If you’ve ever been trapped in a conversation about “dream dinner party guests”, you’ll know the curious schadenfreude of watching people work out which aspects of their personality they want to showcase. The last time it happened to me, someone picked Jason Momoa and Channing Tatum for “eye candy”, alongside – who else? – Martin Luther King Jr. While we’ll perhaps never know Aquaman’s views on the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, the conversation did highlight our society’s continued deference to jacked, hyper-masculine bodies.

Tatum himself was in the news earlier this year for speaking up about his own physique, specifically in the Magic Mike films. Appearing on The Kelly Clarkson Show, the actor deflected praise for a topless picture from that era, explaining that the routine was “unhealthy” and that it had required starvation to achieve his look. Last week, social media was once again obsessing over Zac Efron’s body as an image leaked of him filming a new role in a wrestling movie. This is a man, you may recall, who has been open about his struggles with body image, diet, and taking so many diuretics to get into shape for Baywatch (2017) that he fell into “a pretty bad depression” and suffered from insomnia. If the tide is finally beginning to turn in how we talk about the societal expectations put on men’s bodies, it’s long overdue.

Historically, of course, the stereotypical image associated with eating disorders and body dysmorphia has been of a painfully thin young woman – and with good reason. Women’s bodies have been scrutinised, criticised and idealised by men for millennia, a power dynamic that has accelerated over the last century with the rise of TV and film, supermodels, Instagram – developments that ushered in a cavalcade of highly edited and stylised images, framed by and for the male gaze. It is only to be expected, then, that data and studies around the subject have typically focused on women.

In 2022, it’s harder to make that case. A study last year found that the majority of men (54 per cent) displayed signs of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), compared to 49 per cent of women. If those numbers seem startling, based on the visibility of body image case studies and campaigns both online and offline today, one of the main factors will come as no surprise: too many men are simply not talking about it. Worse still, in some cases they aren’t even recognising that their obsessive thoughts about their own weight and body image may have spiralled into dysmorphia.

Sam Thomas, who started a charity in his mid-twenties called Men Get Eating Disorders Too and has written extensively on mental health and addiction, experienced both body-image anxiety and an eating disorder – but not in the order you might imagine. Despite developing bulimia at the age of 13, a result of what he describes as a “trauma response” to homophobic bullying, Thomas says he had “no real concerns at all” about his weight or size back then. It was only years later, as he was recovering in his early twenties, that concerns about how he looked took hold.

“A lot of people assume that eating disorders are all to do with body image, but that wasn’t the case with me,” he explains. “It wasn’t really until I left Liverpool to move to Brighton when I was 18 and started making friends for the first time, in the LGBT scene, that I started to realise how bothered everyone was about how they looked.”

After developing into an incredibly thin marathon runner, Thomas started hitting the gym and became “very muscular and defined very quickly”. He found he could eat whatever he wanted and burn it off later in a workout, which proved appealing. But while going to the gym is a positive part of his life now, back then it was a totally different story. “I just kept swinging from one unhealthy coping mechanism to another,” he says.

One of the key reasons why body image issues in men may frequently go unchecked is connected to the type of male body shapes that are fetishised. The extreme thinness often associated with anorexia and bulimia will more readily draw concerned enquiries, while someone whose obsession with the gym is fuelling their mental health crisis is more likely to be commended for their commitment, just like their Hollywood idols.

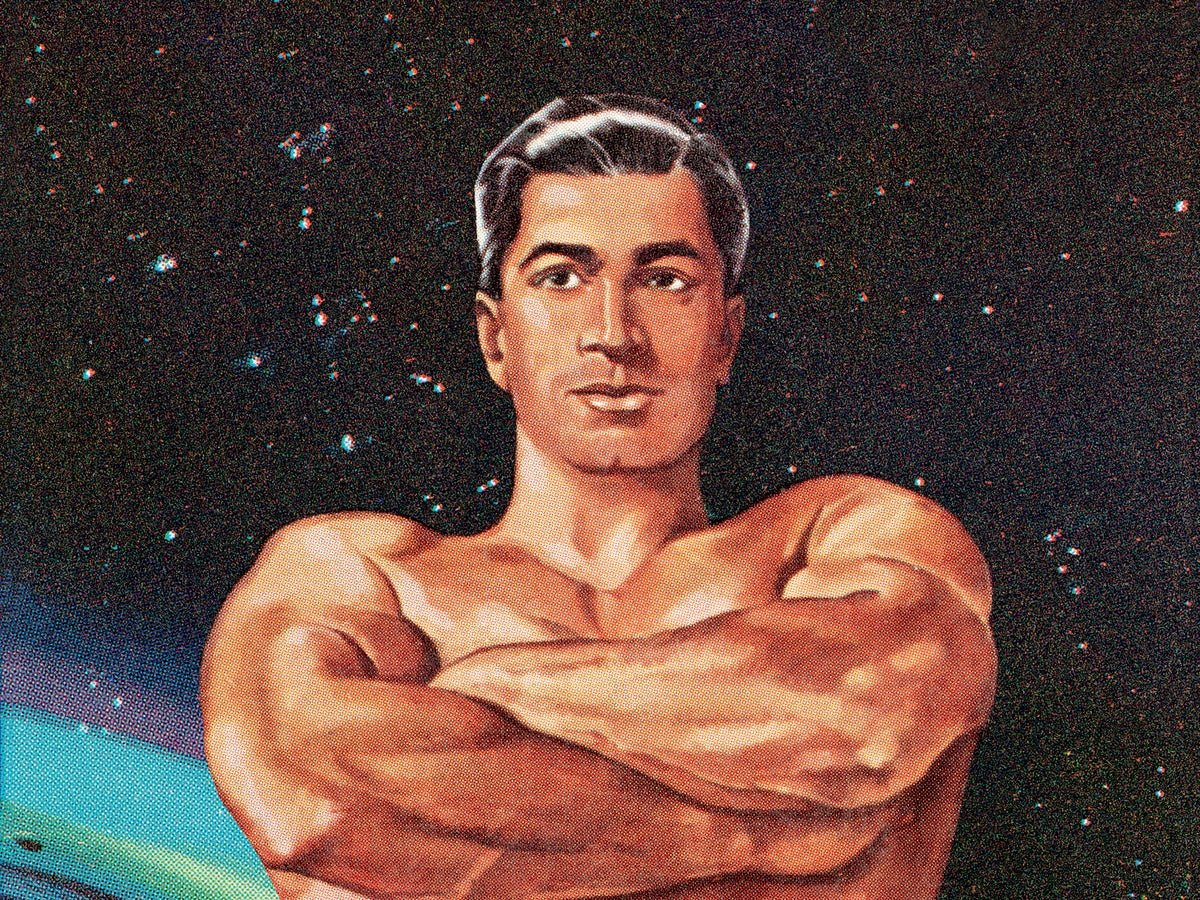

“There’s no one body image ideal for men, whereas historically there was really one ideal for women – the thinner the better,” says Thomas, acknowledging that things have become “a bit more complex now because of trends in plastic surgery and Instagram”. While men often feel pressured to lose weight to reduce their gut and look good in skinny jeans, a simultaneous pressure is exerted to gain weight in order to acquire massive, vein-popping biceps. As both Tatum and Efron have been at pains to point out, that image is a biology-defying aesthetic straight out of a comic book, and no more realistic than a woman with a 16-inch waist and a J-cup bust.

“With men, there’s been this very ‘alpha male’ look with big muscles, but on the other hand you’ve got this slender-but-defined look, and not much going on in between. I used to say it’s like trying to walk right and left at the same time,” he adds. “I think a lot of men did not know what to aspire to.”

Of course, part of the problem with BDD is that how bodies are perceived by others can sometimes be irrelevant: if someone has convinced themselves they are the ‘wrong’ shape, the area of the body that needs the toughest workout is often the brain. Erene Hadjiioannou, spokesperson for the UK Council for Psychotherapy, says that finding out what dysmorphia means to the individual is essential.

“In psychotherapy you’re working with someone’s subjectivity, so if someone uses the term ‘body dysmorphia’ my first thought would be to unpack what that actually means to them,” she says. “Where does that come from? What’s perpetuating it? Because really what you’re working with is internalisations of negative messages or what’s socially acceptable, and how people carry that around and embody it.”

Gender variances don’t just show up between cis men and cis women, either. For both trans men and trans women, the pressure to conform to a hyper-gendered body image can be exacerbated by the expectation to “pass” as male or female in public; conversely, non-binary or genderqueer folk often speak about societal expectations of androgyny – that an appearance deemed too heavily masc- or femme-presenting might raise questions about the validity of their identity. It seems there’s no escaping the feeling that our bodies might not be “performing” in the way society would like them to.

While the temptation may be strong to simply tell people to “be themselves” or “be proud of who you are” – hashtag blessed! – it’s worth remembering that there are considerable social rewards for people who ignore that advice and instead work to emulate everyone else’s idea of physical perfection. If that sounds like the bleakest capitalist model of dehumanisation imaginable – reducing people to an assemblage of botox and lip-fillers that improve your chances of attaining mental wellbeing and intimacy – well, that’s pretty much where we are.

“I would describe it more in the ways our bodies are being used as currency, in a transactional sense, particularly in the early stages of a relationship,” Hadjiioannou says. “It really takes away from the idea of ourselves as a whole person, if the focus is purely on what your profile picture looks like.”

What, if anything, can we do to try and fight something that seems so powerful and all-pervasive? The likes of Tatum and Efron speaking up about how utterly miserable and unhealthy their lives became in order to get “shredded” for certain roles can only help, for sure. Thomas says he wants to see a more diverse range of male bodies represented, too. “For women, there’s increasingly a lot of representation for ‘plus-size’ figures, but there isn’t really an equivalent for men per se. We need to show men who perhaps don’t feel represented that they are equally valid,” he says.

Some answers are easier than others. Today, we’re all bombarded by mental health campaigns that implore us – particularly men – to talk more about our problems. While that’s a noble request, perhaps we need to start thinking more about why men feel they can’t talk about these issues; to ask why we are failing to build a culture in which people of all gender persuasions can feel empowered to raise their voice before it’s too late.

“It sounds really cheesy, but the first relationship we have is with ourselves,” Hadjiioannou tells me towards the end of our conversation. “If that relationship is healthy enough, that’s when we can start extending it outwards to relationships with other people.”

That work involves self-analysis, of course, but it also requires us to continue unpacking the wider values of a system that rewards our slavish commitment to uniformity while paying performative lip service to individuality. Maybe then we’ll start teaching future generations that “eye candy” should never come at such an eye-watering price.