Martin Amis, the celebrated enfant terrible of British books, a man whose gift for piercing prose and razor-sharp observational comedy lit up the literary scene, has died at his home in Florida at the age of 73.

The author, who had oesophageal cancer, wrote 15 novels, four short story collections, two screenplays and seven books of non-fiction, including his 2000 memoir Experience, which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for biography and which, in part, deals with the murder of his cousin Lucy Partington by serial killer Fred West.

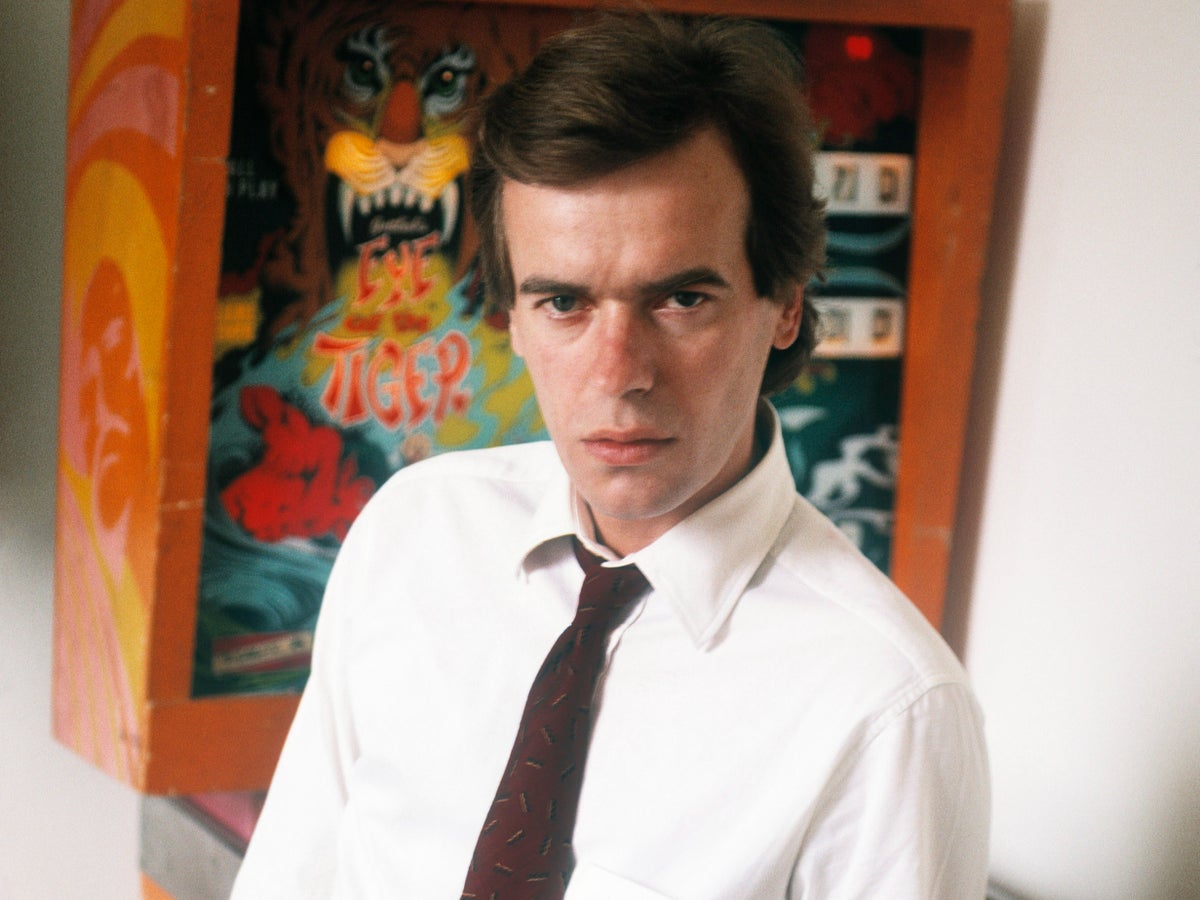

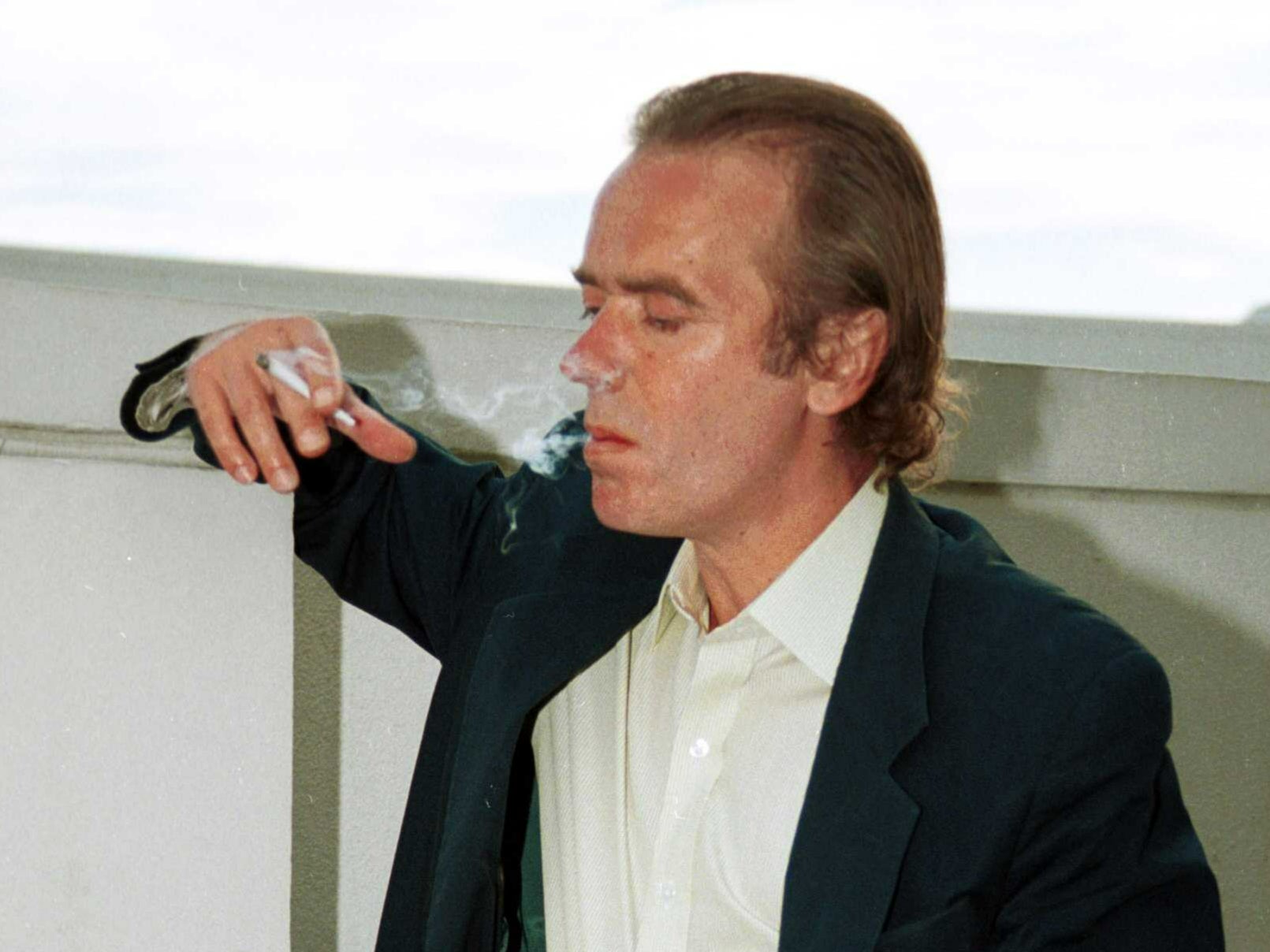

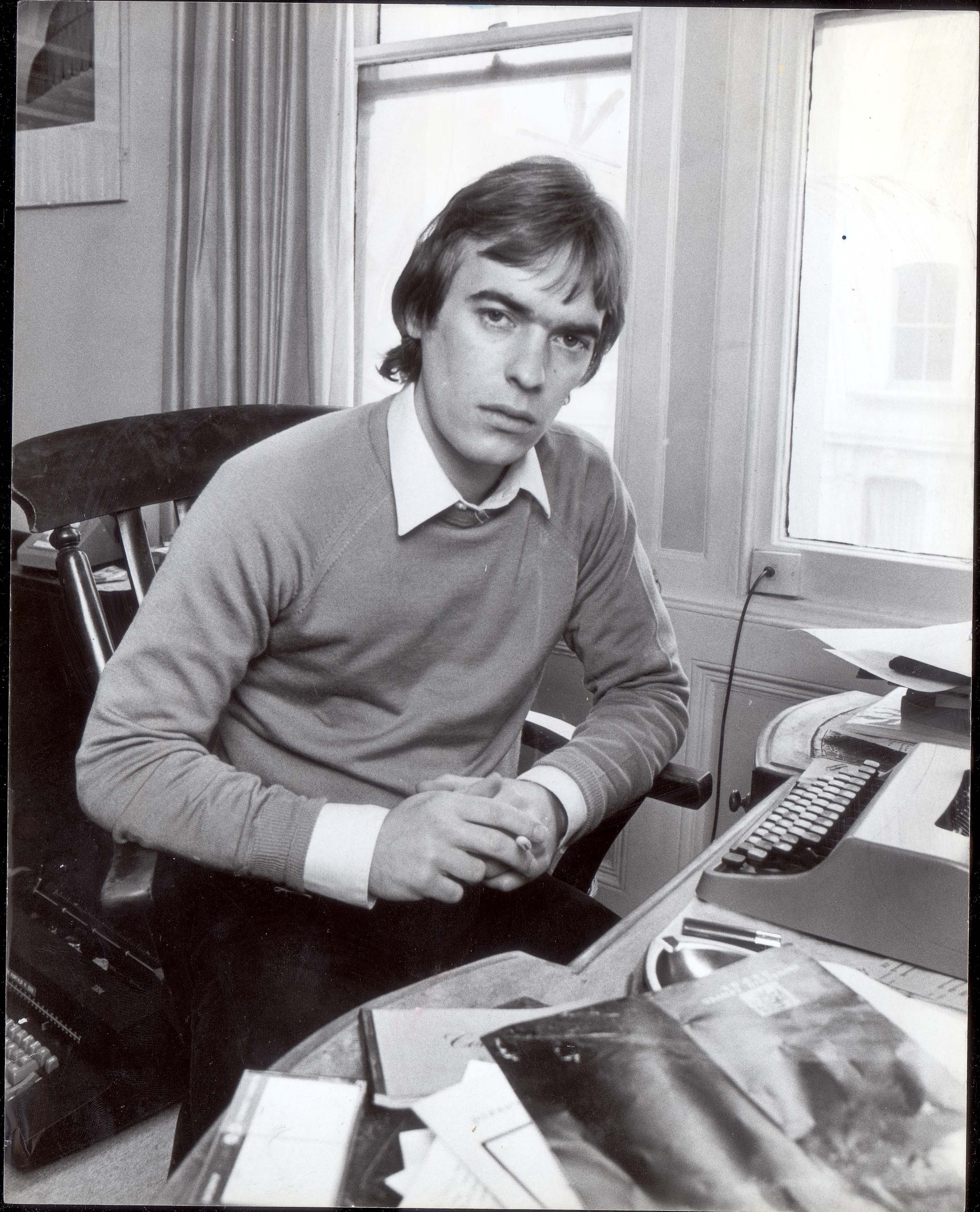

The lasting image of Amis is the young, louche literary celebrity, cigarette dangling from his ample lips, and it is no coincidence that he was widely dubbed “the Mick Jagger of fiction”. Amis, who was born on 25 August 1949 in Oxford, was the son of Sir Kingsley Amis, author of the comedy classic Lucky Jim and the Booker-winning The Old Devils. Amis junior came to regard the “literary curiosity” of his heredity as being “tainted”. “It became accepted that you could say whatever you f***ing well-liked about me – because, so to speak, I didn’t earn it,” he said in 2014.

Amis complained about the “vicious” press coverage that fuelled his reputation as the “the Bad Boy of English letters” and few modern English authors divided opinion as starkly as Amis, who delighted in writing about “disgraceful human beings”.

Being the son of a well-connected author was certainly no obstacle to his own career, nonetheless, he broke free from his father’s considerable literary shadow, starting with his first novel, 1973’s The Rachel Papers, written after he had gained a first in English Literature from Oxford University. It was a light-hearted autobiographical study of teenage desire, impressive enough to earn him the Somerset Maugham Award.

Amis later dismissed his debut as “crude and clumsy”, although his preoccupation with ways to snare women persisted. At 47, for Desert Island Discs, Amis selected saxophonist Ben Webster’s tune “Late Date” because it offered “a brisk way of seducing women… trying to jolly them along before they have a chance to think about it”. A love of jazz was inherited from his father: Amis named one novel Night Train, after pianist Oscar Peterson’s composition.

His colourful reputation as a ladies’ man fuelled the copious press coverage of his life. In 2007, Amis revealed his affair with Tina Brown, former editor of Tatler, the New Yorker and Vanity Fair, and credited her with transforming him into a “literary Mick Jagger”. Their romance began when he was 23 and she was an undergraduate at Oxford. He used to quote Philip Larkin’s poetry in bed, she recalled.

In 2009, former girlfriend, Julie Kavanagh, wrote about their past (with his consent) for the magazine Intelligent Life and paid tribute to his “Byronic magnetism”, admitting she had been bowled over by “the Jagger lips, moody monobrow and fag between two fingers”. She praised his gift for wit and irony. Writer Clive James also noted his “stubby, Jaggerish appearance”.

In 1976, Germaine Greer penned a 30,000-word love letter to Amis, a man who left her “helpless with desire”. Although the letter was never actually sent – and only came to light in 2015 when the feminist author’s archive to the University of Melbourne was opened up – it captures his appeal at the time. “It astonishes me with that tobacco hair and those tangled black eyelashes that you do not have brown eyes. Your eyes … are cool-coloured, sort of air force blue-grey, and strangely unreflecting. You slide them away from most things and look at people through your thick eyelids, under your hair, your eyebrows and your lashes. You look at mouths more than eyes. Is it because you hate to look up? It is very shy and graceful and tantalising, as well you know,” Greer wrote.

His many girlfriends included aristocrats and writers, although he stated in his memoir Inside Story that the early ones were mostly “blue-collar” and “international,” including “a Ceylonese, an Iranian, a Pakistani, three West Indians, and a mixed-race South African”.

Although he loved partying and romance, the 1970s was an era in which he was sharply focused on his writing career. After publishing Dead Babies in 1975 (a darkly witty parody of Agatha Christie), Amis worked for a spell as literary editor of The New Statesman. Two more acclaimed novels, 1978’s Success and 1981’s Other People, were followed by his greatest triumph, 1984’s Money: A Suicide Note. Amis wrote it in longhand, inspired by the simple idea of “a big fat guy in New York, trying to make a film”. The narrator, the alcoholic John Self, is loathsome; obsessed with celebrity, pornography, drugs and wealth.

Money is inventive, bold, bursting with wit and clever artifice. At his best, you sensed the unmistakable energy of Amis having fun while writing; part of the joke of Money was having a semi-literate narrator speaking in honed prose. It was a difficult book to write, Amis said, because it was essentially a plotless novel whose success depended on people accepting the satirical main voice. Amis would often point out the pitfalls of readers identifying with the protagonist instead of the author, yet it is telling that Money features a character with a walk-on part called Martin Amis – perhaps to distance himself from John Self.

Amis was full of contradictions: claiming that “sexism is like racism: we all feel such impulses” while also insisting he was “a feminist”. Money certainly appealed to men more than women. His female characters, such as Self’s girlfriend Selina (who is described as offering “the frank promise of brothelly knowhow”), were pretty one-dimensional. His fiction also had problematic aspects when it came to diversity. “Amis would never win a racial sensitivity award… until Lionel Asbo, Black characters in his novels are peripheral figures of fear or fun,” wrote former Booker judge Sameer Rahim.

His 1980 novel London Fields is an interesting dissection of self-delusion and amoral behaviour, written in a tricky “four voice” narrative structure, and it contains many burnished comic lines, such as “Keith didn’t look like a murderer. He looked like a murderer’s dog.” Yet the misanthropy is wearisome and the dialogue, from clichéd, cringeworthy “ordinary” Londoners, is jarring. Trish Shirt, played in the 2018 movie adaptation by Lily Cole, says of Keith Talent: “He comes round my owce. Eel ... bring me booze and that. To my owce. And use me like a toilet.” Amis, a man who carried his blended tobacco in a little leather pouch, admitted taking tips for speaking Cockney from reading the memoir of the gangster ‘Mad’ Frankie Fraser.

The 1991 novel Time’s Arrow: or the Nature of the Offence, the tale of a Nazi doctor told in reverse chronology, made the Booker shortlist but was criticised as a lightweight treatment of the Holocaust. Amis picked literary rivalry and “mid-life crisis” as themes of his next novel. By the time The Information came out in 1995, Amis was in the midst of his own fortysomething “convulsion” after his marriage to Antonia Phillips collapsed – he left her and their sons Louis and Jacob for writer and heiress Isabel Fonseca, a woman nine years younger – having also recently “discovered” a 19-year-old daughter, Delilah, the result of an affair with a married woman in 1974.

Amis’s parents divorced when he was 12, and he lamented the embarrassment of his father’s “promiscuous behaviour” being “in the papers”. When Amis “lost control of events”, the celebrity author had a target on his back. It is entirely possible that sour grapes were a factor in the blows aimed at his reputation. The insular literary world went into a frenzy when Amis ditched his longstanding agent Pat Kavanagh (prompting a feud between Amis and her husband Julian Barnes, once his close friend) in order to hire Andrew Wylie, an American known as The Jackal, to negotiate a reported $1m advance for The Information.

Spats with fellow authors remained a constant of Amis’s life. He dismissed South African author JM Coetzee as having “no talent”, yet took great exception at Tibor Fisher’s excoriating comments about 2003’s Yellow Dog. One of Amis’s most celebrated rows was with the acerbic American writer Gore Vidal. When Amis interviewed Vidal for The Observer, they fell out over Vidal’s demand for copy approval and insistence that Amis refer to him as “pansexual” rather than “homosexual”. In the end, Amis had his revenge with a memorable article that included a damning scalpel-like cutting paragraph in which he commented that “Vidal has removed pain from his own life, or narrowed it down to manageable areas; and it is one thing he cannot convincingly recreate in his own fiction. But his deeply competitive nature is still reassured to know that there is plenty of pain about.”

Amis was also a master stylist, whose use of punctuation was an art form in itself, one that laid the foundation for his zinging prose. Amis was a devotee of what he called “minimum elegance”, and said that when he was writing he was always conscious of precision, “subvocalising a sentence in your head until there’s nothing wrong with it”. It is telling that his 2001 anthology The War Against Cliché remains a well-thumbed book on the shelves of many critics and journalists.

It also has to be admitted that Amis was no stranger to self-aggrandisement – he once described a “five-hour read of me” as “the dream night” – but his wit was never far behind. When he was asked to describe the profession of writing, he replied: “Well, it is a sort of sedentary, carpet slippers, self-inspecting, nose-picking, arse-scratching kind of job, just you in your study and there is absolutely no way round that. So, anyone who is in it for worldly gains and razzmatazz I don’t think will get very far at all.”

For most people, Amis was an enlightening, entertaining guest at dinner parties, one who loved word games and risqué anecdotes; although a mature student colleague I knew in the mid-1980s sat next to Amis at one such function not long after she had been through a torrid labour and had to endure an hour of him telling her how producing a novel was “just like a difficult birth”.

He remained in the news in his later life. In 2007, he was forced to retract the “rather stupid suggestion” that “the Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order”. His proposal that “people who look like they’re from the Middle East or from Pakistan” had their freedoms curtailed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks and be subjected to “strip-searching and discriminatory stuff” prompted professor Terry Eagleton to liken Amis’s statements on Muslims to “the ramblings of a British National Party thug”.

Five years later, “needing a change”, Amis relocated from London to New York, after giving up a position teaching creative writing at Manchester University, a move that echoed his father’s teaching career. The decision came after harsh reviews for 2006’s House of Meetings (a novel set in Stalin-era Russia) and 2010’s The Pregnant Widow (based in a castle in Italy during the summer of 1970), a period when Amis seemed to be struggling for relevance. His 2012 novel Lionel Asbo: State of England, set in the fictional London working-class borough of Diston Town, was full of dreary caricature villains.

Manchester United fan Amis wrote about “soccer thugs” in his non-fiction work. Although his football journalism was sometimes pompous, I enjoyed his amusing writing about tennis, a game he played six times a week at his peak, when he claimed he was “like a warrior poet” on court. He also loved playing pinball and in a zestful article about snooker, he described himself as a “flair player”, confessing he was “inconsistent, foul-tempered, over-ambitious, graceless alike in victory and defeat”. One of the saving graces about Amis was a capacity for self-deprecation. He was conscious of his lack of stature – he was 5’6” – and joked that a compensation for being a “short arse” was that you got fewer back problems.

In 2017, Amis and Isabel – who had daughters Fernanda and Clio together – moved to Manhattan after a New Year’s Eve fire destroyed their £5.6m house in Brooklyn. In 2020, Amis, who excelled at literary criticism, published Inside Story: A Novel, a fragmentary memoir that deals with his relationship with his godfather Philip Larkin, Christopher Hitchens and Saul Bellow, whom he called the greatest American writer of all time.

Post-pandemic, Amis admitted to friends that he lost the old hunger to create fiction, a far cry from his twenties, when he boasted of a “constant daily urge to write”. Before his death, he was working intermittently on some “short fiction about race in the US”.

Amis said that posterity was “no bloody use to me”, adding that the only thing that mattered “is being read after your death”. Will younger readers give a toss about the sepia brouhaha over his personal life? I doubt it. Hopefully, many will discover the unique comic voice and ferocious, incisive wordplay of Amis in his pomp.