GOLDEN, Colorado - Breathe easy: There's good news from Mars.

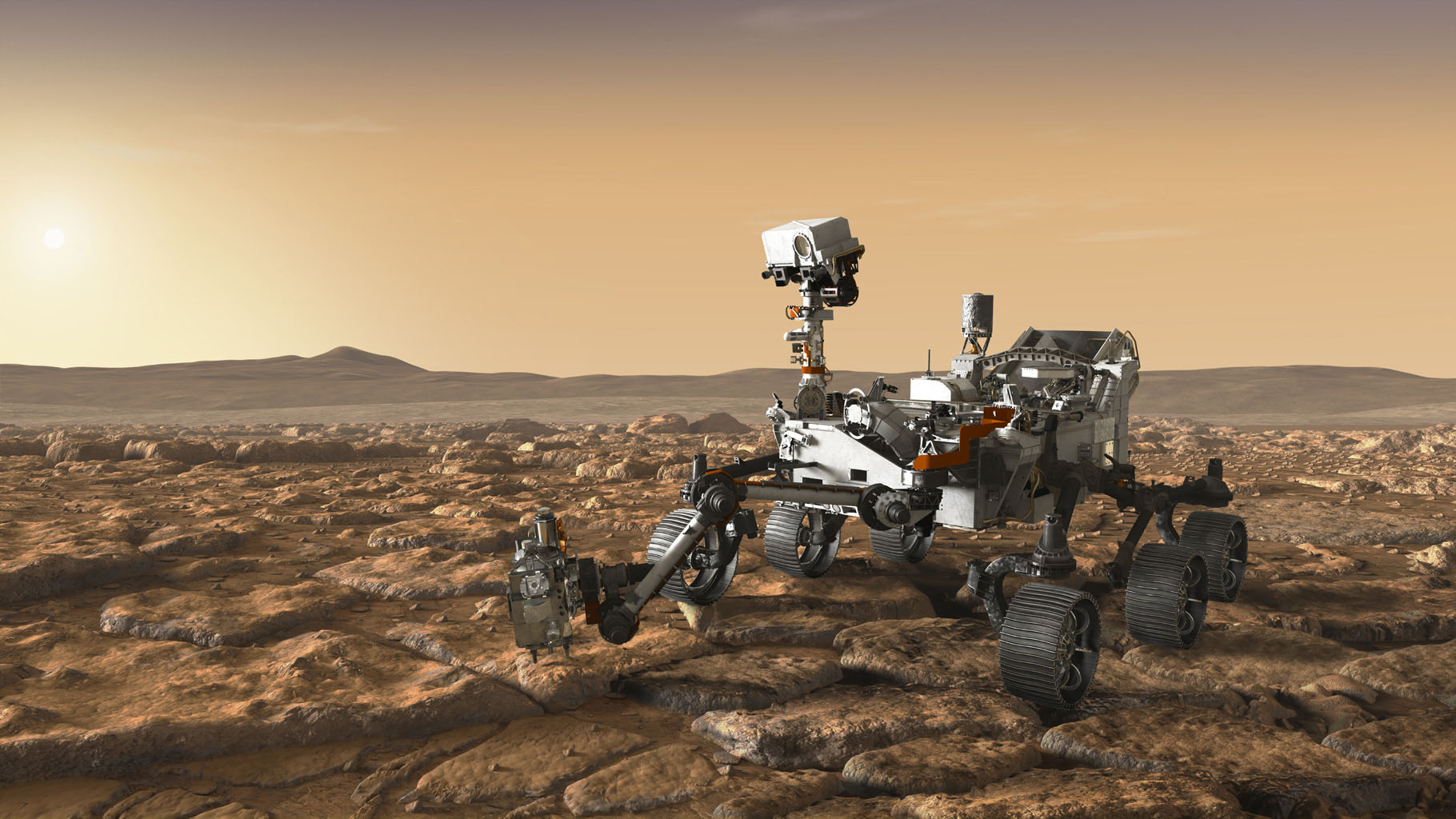

Tucked inside NASA's Perseverance Mars rover is a device known as MOXIE, short for Mars Oxygen In Situ Resource Utilization Experiment. MOXIE is the first experiment to suck in the planet's thin, carbon dioxide-laden air and transform that native resource into oxygen. The toaster-sized device, if built to a larger scale, can be used not just for astronaut expeditions to Mars for breathing, but also for rocket fuel.

Earlier this month, the experiment achieved a major milestone when researchers pushed MOXIE to a maximum production level — a factor of two higher than reached earlier.

Related: Perseverance rover: NASA's Mars car to seek signs of ancient life

Riskiest run

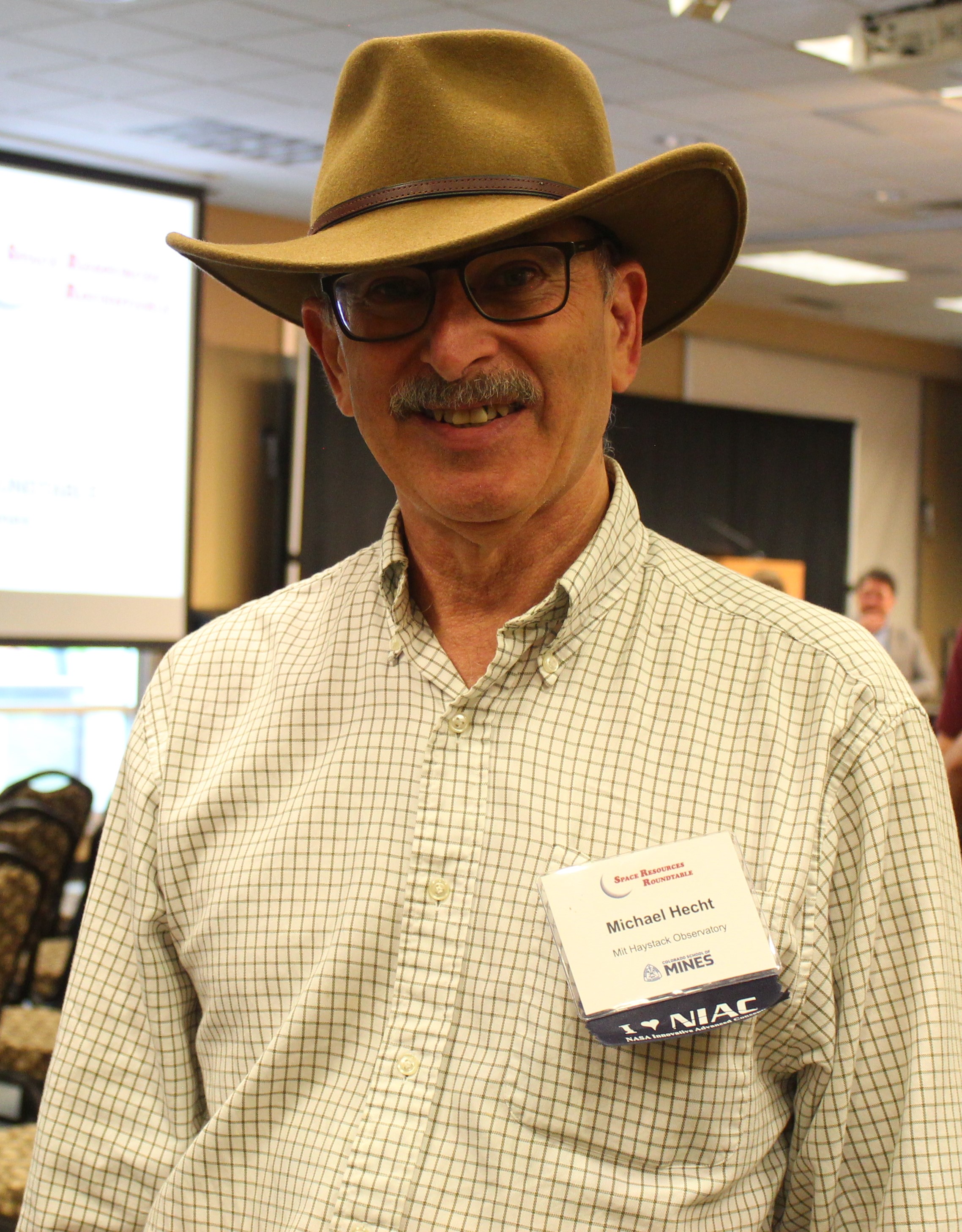

"We got great results," said Michael Hecht, MOXIE's principal investigator and an associate director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) Haystack Observatory in Westford, Massachusetts.

"This was the riskiest run we've done," Hecht told Space.com in an exclusive interview. "This could have gone wrong," he said, and could have led to minor damage to the instrument, but it didn't. The milestone setting Mars run took place on June 6, operating during the Martian night, and lasted 58 minutes, Hecht said.

The requirements for MOXIE were to produce 6 grams of oxygen an hour, a rate that was eventually doubled. "We rolled the dice a little bit. It was 'hold your breath and see what happens,'" Hecht said.

Informally dubbed by Hecht and his team as "the last hurrah," MOXIE delivered the goods on its 15th run on Mars since first gulping up Martian atmosphere within Jezero Crater on April 20, 2021.

The challenge all along, Hecht added, has been to define ways to operate on Mars more efficiently by cranking out a higher yield of oxygen.

Voltage vigilance

Hecht presented a review of MOXIE, detailing a Martian year of on-the-spot resource utilization on the Red Planet at the 23rd meeting of the Space Resources Roundtable, held June 6-9 at the Colorado School of Mines.

MOXIE weighs roughly 40 pounds (18 kg) and is designed to pull in Martian air using a pump before using an electrochemical process to separate one oxygen atom from each molecule of carbon dioxide. As a byproduct, carbon monoxide is produced, as is a black residue of solid carbon that can gum up the works inside the device, Hecht said. So voltage vigilance is required as MOXIE performs its high-temperature, oxygen-making work, he added.

Operating one hour at a time, MOXIE ran seven times in calendar year 2021, mostly to prove that the instrument can operate in the different conditions the planet experiences throughout the Martian year. (A year on Mars lasts twice as long as it does on Earth due to the Red Planet's full-circle swing around the sun.)

In 2022, MOXIE technologists focused more on pushing the unit's capabilities, as well as developing new operating modes. All in all, the earlier start-stop set of 14 runs added up to 1,000 minutes of operating time. "It's been an exciting ride," Hecht told the Colorado School of Mines audience.

But MOXIE is a technology demonstration, and like many other demonstrators, its long-term life is tied to funding. Research money for MOXIE is set to end at year's end, Hecht said, with the MIT lab that carries out the work on the lookout for new collaborations.

Full-scale system

As for what's next for MOXIE, Hecht said the experiment results encourage the development of a full-scale system here on Earth, one that pumps out oxygen continuously in auto-mode and is able to generate 25 to 30 tons of oxygen to support a human mission on Mars. "It's all about lifetime. We run an hour at a time. To do this in the future we will have to run for 10,000 hours."

Understanding just how far MOXIE can be pushed before it degrades is important. "On Mars you don't get a second chance," Hecht told Space.com. "We could turn it on at 12 grams an hour and let it rip for a long time."

Perhaps there is value in coming back in a year, Hecht observed, to turn the experiment on again to see if anything has degraded just from aging and exposure to the Martian environment.

"MOXIE isn't going anywhere being nice and safe on Mars," Hecht said.