Spring is nearing and birds will soon start nesting in trees in backyards across Australia. The trees in our garden are now 40 years old – not old by tree standards, but old enough to be among the tallest in our suburb, offering refuge for local native birds.

When I propagated Monterey pine (Pinus radiata) seedlings for research in the mid 1970s, there were a few left over. I kept a couple, and one made a fine indoor Christmas tree for our young family in the early 1980s. My plan was to get rid of the tree but, after a few Christmases, the family was determined it would stay.

In the years since our tree, now in the garden, has grown to nearly 27 metres tall and almost 1m in diameter. It has become a favourite of many birds over the years and a nesting tree for ring-tailed possums.

A group of noisy but intelligent little ravens (Corvus mellori), have roosted in it, crowed from its lofty heights and battled others of the same and different species that have trespassed.

Over COVID lockdowns, I observed the curious behaviour of little ravens as they busily built their nests using the trees in my garden, and learned how they create a soft nest lining for their chicks. This spring you, too, can observe the delightful behaviour of birds as they visit your nearby trees and shrubs.

Little ravens in backyards

Monterey pine is an introduced species to Australia, and has significant potential to become a weed, so we regularly check for self-sown seedlings. So far our vigilance has paid off and there are no escapees in the parks, gardens and surrounds.

While I would never recommend its planting, we are going to make the most of its presence while we have it. Over the years the tree has provided great summer shade and some wonderful interactions with local wildlife.

Read more: Cockatoos and rainbow lorikeets battle for nest space as the best old trees disappear

The din when sulphur-crested and yellow-tailed black cockatoos make their visits to feed on cones has to be heard to be believed. The cockatoos drive the little ravens away as they enjoy the cones, but the little ravens keep a look out and return as soon as the cockatoos have finished feeding.

During lockdowns the avian demands, discussion and negotiations were a welcome and entertaining break.

Little ravens aren’t likely to rank high in the list of popular birds, but there is much to be impressed by when you study them.

Despite their name, little ravens aren’t actually that little, at over 40 centimetres tall. They are common across southern Australia and will eat almost anything, plant or animal.

They’re intelligent birds and great scavengers, capable of opening food containers, raiding bins and devouring road kill. They have adapted well to humans and so are found in backyards across the country.

Building cosy nests

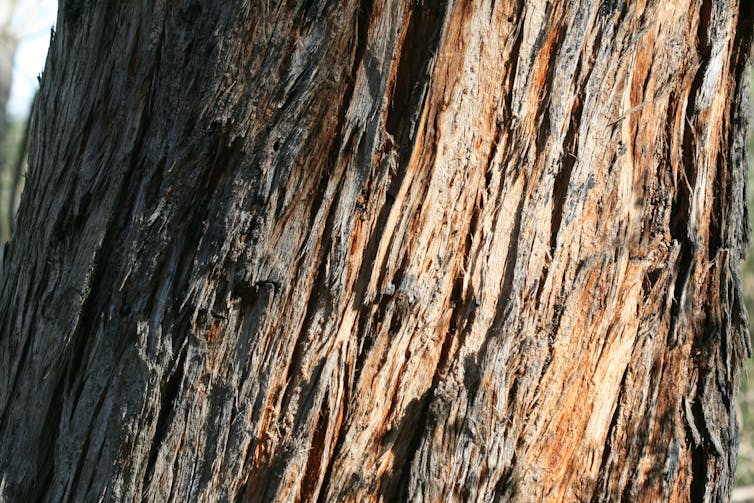

Another special tree in our garden is the messmate stringy bark (Eucalyptus obliqua). I grew it and hundreds of others from seed for research experiments in the late 1970s, and it comes from the Wombat Forest near Daylesford, Victoria.

Its spreading canopy provides fine dappled summer shade. And it’s almost inconspicuous white flowers cause the tree to hum from the visits of local bees, not to mention the visits of native honey eaters, such as the yellow wattlebird and the white plumed honeyeater.

Every spring for about 20 years I had noticed marks on the tree’s branches, and wondered what caused them. During lockdown, I observed little ravens peeling strips of the fibrous stringy bark from upper branches. These are private, unannounced visits without calls or fuss. You had to be alert to know the birds were there.

Many birds are expert home decorators. The little ravens know exactly what they’re after and where to find it, and harvest nest-building material from different parts of the tree.

Read more: Stringybark is tough as boots (and gave us the word 'Eucalyptus')

In their first visits, they gather material for the basic structure of the nest, made from twigs. Once in place, they strip long, coarse strings of bark from lower and larger branches in the canopy.

A few days later, the birds return to some of the younger upper branches where they collect fine, almost fur-like snippets of bark. These will provide an ideal fine soft inner nest lining for hatching raven chicks.

Observing birds in your own backyard

From my work with trees, I have come to appreciate some of the delicate and intimate relationships between fauna and flora and fungi.

I look for evidence of possum claw marks on heavily grazed trees and the damage to branches caused by the nibbling of the powerful beaks of sulphur-crested cockatoos. Now, I know the long strands pulled from the upper trunks and larger branches of messmate stringy bark are due to the careful work of little ravens lining their nests.

So at this time of the year, keep an eye out on both your garden plants and their avian visitors.

Look for birds darting, almost furtively, in and out of your trees, wisterias and rose bushes – they may have a nest within the foliage. Your prickly shrubs can afford protection to smaller birds and increase the chances of successful breeding.

Both native and introduced birds will be breeding in the next few weeks. And both native and introduced trees can be used by both for nesting.

Many of popular garden trees – such as wattles or introduced conifers – can host magpies and silvereyes. If you live near a creek, you may attract the superb fairy wren in a bottlebrush. And different finches may occur in your gum trees, roses or wisterias.

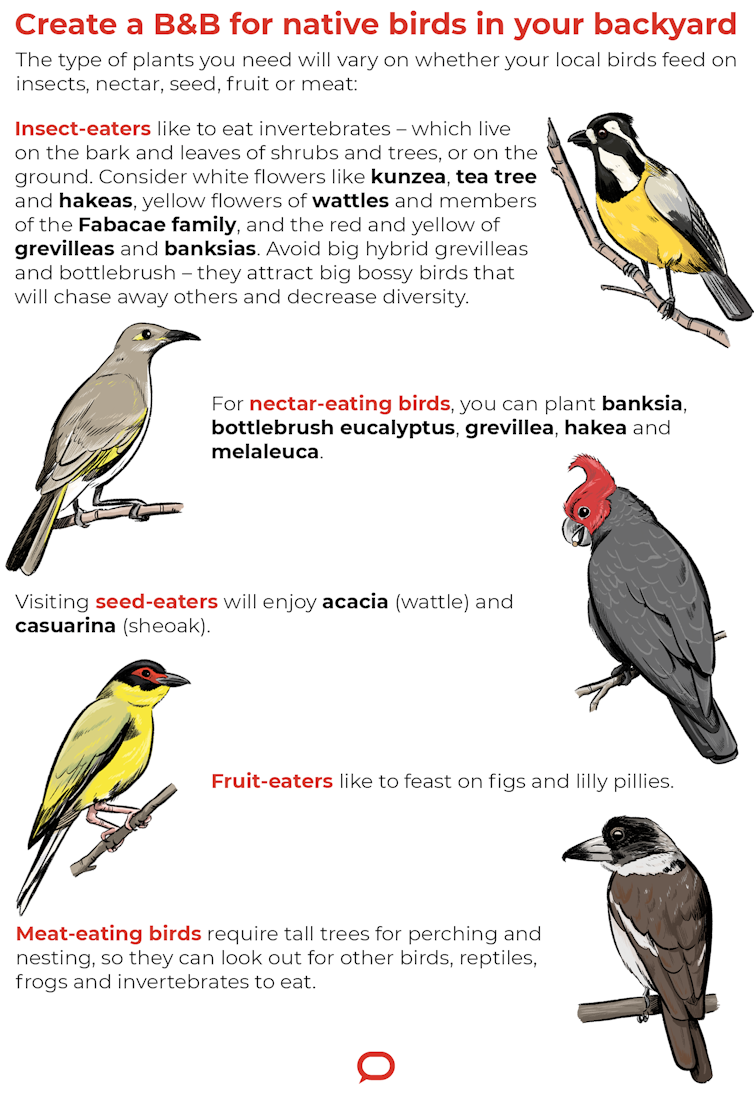

Native tree and shrub species with diverse flowering times can be beneficial to our native birds. They provide nectar and host native insects species in late winter and deliver a full bounty of resources in spring.

Trees with fine foliage and fibrous bark, such as stringy bark and some of the feathery-leaved wattles, are popular with birds at this time of year for nesting material.

This means your garden can be an important way to maintain local biodiversity. In a changing climate, we need all the diversity we can get!

Read more: B&Bs for birds and bees: transform your garden or balcony into a wildlife haven

Gregory Moore does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.