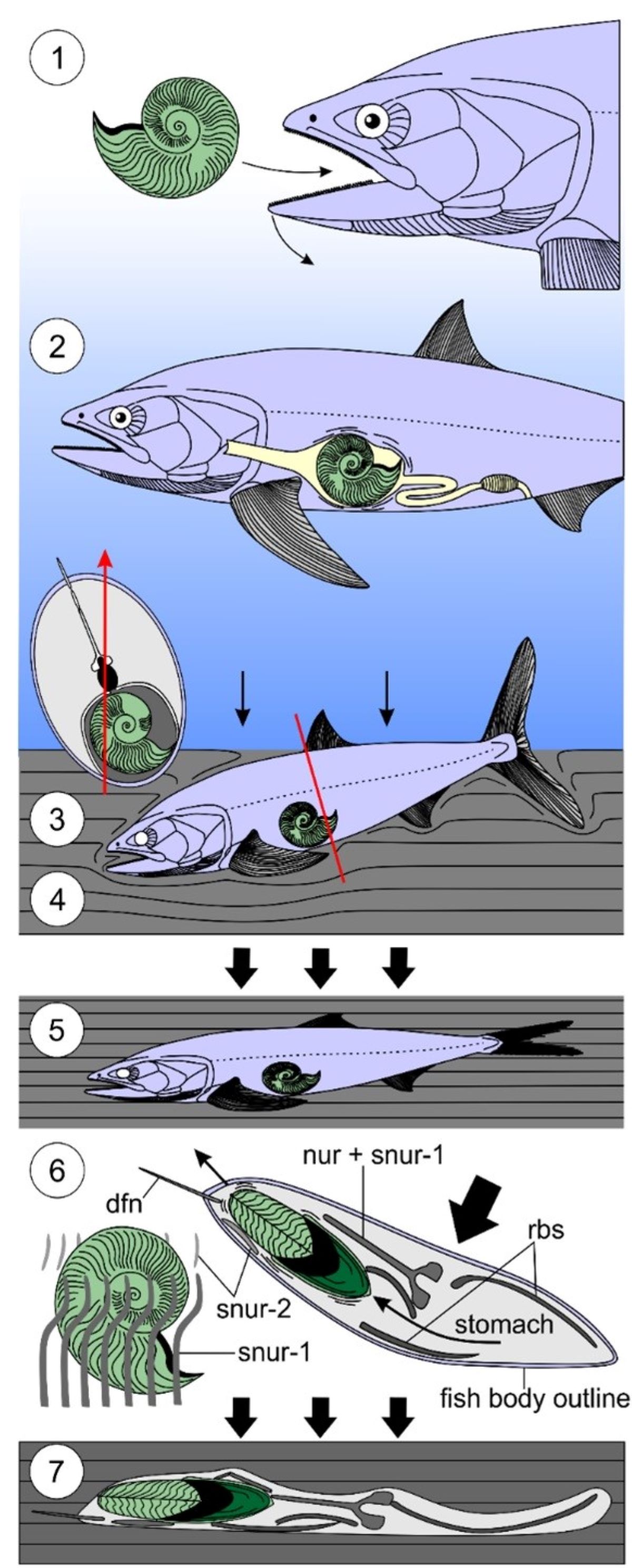

A dinosaur-era fish appears to have died after getting eyes too big for its stomach and ingesting a giant shell, researchers have found. The fish may have then choked to death on it, or the shell tore its stomach as it swallowed, the team said.

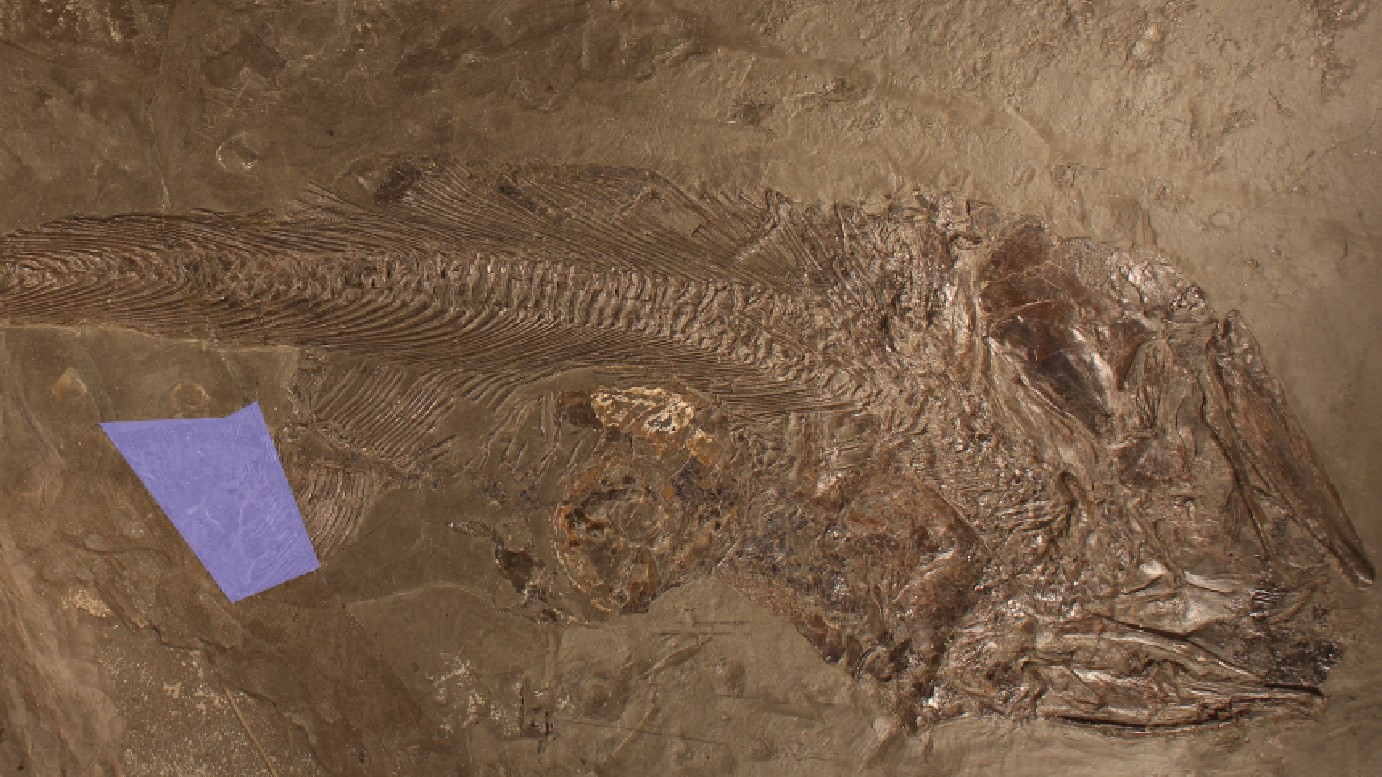

Scientists in Germany found the fish with the shell of an ammonite — an extinct group of marine mollusks — stuck inside it. This is the first time a fossilized fish has been discovered with an intact, large ammonite inside its body, Samuel Cooper, a doctoral candidate at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart in Germany, told Live Science.

The fossil was first dug up near Stuttgart in 1977 and stored in a museum drawer until researchers recently took a closer look and pieced together how this prehistoric fish died.

"If you want to make a really exciting discovery in paleontology, you don't always need to visit the quarry or a cliff or even go fossil hunting," Cooper said. "All you've got to do is just go to your local museum and ask to open some drawers." Cooper and his colleague published a description of the fossil on July 24 in the journal Geological Magazine.

Related: Terrifying megalodon attack on whale revealed in 15 million-year-old fossils

Around 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic (201 million to 145 million years ago), southwest Germany was covered in a warm, shallow sea that was home to giant marine wildlife like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs.

But hidden among those titanic animals was an array of smaller marine life, including Pachycormus macropterus — a sleek, tuna-like fish about 3 feet (0.9 meter) long. Paleontologists believe that Pachycormus fish ate soft foods like squids, Cooper said. But one day, one fish decided to change things up.

The fossil clearly shows the imprint of a 4-inch-wide (10 centimeters) spiral ammonite shell lodged up against the fish's spine. And for a fish of this size, that's likely way too big to swallow.

"I suppose it's equivalent of you and I swallowing a small dinner plate," Cooper said. He speculates that the fish may have confused the shell for a more edible bit of food, or accidentally swallowed the shell while eating around it.

Researchers previously knew that the museum held a fossilized fish with an ammonite, but they thought this pairing was likely a coincidence, Cooper said. Perhaps, for example, the fish and ammonite had simply fallen in the same spot and been fossilized next to each other.

But by closely examining the specimen, Cooper found that parts of the fish were on top of the ammonite fossil and other parts were below it — showing that the shell was inside the fish when it died.

In addition, some of the aragonite – a mineral that makes up much of the ammonite's shell – is remarkably well-preserved. Aragonite tends to break down in fossils, making it rare to find, Cooper said. But in this case, the fish's stomach may have provided a protective barrier for the shell and prevented total deterioration of the aragonite.

By piecing together the clues and finding out how these long-dead creatures lived and died, researchers can start to bring this Jurassic-era marine ecosystem back to life.

"For me," Cooper said, "it just paints a really interesting picture of what was actually going on."