differences between the two bills, but at a pace that has many supporters worried the job won't get done before lawmakers break for their August recess.

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said McConnell was “holding hostage" a bipartisan package that would lower the cost of countless products that rely on semiconductors and would yield hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs.

“Senate Republicans are literally choosing to help China out compete the U.S. in order to protect big drug companies," Jean-Pierre said. “This takes loyalty to special interests over working Americans to a new and shocking height. We are not going to back down in the face of this outrageous threat."

Democrats have eyed using reconciliation — a special budget process — to pass parts of their agenda through the 50-50 Senate because it allows them to circumvent the filibuster and pass legislation with a simple majority. It was anticipated that any new reconciliation package Democrats pursue would include provisions designed to lower drug prices for many consumers.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. and Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., have been talking intermittently for months in an effort to craft a whittled-down version of the massive environment and social program measure that Manchin killed in December.

As part of that drive, Democrats are expected to submit language reducing prescription drug costs to the chamber’s parliamentarian in coming days, according to an official familiar with the process.

The parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, must affirm that the provisions adhere to Senate rules. That would allow Democrats to use special procedures that would let them approve the legislation in the 50-50 chamber over unanimous Republican opposition.

The prescription drug provisions would be crucial to the bill because they could produce hundreds of billions of dollars in savings by reducing federal costs.

Those savings would be used to pay for other initiatives under discussion dealing with climate, energy and possibly health care subsidies for low earners. Schumer and Manchin have yet to reach agreement on other potential parts of the bill, which Schumer is hoping the Senate would consider as early as late July.

The prescription drug provisions would let Medicare begin negotiating prices for the drugs it buys from manufacturers next year and increase federal subsidies for premiums and co-pays for some low-income people, according to a summary obtained by The Associated Press.

It would also cap Medicare recipients’ out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 annually, payable in monthly installments; make it harder for pharmaceutical companies to raise prices by requiring them to provide rebates if the cost exceeds inflation and make vaccines free for Medicare beneficiaries, the outline said.

The now defunct version of the legislation would have cost around $2 trillion over a decade and had cleared the House. But Manchin, who had negotiated with party leaders for months and whose vote Democrats needed for passage, abruptly said he was opposing it, arguing it would have fueled inflation.

Some Democrats have expressed optimism that the effort can be revived. Others have expressed pessimism that a fresh, election-year agreement with the West Virginian can be reached as the Senate calendar dwindles.

“To his credit, Senator Schumer is much more optimistic than myself,” No. 2 Senate Democratic leader Richard Durbin of Illinois told reporters Thursday in Madrid, where Biden and lawmakers were attending a NATO summit. “So perhaps before the end of the year, they’ll deliver this miraculous bill, but I’m going to continue to work in the 60-vote environment.”

That was a reference to the 60 votes, including support from at least 10 Republicans, that major legislation usually needs to pass the Senate.

The semiconductor legislation will need support from at least 10 Republicans in the Senate, and possibly more, to get a bill to Biden's desk to be signed into law. If McConnell withholds his support, it makes the task much harder, if not impossible, as other GOP lawmakers follow his lead.

Supporters of the semiconductor legislation include the nation's auto makers and the nation's biggest tech companies. They have ramped up their lobbying in recent weeks to congressional leaders, saying the bill's provisions boosting investments in research, workforce development and domestic manufacturing are critical if the U.S. wants to compete with other nations, particularly China.

McConnell met with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Schumer on the semiconductor legislation a little more than a week ago. The two Democrats emerged from the meeting saying that negotiators should “work with the urgency the situation deserves." They also said they expressed their belief to McConnell that there was no reason the bill couldn't pass in July.