You've got a problem. You've had hit singles but you want to turn away from the pop and embrace the dark, go from sweet love to sticky, move from the meaning of love to the meaning of god. What are you going to do? Buy a sampler and four plane tickets to Berlin, that's what.

It's easy to see it in hindsight, of course, but Depeche Mode’s early- to late-'80s period was the band’s most important. This is when they turned the loss of main man Vince Clarke into the biggest, darkest positive, keeping elements of the synth sound that defined early recordings, but layering it into an all-new industrial electronic rock.

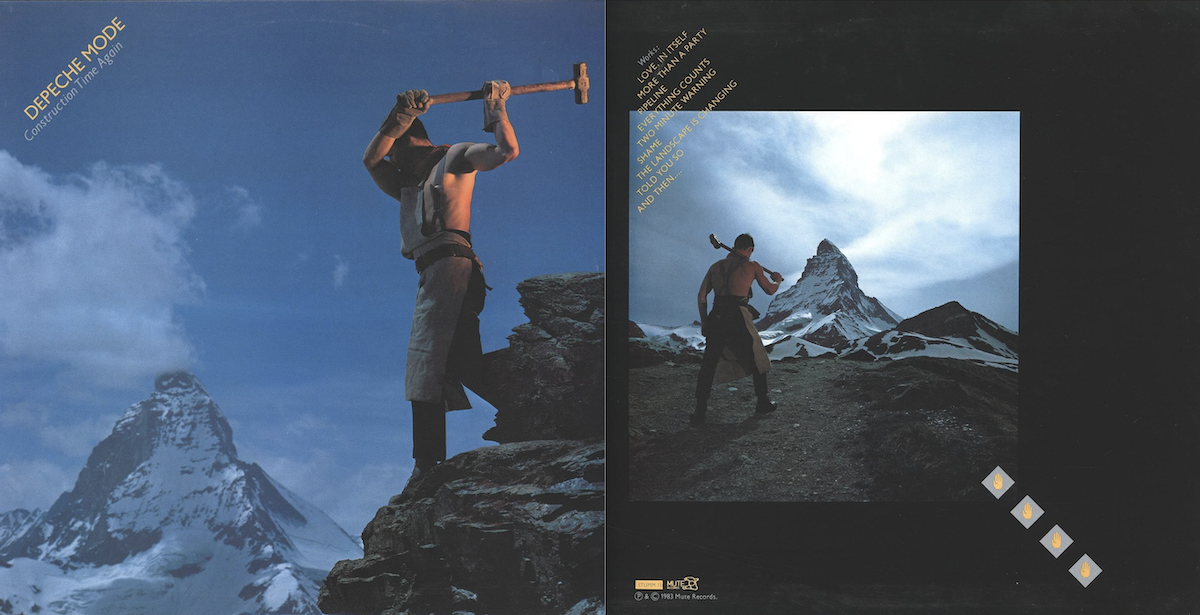

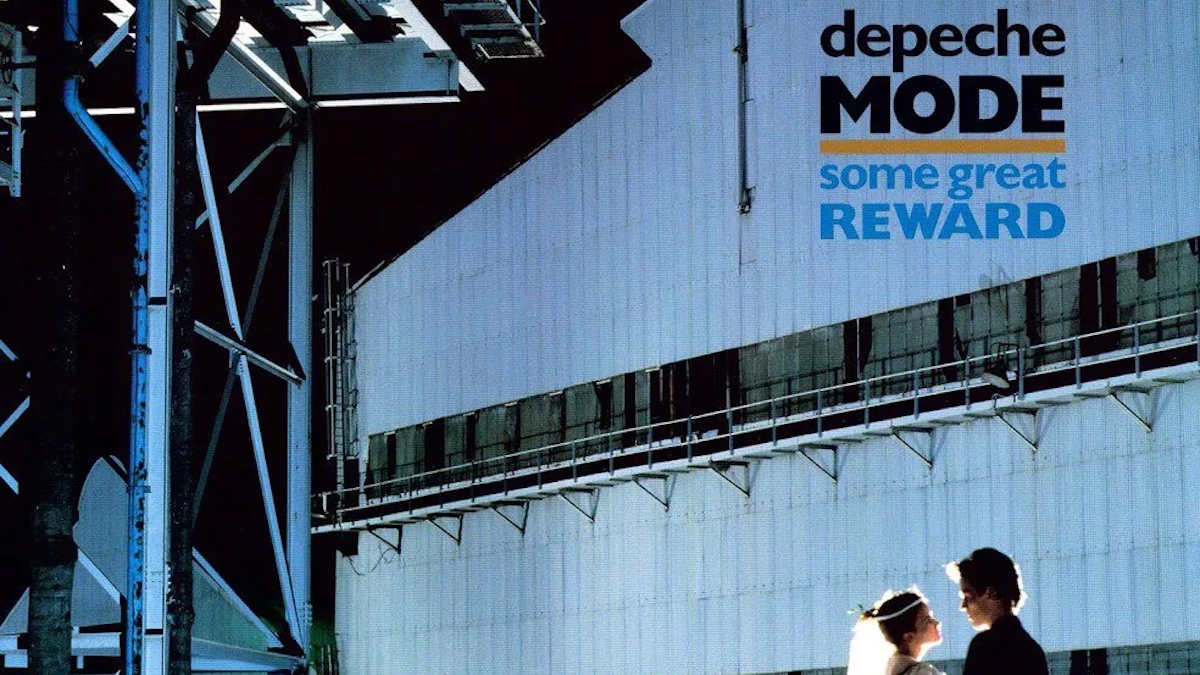

And they did it all over the space of three albums: Construction Time Again in 1983, through Some Great Reward 1984 and Black Celebration in 1986.

The Key Players

So many elements are responsible for this monumental shift in the Mode sound, but the core line-up of singers Dave Gahan and Martin Gore, the Vince replacement Alan Wilder and Andy Fletcher were, of course, at the centre of it.

There was Gahan’s newfound confidence both vocally and live, Gore’s maturing song-writing, Wilder’s musical abilities and willingness to experiment with the latest studio techniques and technology… Heck even Fletch – often derided for his lack of involvement in later years – was involved.

Much credit must also go to Mute label boss Daniel Miller for injecting a sense of evolution, and the enthusiastic and knowledgable engineer/producer Gareth Jones

But much credit must also go to Mute label boss Daniel Miller for injecting a sense of evolution into their recorded sound, and the enthusiastic and knowledgable engineer/producer Gareth Jones for helping them achieve whatever they wanted in the studio.

And maybe that studio was as important. Where David Bowie enjoyed so much of the recording of his seminal Berlin Trilogy at Hansa Tonstudio, it's a less well-known fact that Depeche Mode also made much of their run of three influential 80s albums there.

Bowie loved the studio for many reasons, recording his masterpiece Heroes there along with many other influential tracks, and producing a Berlin run that many cite as his finest three recordings.

Depeche Mode’s hat-trick was just as dramatic – at least as far as the band were concerned – as it would give them their future career and sonic identity.

Construction Time Again, Some Great Reward and Black Celebration – the band’s third, fourth and fifth albums – represented an absolute about-face for the Mode sound. In just four years that sound transformed from that found in dizzying teen electronic love songs like The Meaning of Love…

… to the stifling, hypnotic and 'death is everywhere' feel of Fly On the Windscreen.

The band grew up from clean-cut synth kids, through stroppy students of industrial gloom, to young men of electronic post rock. And while this particular Berlin Trilogy will not resonate historically as much as Bowie’s, it did take them to a place – and give them a following – that would see them still hoovering up huge live audiences some 40 years later. Time to find out how they did it…

Construction Time Again

While Gore had started taking the Mode sound away from Vince Clarke’s pure pop on second album A Broken Frame, it would be third album Construction Time Again where their focus narrowed towards a new sound and era.

Alan Wilder had replaced Clarke by now and could write a tune or two, Gareth Jones was drafted in to help record the album, and a certain piece of technology would help nudge their sound along.

“Samplers had really just come out,” Gore said in the fantastic BBC documentary, Synth Britannia. “It was a whole revelation to us. We were just going out smashing pieces of metal with sledgehammers.”

We just sampled everything and played melodies and beats over it

Gareth Jones

Gareth encouraged this kind of experimentation with samplers including the Synclavier, and the initial bashings took place in derelict parts of East London, with plenty of waste products to hammer and plenty to record.

“We just sampled everything and played melodies and beats over it,” Jones said. “We did it as much as we could and a lot of fun it was too. I had a portable Stellavox recorder, a high-quality 1/4-inch reel-to-reel machine with mics, and we went out into the industrial wastelands of Shoreditch and sampled stuff and put it into a Synclavier for the record.”

"We felt that a lot of what we were doing was defining new sonic territories,” he told Sound On Sound in 2007 of how the sampling process affected the band’s sound. “They wanted to experiment and they wanted to grow, and they were fed up with their synth-pop image. That was part of the gradual darkening of the Depeche Mode sound.”

Indeed it was. While some songs on the album sound like they were almost created to match the samples – Pipeline (above) being the most obvious – others saw the band take on big subjects.

Construction Time Again really started to see us form the basis of what we are today

Andrew Fletcher on Synth Brittannia

Gore’s songwriting would go onto tackle sex and religion on future Depeche albums, but here he was more interested in greed, while newcomer Wilder matched the girth of the subject matter with Two Minute Warning and the Landscape is Changing.

Closing track And Then would set a future template for the band’s albums to finish on a high, but the highest track would be – and still is – Everything Counts. This brought everything the album strove for together – a new direction, new lyrics, new subjects and new samples – and ladled on some memorable melodies that Clarke would have been proud of. It was the bridge between the old and new and is still the highlight of any DM gig today.

“Construction Time Again really started to see us form the basis of what we are today,” Fletch told Synth Britannia, and he was spot on the money with that.

Some Great Reward

The sampling antics continued well into the next Depeche Mode album, 1984's Some Great Reward. While interviewed in Electronic Sound Maker in the same year, Alan Wilder noted: “For us, the Synclavier is the first synthesizer/sampler you can honestly called 'limitless'. Without exaggeration, you are limited, quite literally, only by your imagination.

The Synclavier is the first synthesizer/sampler you can honestly called 'limitless'. Without exaggeration, you are limited, quite literally, only by your imagination.

Alan Wilder

"We are spoiled in that we remember what it was like being limited to using a Roland Jupiter, but, as we are a band which is committed to opening new vistas of sound, analogues have become rather pale next to the digitals, and especially, of course, the Synclavier.”

And there was a slight shift in what the band were sampling, although it was still pretty industrial. “On one of the tracks on the album, Blasphemous Rumours,” the band's Alan Wilder told International Musician in 1984, “we sampled some concrete being hit for what turned out to be the snare sound. All that entailed was us hitting a big lump of concrete with a sampling hammer.”

While we search for this so-called ‘sampling hammer’, here's said Blasphemous Rumours.

In the same feature, Wilder gave a detailed breakdown of how samples were used in album highlight and hit single People Are People.

“The bass drum at the beginning was just an acoustic bass drum sampled into a Synclavier, then we added a piece of metal to that – just a sampled anvil-type sound – to give it a slight click and make it sound a bit different.

"The main synth sound is the actual ‘synth’ sound on the Synclavier, that’s the one that plays the bass riff. But the bass sound is a combination sound too, with part of it being an acoustic guitar plucked with a coin, which sounds very interesting when the two sounds are sequenced together.”

Check out how that all came together here…

Gore also revealed his perfect method for capturing his samples in the first place, and it might surprise you.

“Walkmans are good for sampling too, because they get a very impure sound that can often be really interesting. But if we want a very pure sound then we’ll take the thing, say a bit of scaffolding, into the studio and mike it up in the proper conditions and get a clean sound.”

All that entailed was us hitting a big lump of concrete with a sampling hammer.

Alan Wilder

The band would sample toys or anything odd they could get their hands on and use Synclavier, Emulator and PPG machines to manipulate them. Gore admitted in 1986: “Sometimes we use old favourites — like one sample which we first used on People Are People. It's a Hank Marvin-type guitar sound, an acoustic guitar plucked with a 50-pfennig piece.”

Good to see the band employing the then-local currency to good effect, and here’s a home video of the recording sessions.

But while the sessions here look happy, the band had started to spend more time in Hansa Studios doing less and less.

Martin told Uncut in 2016: "In Berlin, I remember Some Great Reward being a bit of struggle. Maybe because we’d had a bit of success we could spend a bit more time. It was a nightmare – we spent nine days to mix one track. You’re really going up your own arsehole if you spend nine days mixing something."

You’re really going up your own arsehole if you spend nine days mixing something

Martin Gore

Yet mix they eventually did, and the results maintained the upward trajectory and industrial sound the band was now enjoying. Some Great Reward is dominated by the clanging of People Are People – another Mode track with lyrics more relevant than ever – and the panting of Master & Servant.

Yet there are gems to be discovered in between. Wilder’s If You Want broods and builds to a crashing pop song, with one of Gahan’s best vocals, while arguably the finest track, Blasphemous Rumours, is one of Gore’s earliest but probably greatest snarling swipes at religion.

Then there’s Somebody…

This is the track that had many people talking because there were (blasphemous) rumours that Martin had recorded it naked. Shock! Innocent times indeed, and you have to remember that the internet was a few years away at this point.

Speaking to the Melody Maker in 1984, Martin admitted his studio cheek: "Somebody just needed three takes, mainly to get the sound okay – and really uses the bare essentials. In fact, I sang it completely naked in the cellar of the studio which we use for ambience."

I sang it completely naked in the cellar of the studio which we use for ambience

Martin Gore

Wilder recalled it happening in a different part of the studio in the DVD documentary for the 2006 rerelease of Some Great Reward.

"It was probably the first of what you'd call an acoustic performed track on an album. In fact, Martin sang it naked. It was his call [laughs].

"I turned the piano away as I was playing, but yeah, we recorded it live, just him and me, in the big studio 2 hall, and he stripped off for that one."

Black Celebration

As digital technology swept in during the 80s so Depeche Mode embraced it for their fifth album – and some might say best of this particular Berlin Trilogy – 1986’s Black Celebration.

Believe it or not, a computer was also present – a BBC Micro by all accounts, used for some sequencing – as was the old faithful ARP 2600 analogue synth (used on just about every DM album).

However, Black Celebration probably represented a peak in sampling for Depeche Mode, with both the Synclavier and Emulator used at full power.

“Usually we spend two or three days before recording just sampling sounds,” Gore said in 1986 in an Electronics and Music Maker interview. “Then we sample as we go. If somebody has a good idea, we just stop recording and do some sampling.

"There's a Black & Decker drill in the opening of Fly on the Windscreen, and the rhythm of Stripped was made up of the sound of an idling motorbike played half-an-octave down from its original pitch.”

There's a Black & Decker drill in the opening of Fly on the Windscreen

Martin Gore

In fact, the idling motorbike sound is an Emulator preset as Wilder said in the Hanging On Your Words Depeche Mode biography.

"The entire backbone of Stripped was based around an idling motorbike sound generated from the original Emulator - preset 1, and a bass drone that was eventually fed through a Leslie cabinet. Additional sounds such as the ignition of Dave's Porsche 911 and an array of fireworks were recorded by Gareth in the studio car park."

It might be a preset, then, but on Stripped, it is possibly the greatest use of a preset ever. Here's one of Depeche Mode's best five tunes.

Further sampling would dominate the Black Celebration recording sessions and, unusually, the album even featured an additional vocalist in the form of Daniel Miller. Well, not that you'd really know it. Alan Wilder said on his Recoil website: “Dan Miller says ‘Horse’ repeatedly very fast on Fly On The Windscreen and 'Over and done with'."

Surprisingly, given the amount of digital technology involved, Black Celebration doesn't sound like the sterile recording that much of that technology led to during the latter part of the 1980s. In fact it's anything but.

The album starts as strongly as any Depeche album before or since skipping between the subjects of lust and death with gay abandon, all while enjoying the blackest of celebrations.

But while the themes are certainly dark, some of Martin's best songs give the Mode's fifth outing more soul than any previous offering. Tracks like Dressed in Black, Sometimes and Here is The House offer surprisingly tender moments between the bangers of Stripped and the stalking A Question Of Time. There's even time to diversify the rage aimed outwards with a brilliant swipe at the tabloid media in the much underrated New Dress.

The Legacy

Black Celebration is the last in the Mode's own Berlin Trilogy but, in a sense, is the first true, fully-formed and rounded Depeche Mode album. It reaches the darkest depths and sonic heights that they were aiming for – consciously or not – and takes them well and truly away from the synth-pop and into a world that they would continue to explore for decades after.

It's something of a fitting bookend, then, to the working relationship the band had with Daniel Miller and Gareth Jones. While a peak in the band's catalogue – we'd put BC in our top three Mode albums – Miller realised that its recording would be the last to feature all six of them in the studio.

Towards the end we were getting too much into a routine of working together and it was definitely time for a change

Daniel Miller

"Towards the end of Black Celebration," he told Classic Pop, "I think we all needed a break. I think it was mutual. They wanted a different pilot and it wasn’t the best experience towards the end. It was kind of frustrating for everyone and I wanted to focus on the label so it came just at the right time.

"It was me and the band and Gareth Jones for three albums: Construction Time Again, Some Great Reward and Black Celebration. We had good fun, it was nice, we had a really creative time and it was really enjoyable. I remember those days fondly but also towards the end we were getting too much into a routine of working together and it was definitely time for a change.”

It was, of course, a fantastic decision as the band's greatest albums would follow, but if it wasn't for this trio of Berlin recordings, there would have been no Songs of Faith and Devotion, no Violator and no world domination.

Jones, Miller, Hansa and Berlin had their influence on a band that is still selling out 90,000 capacity stadiums on two-year long world tours, and these three albums should always be seen as the markers in the sand that enabled them to get there.