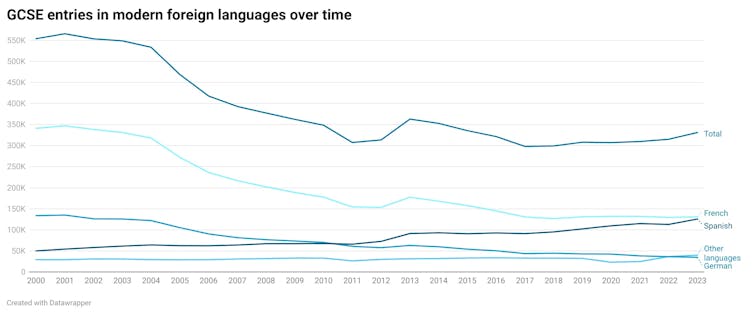

Figures for GCSEs taken in 2023 show that entries for GCSEs in languages have increased slightly from last year. Despite this, the number of pupils taking a modern foreign language stands at less than 60% of those that did in the peak year of 2001.

The decline in the number of pupils taking modern foreign languages at GCSE dates back to the government’s decision to make the subject optional from 2004. At this point, the number of students taking an exam in the subject declined sharply and have never recovered.

There was a short-lived “EBacc effect” around 2012-13 after the government introduced the English baccalaureate. To achieve the EBacc, students have to take a number of required subjects at GCSE, including a modern foreign language. This led to schools encouraging students to take the subject.

Some schools continue to make modern foreign languages compulsory. But often, where students have a choice, they are not picking the subject. But the study of a language has clear benefits, both to individual students and to society as a whole.

Avoiding languages

Despite the great work of teachers, there are some clear reasons why modern languages are unpopular among students. Historically, languages have been graded more harshly than other subjects. The curriculum focuses on a comparatively narrow range of topics and does not take good account of the cultural aspects of language learning. It will be updated from 2024, though it remains to be seen how meaningful these changes will be.

The global dominance of English, as well as the perception that learning a language is only useful if you will need it for work, also puts students off.

But students are interested in language learning – just not so much in taking a GCSE in a language. Students have told me that they would like to learn the languages spoken by their friends, or of countries that they visit, or where they admire the culture. They consider multilingualism to be of value.

I research self-determination theory, which holds that there is a continuum of different forms of motivation. Self-determination theory suggests that if we feel that we are doing something because it is aligned with our own values and beliefs, then we are likely to be more engaged, to achieve better outcomes and, crucially, to continue undertaking that activity. We’re also more likely to thrive – self-determination theory tells us that motivation and wellbeing are linked.

By contrast, if we feel we are only doing something to meet the expectations of others – such as taking a compulsory GCSE – we are less likely to engage, to succeed and to continue.

The importance of choice

My work in schools has shown that having a choice clearly affects students’ motivation. Those who had a choice were more motivated to learn than those who did not, probably because the students who chose the subject are those who valued it personally.

This means that making languages compulsory again is probably not the answer. Those who have to take the subject as part of an EBacc pathway may feel they have to engage with it because it is what is expected of them.

Instead, the way the subject is perceived by students needs to change. Where it is seen as being of personal value, students are likely to take the subject for their own reasons, with all the associated benefits that come with that. Where the value is seen as general (it’s “good” to speak another language) or is not really recognised at all, then even if students take the subject their motivation will be affected.

The issues around grading are also likely to affect motivation. If a student considers that they are unlikely to be successful in language learning (which, in school terms, means getting a good grade, regardless of what it might mean to be a successful language learner in other contexts), motivation to engage in it in the first place is likely to be low.

Addressing the low levels of take up of modern foreign languages at GCSE level is not an easy task. The slight recent rises suggest that students are interested, but it will take more than revising the exam specifications to have real impact. It would help if exam boards and the government considered why students are motivated to learn a language in the first place.

Abigail Parrish does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.