Most of us know what a heatwave feels like on land – sweltering heat for days. But oceans get heatwaves too. When water temperature goes over a seasonal threshold for five days or more, that’s a marine heatwave. They do their worst damage in summer, when the ocean is already at its warmest, but they can occur any time of year.

Over 90% of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases has gone into our oceans. So it’s no surprise marine heatwaves are getting much more intense and more frequent. This year has been off the charts. From April this year, the world’s average ocean temperature has been the highest ever recorded.

Since the 1980s, satellites have revolutionised ocean science by making it possible to take daily measurements of ocean temperatures. But satellites watch from above. They can’t see what’s happening below the surface.

Our new research explores what’s happening in deeper waters. It turns out, marine heatwaves aren’t just on the surface. In the most devastating marine heatwaves, heat can penetrate right down to the sea bed. Remarkably, some heatwaves only affect the seafloor.

Why do deep marine heatwaves matter?

While we usually only see sea creatures at the surface of the ocean, there’s life all the way down. In the shallower seafloors of the continental shelf – the sunken parts of our continents – live fish, kelp beds, sponges, cold water corals, shellfish and crustaceans.

These shallow oceans are, on average, less than 100 metres deep. When the shelf ends, there’s usually an abrupt slope into the deep ocean, where there are kilometres of water between surface and seabed.

Marine heatwaves are damaging to life in the seas covering the continental shelf. Creatures here are sensitive to extreme temperatures, just like those at the surface. But “extreme” to them is different to what we think of as extreme. If you’re used to water at 12℃, a heatwave of 15℃ can be devastating.

When marine heatwaves strike, they can kill. More than a billion sea creatures died during a single heatwave off the coast of the western United States and Canada in 2021. This year, extreme heatwaves have hit large parts of the oceans during the northern summer.

Fish and other creatures that can move do so, heading towards the poles or down deeper in search of cooler water. Those that can’t have to endure it or die. Heatwaves can trigger migration. New species arrive, seeking refuge and can alter the ecosystem.

Read more: An 'extreme' heatwave has hit the seas around the UK and Ireland – here's what's going on

We don’t know much about deeper marine heatwaves

The seas covering the continental shelf are relatively shallow compared to the kilometres of water in the deep oceans. But even so, it’s impossible to see what’s going on below using satellites or high-frequency radar.

The sea is a hostile environment. Instruments are subject to high pressure, corrosive salt water and marine organisms like oysters and sponges settling on them. This is one reason why we only have very limited data on long-term trends in temperatures under the surface. But these records are vital to calculate typical temperatures for the time of year and to figure out what constitutes an extreme.

Australia is one of the few places generating this kind of valuable data long-term. Off the coast of the southeast lie many oceanographic moorings – a floating collection of sensors anchored to the bottom. One of these has been measuring daily temperatures from the surface to the seafloor 65 metres down since 1993.

Our earlier research found marine heatwaves at depth can actually be more intense and last longer compared to the surface. But why?

In our new research, we looked at the temperature data closely. We found marine heatwaves come in a variety of types and have different causes. We also found some types of marine heatwave are more likely during particular seasons.

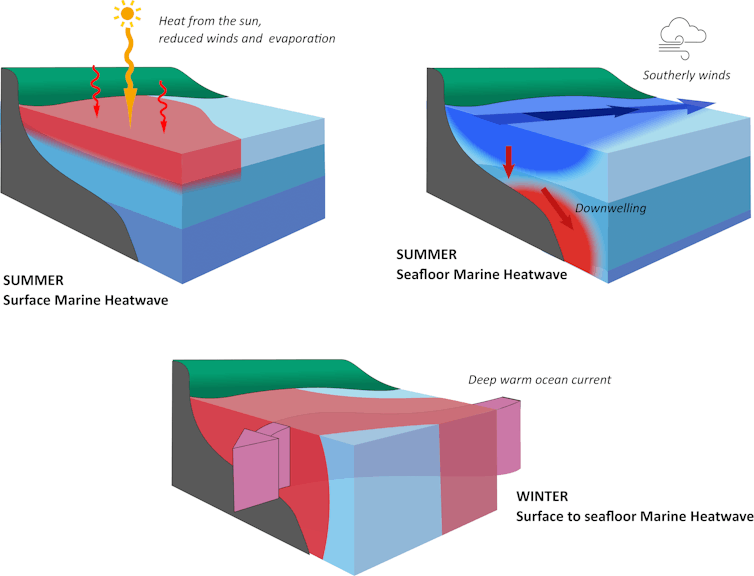

For instance, winter marine heatwaves often run from surface to seafloor. They occur when the powerful, deep and warm East Australian Current snakes westward towards the coast. As the current swings over the continental slope, it drags warm water over the shelf and close to the coast.

In summer, Australia gets two very different types of heatwave in our oceans. The first occur when we get blue-sky weather. With few clouds, more heat from the sun gets into the oceans. They can also occur when there are weaker winds and less ocean cooling from evaporation. These heatwaves are confined to the surface and a few metres below.

Then there’s the second, a very weird heatwave system that only appears close to the seafloor. These are produced when strong wind creates currents driving warm, shallower water down to the bottom. On the east coast, these currents come from cold winds from the south. So even while you’re shivering through cold winds from the Southern Ocean, the ocean seafloor may be sweltering through a heatwave. These may be the most destructive to ecosystems but go all but unnoticed.

Marine heatwaves are not created equally

Our research has shown marine heatwaves come in different flavours. That matters, because it will allow us to get better at predicting if a heatwave is about to strike our oceans. And it will let us anticipate which parts of the water column are about to be hit, and which ecosystems.

Of course, slowing ocean warming and preventing marine heatwaves from damaging ecosystems means slashing carbon emissions. But while we work on that, this knowledge could give us time to find strategies to reduce the undersea death toll – and the damage to tourism and fishing which rely on these ecosystems surviving.

Read more: Coral reefs: How climate change threatens the hidden diversity of marine ecosystems

Amandine Schaeffer receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Alex Sen Gupta receives funding from the Australian Research Council

Moninya Roughan receives funding from the Australian Research Council, and Australia’s Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) – IMOS is enabled by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.