The Supreme Court decision reversing Roe v. Wade’s protection for abortion rights was a predictably partisan ruling. All of the justices appointed by Republican presidents voted to uphold the Mississippi law restricting abortion, while all three appointed by Democratic presidents dissented.

In keeping with this partisan trend, the states that are currently restricting abortion are in the Republican strongholds of the South, Midwest, Great Plains and Mountain West. Those that are protecting abortion access are Democratic and are heavily concentrated in the Northeast and the West Coast.

But that was not the case at the time of the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling in 1973. Both before and immediately after the Roe v. Wade decision, many prominent Republicans, such as first lady Betty Ford and New York Gov. and later Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, supported abortion rights. At the same time, some liberal Democrats spoke out against abortion rights, including Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, vice presidential candidate Sargent Shriver and his wife Eunice Kennedy Shriver, as well as civil rights activist Jesse Jackson.

The anti-abortion movement was strongest in the heavily Catholic, reliably Democratic states of the Northeast, and its supporters believed that their campaign for the rights of the unborn accorded well with the liberal principles of the Democratic Party.

When I researched the early history of the anti-abortion movement for my book “Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement before Roe v. Wade,” one surprising finding was that the pre-Roe anti-abortion movement was filled with liberal Democrats who had supported the federal anti-poverty initiatives associated with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s and President Lyndon Johnson’s social programs in the 1960s. They wanted to couple abortion restrictions with additional efforts to fight poverty and expand government-funded health care.

Catholic and Democrat

Most of the pre-Roe anti-abortion activists in the United States were inspired by 20th-century Catholic social teaching that connected the right to life for the unborn with a larger ethic of concern for the less fortunate. Like the majority of Catholic voters at the time, many were Democrats, and they hoped that a party that championed the poor would likewise be interested in protecting fetal life.

Many of them, in keeping with the teachings of their church, held conservative views on issues of sex and reproduction. They also, in keeping with Catholic social teaching, believed that the state had a responsibility to care for the poorest of its citizens and therefore supported liberal Democratic economic initiatives.

Many of these abortion opponents, including the liberal Republican Sen. Mark Hatfield, an evangelical Baptist, and the Lutheran minister Richard John Neuhaus, who later converted to Catholicism, opposed the Vietnam War, which they believed was a violation of the right to life, just as abortion was.

They did not want to condemn women who resorted to abortion, but instead hoped to offer them social assistance that would help them avoid that choice. “It’s not so much that the woman rejects the child as that society rejects the pregnant woman,” Edythe Thompson, a member of the student organization Save Our Unwanted Life, which characterized itself as “an extremely liberal group,” declared in 1971.

Shift to the political right

After Roe, the anti-abortion movement’s defense of fetal rights came into conflict with the feminist movement’s insistence that abortion rights were nonnegotiable women’s rights. Abortion opponents often argued that abortion harmed women emotionally and physically and gave an excuse to men to abandon their responsibilities as fathers. As the anti-abortion self-described feminist Juli Loesch phrased it in the 1980s, legalized abortion meant that “a man can use a woman, vacuum her out and she’s ready to be used again.”

But the women’s rights movement did not accept this argument, and after the mid-1970s, an increasing number of liberal Democrats did not either. The Democratic Party endorsed abortion rights in its 1976 platform and strengthened this endorsement in the 1980s.

Although anti-abortion activists began their movement with a strong belief in an expanded social welfare state, their search for allies in their quest to protect fetal life through public law led them into an alliance with conservative Republicans who did not support an expanded social safety net.

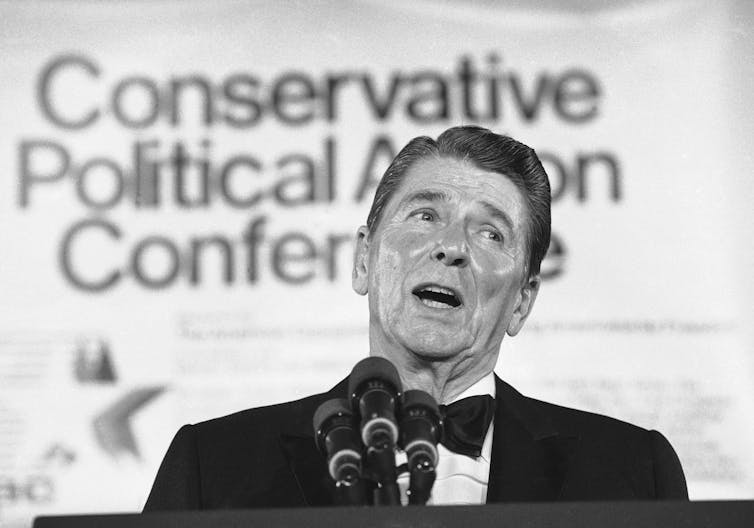

Ronald Reagan’s support for a proposed anti-abortion constitutional amendment that would have banned abortion nationwide won plaudits from anti-abortion activists across the political spectrum.

Although Cardinal Joseph Bernardin – the archbishop of Chicago – and other political liberals in the anti-abortion movement criticized the Reagan administration’s nuclear arms buildup, politically conservative opponents of abortion generally did not. The nation’s largest anti-abortion organization, the National Right to Life Committee, used its political action committee to raise money for any candidates who would vote to restrict abortion and said nothing about the Reagan administration’s stance on nuclear arms, because its leaders believed that the fastest route to reverse Roe v. Wade was to work with all politicians who opposed abortion rights. In practice, this meant that most of the candidates the organization supported were Republicans, especially after the early 1990s.

With only a few exceptions, anti-abortion activists largely abandoned the goal of expanding maternal and prenatal health care or treated this as a distant secondary priority to their main task of legally restricting abortion.

As late as 1995, the National Right to Life Committee expressed concern that a conservative welfare reform that both President Bill Clinton and the Republican Congress supported would increase the abortion rate by restricting social assistance to low-income unmarried women who had additional children. By the 21st century, however, concerns about social welfare cuts were no longer on its agenda as it became increasingly focused on shifting the Supreme Court to the right to overturn Roe v. Wade.

The movement of large numbers of Southern white evangelicals into the anti-abortion movement also encouraged this conservative turn. Unlike many Northern Catholics, Southern white evangelicals had a deep antipathy to the social welfare state, and when they became anti-abortion activists in the 1980s, their political efforts focused almost entirely on abortion restrictions, not anti-poverty initiatives.

The anti-abortion movement’s politics today

By the time the Supreme Court reversed Roe, the anti-abortion movement had become so thoroughly allied with conservative Republican politics that it was difficult to imagine a time when liberal Democrats who supported an expanded welfare state were leaders in the movement.

But some abortion opponents are already realizing the limits of a strategy that is narrowly focused on fighting abortion only through legal restrictions. They are calling for renewed efforts to secure family leave policies and economic assistance for low-income pregnant women.

If some abortion opponents focus on this goal now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, it will not be a new approach for the movement. Rather, it will be a revival of the original ethos that the founders of the movement proposed more than half a century ago, before Roe v. Wade was even issued.

Daniel K. Williams received a research fellowship from the James Madison Program at Princeton University in 2011-12.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.