I have never been busier,” says David Hockney, painter, national treasure, smoking advocate and fervent libertarian, now aged 85, cigarette in hand. He’s dressed in a newly tailored black corduroy suit, with a badge on each lapel saying “End Bossiness Soonest”. The word “Soonest” is his own addition, an insistent reminder to self.

Sitting at the kitchen table in his London studio, two packets of Camels at the ready, he explains his most ambitious art show so far in a 60-year career. It’s a 4D cinematic immersion experience using his paintings, photographs, opera sets, drawings, and collages, with music and voices (well, actually only one voice – his), all projected by 27 multi-focus cameras onto four 11-metre-high walls in a cavernous underground space.

Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away) is a hi-tech experiment with multi-perspective film, juggling sound, music, images – some animated – and space. It is a collaboration with Nick Starr, ex-National Theatre executive director and co-founder of The Bridge Theatre. And it’s likely to do for art what the musical Cats did for poetry, by introducing it to a new audience worldwide. Bigger & Closer is a reinterpretation of past works – “a sort of self-portrait among other things” – on show in the bowels of a building in Lewis Cubitt Square, north of St Pancras station, from 22 February.

Hockney believes that it will challenge Hollywood with its reimagining of the cinematic experience. “This is a new kind of theatre, a new kind of cinema, and it will attract people, a lot of people,” he declares, riffing on technology and the masses. His theory is that the use of pictorial images to attract mass attention began in churches, then died out (Delacroix being the last major commission by the Church in the 1870s) before cinema took over for about a century. Now the internet has rekindled an appetite for images on a vast scale. “For a hundred years, cinema attracted people, but that is over, as now you can watch films on a big screen in your home. This show of mine, you can’t. This, you have to go to. It should excite and make Hollywood sit up. It will be shown in LA and will get them thinking. I feel this is a new turn of the dial,” he says.

The 55-minute extravaganza of colour images screened on walls features beguiling perspective interlaced with folksily direct and professorial commentary from Hockney (aka the David Attenborough of the Art World) seductively explaining his mission to mesmerise through the joy of art. Think Walt Disney reinvented as a 21st-century art curator, making everything visually accessible and gorgeous. “Yes, joy and prettiness are part of my DNA, and always have been. I have always loved life and I still do,” he adds, that familiar Yorkshire drawl combined with a slight tang of LA and the tar of a million cigarettes. Unsurprisingly, this eternal optimist signs off all his emails “Love Life”.

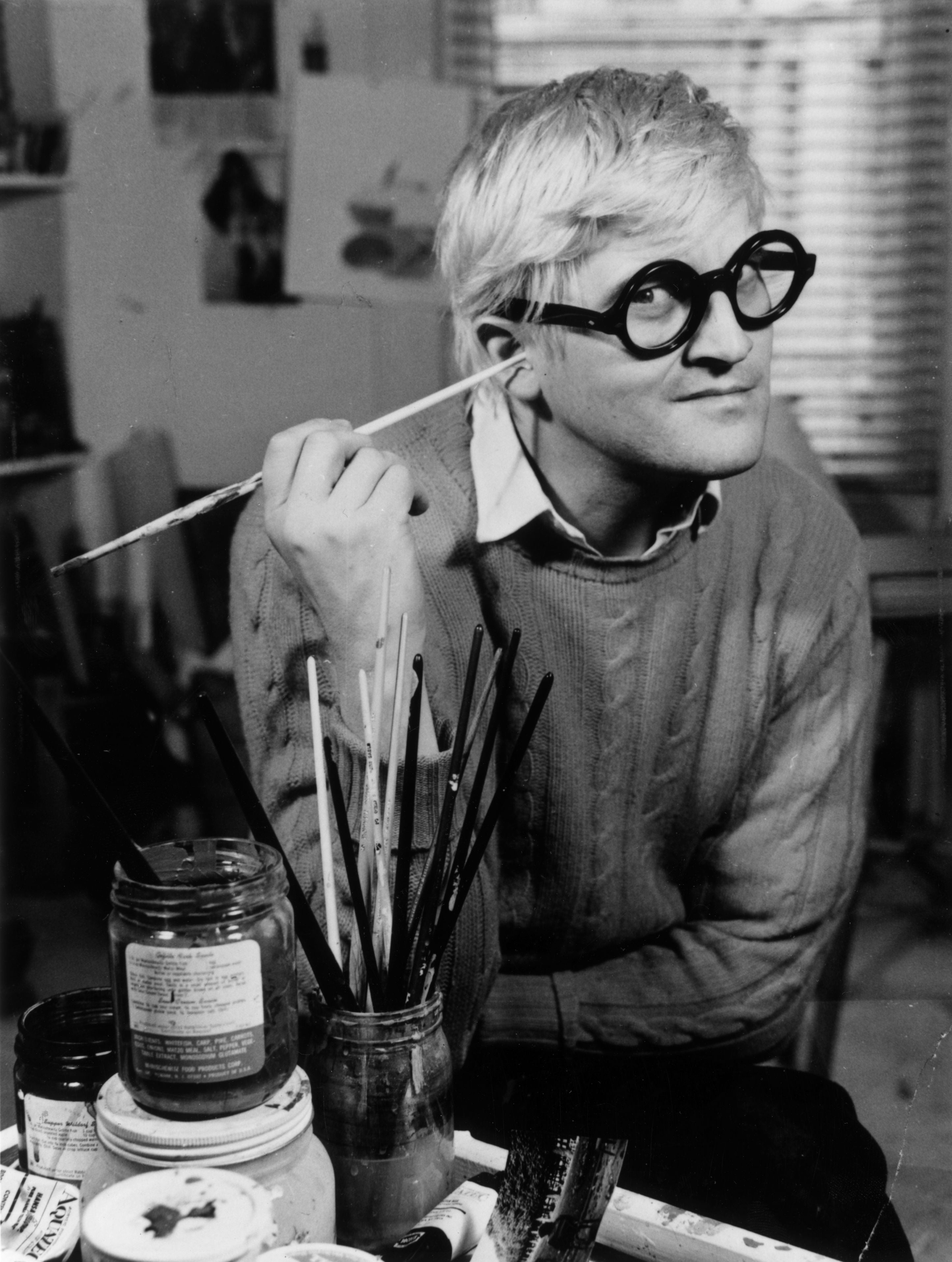

A dark blue bow tie is loosely knotted, light blue Crocs adorn his feet, and yellow-framed glasses occasionally slip from his nose as he brushes back a closely cropped grey mop, once a peroxide trademark. He is as infectiously enthusiastic as when I first interviewed him in his Notting Hill studio in 1976 for my school magazine. “I am feeling good, and that is because I still make pictures,” he says, speaking in thoughtful bubbles of conversation. “It gives me a better high than sex and also drugs. It is what has always turned me on. This [exhibition] shows a lot of my art in a completely new way. That is what I realised when I started this, and it keeps me going!”

He laughs a lot, a throaty gargle of shared amusement, relishing his new artistic adventure. His career has gone from dark Bradford portraits to sunny LA boys in blue pools, from palm trees to blossoming hawthorn, from shadow to light, from Yorkshire to Normandy, even to the Norwegian fjords. He explains how his energy comes from his art, before sweetly adding: “Actually, what keeps me going is JP. I couldn’t do any of this on my own. He looks after me and that gives me life.”

Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima is his boyfriend and collaborator of many years, a musician and photographer who surrounds and protects him with care and love. “We actually look after each other,” JP says, looking debonair and muscular as he enters the sitting room of their London house, rubbing David’s shoulder as he sits at the kitchen table – a wheelchair nearby. “I can still get around,” Hockney says. “I can get to the car. I just can’t walk that far, but we go where we want. I have still got my hands, my eyes and my heart. That is all you need. You don’t need your legs.” Pause, deep inhalation of a Camel. “Actually, I am 86 this year, you know,” he adds, with a twinkle in his eye. “I am always reading obituaries of people younger than me!”

But just as loving life to the full defines him, he is also not afraid of its end. “I don’t know how much longer I have. Probably not much. Then I will be in oblivion, but yet that might also be another adventure.” And he laughs again, giving off no sense of anxiety at the prospect of his own death. “I don’t know what will happen. It could be what I have described: an adventure. I don’t really do religion, although my mother always believed. I lost my faith when I was about 15.”

And so he talks on and on, irrepressible and ever curious, offering fresh and agile analysis: pulsating with life. “I don’t do regret. I do NOW. All artists do. I have seen my life so far as a great adventure, and am just so glad I lived in the second half of the 20th century. It was so much better than the first, with its two unbearable world wars. I was eight when the 1945 war was over. Rationing went on until 1953, all the time I was at Bradford Grammar School. You couldn’t buy sweets, only coupons. So life just always got better!”

I have seen my life so far as a great adventure

Not that it ever stopped him from campaigning for further freedoms, in his mission to protect or extend our liberties. “There is too much bossiness here, much too much. Everywhere smoking is banned, which is ridiculous. I have smoked for 70 years – I am still here! I can remember I would go on a Bradford bus when I was about eight and I went on top because you could see out at the front. I always wanted to look out and I still do. Inside the bus it was blue with smoke. I survived that. I am so glad I am not 20 today. Aged 20, I could smoke anywhere. On buses. On trains. In restaurants. There is a meanness of spirit about today and you get fed up with that. It is mad that the government taxes me for smoking and gives money to ASH (the anti-smoking lobby) – quite mad. They hate me at ASH.”

Hockney moves on to art, dancing (“I don’t dance”), sex (“Don’t you worry, I have had enough in my time”), religion (“I don’t do it”), watching the latest film (All Quiet on the Western Front), seeing his first opera for many years (The Magic Flute at Covent Garden), and snapping up some sharp new clothes (“I hate what men wear today – it’s just sports clothes, where is all the style?”). Hockney now wears only suits – even when painting. He was taken by JP to a tailor in Normandy, and ordered nine for winter and summer. Hockney close-up is more high-school energy than pension-age pauses. His mind whirrs and he is restless for the next thing. He doesn’t do pauses, and he doesn’t do dull. “I have just completed 40 portraits in France.”

Brand Hockney is universal. South Korea is putting on his new show, as is California. A Hockney show is always on somewhere in the world. The price of his paintings has topped $90m (£74m) – a 1972 work, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), sold for $90.3m in 2018. Every week an auction house, internet site or gallery somewhere sells a print, drawing or painting. He is the only truly global living artist, Britain’s greatest living export. In November last year, he had lunch at Buckingham Palace with King Charles for the Order of Merit, an annual gathering of the nation’s greatest minds. His Crocs, wheelchair and a new tweed suit caught the public imagination, natty sartorial touches that have kept him a fashion icon ever since 1960. He smiles ruefully at the Croc-kney headlines he inspired.

A cup of coffee stays untouched as he goes for the Camels and remembers a dashing portrait of his late friend the artist Patrick Procktor, whom he painted standing, cigarette in hand. The pair were once described as “the dandy twins of the art world”. Hockney recalls being at the long-closed Tooth art gallery for a show by Allen Jones (the Pop artist famous for his statuesque women in bikinis). “I remember Patrick looking at the paintings and saying, if there is one thing worse than homosexual art it is heterosexual art! He was always very funny.” More laughter. Yet Hockney is always deeply serious and ambitious with his art, breaking barriers, creating new language, pushing his imagination and equally importantly capturing the imagination of the public. His views on perspective have been the topic of PhD theses. His new show will be a blockbuster; tickets are already selling fast.

The film/art installation will last more than a year, as well as being staged around the world. It started when the filmmakers approached him at his studio in France. “I realised it was something new and exciting with the technology. That is why I did this – finding new perspectives. Something dramatically new.

“Only Klee, Klimt and Van Gogh have had this film immersion treatment, but they are all dead,” he notes, half triumphantly, half mischievously. “I am alive! I know it is going to be one of the biggest things in London.” And he is right.

Three weeks earlier, he and I are alone in the St Pancras space alongside 11 technicians working power decks. In his wheelchair, Hockney moves to different places to take in and edit the experience. For 55 minutes, we are surrounded by art, sound and movement. From Wagner to Mozart. From his journey through California’s San Gabriel mountains in the open-top car in which I was a passenger 25 years ago, to Hockney in the studio, boys diving in pools, operatic princesses in castles. It is the sensory equivalent of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang flying over the cliffs: belief is suspended as space and time and movement and perspective are thrown into a fantasia that stretches perception and imagination.

“It really is fantastic what they have all done, and it has been a team effort,” he says. “JP had the genius idea to include my opera designs. He said so few people have seen them compared to my paintings. It brings in things most people have never seen. It gave a new dimension. With Tristan and Isolde, you are with them on the boat, in the sea, on the castle. It sweeps people away into a new space and experience. It gives my art a new breath of life and a reinterpretation. And that, for me, is very exciting.”

Reinvention is part of Hockney’s progress, but always he returns to painting. “I am going to go back to my studio in Normandy, and will close the door and get back to work.” Back to the canvas and the brush. “Technology has always interested me, and really a brush is technology, a pencil is, just as the iPad was when it came along. I had already started using the iPhone in ‘twenty-o-nine’, and in 2010 I got an iPad, the first ever in Bridlington, and I started drawing on it straight away. Do I have a hunger always to do new things? Yes I do.” Another smile and a pulse of pleasure as he is so pleased still to be stretching his limits.

France, where he moved to and built a studio in 2019, was a creative catalyst for Hockney. “It is where I got a new lease of life. I embraced it. We have a five-acre field with a river running at the bottom. It is quite marvellous. I don’t go out much. I drive round the fields in a Toyota truck. We go to Paris a little. I went there to do Spring, and we stayed on.”

France is where I got a new lease of life. I embraced it

Hockney always has an eye on the future, but is equally vivid about the past. Opera is a constant in his show, and a permanent thread through his life. “Always opera excited me. I like pop music, but after David Bowie I don’t really know much about it. In America, on the radio, if you want pop music you have it on all day, and also with classical music. Music is segregated there. As a teenager, I was brought up with German music: Brahms, Mozart, Wagner – often with the Yorkshire Symphony Orchestra or the Hallé. It was always marvellous to me. I don’t really dance, as dance music is something else. And most of pop music is that, and I can’t hear it that well now. Music has been a central pleasure in my life.”

New hearing aids have improved his life. He sees technology as an evolutionary thread throughout history, from the camera obscura used by Renaissance artists to faxes, Polaroids, iPads and cameras. Print media he sees as fading, dying out. But he sees digital expansion. “Technology brings it in and technology takes it away,” he intones, almost like a high priest of art and invention. His next step, he admits, is unknown. He likes it that way, as it will mean another new adventure. Stepping forward, forging new ways, always finding beauty.

‘David Hockney: Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away)’ opens at Lightroom in London on 22 February