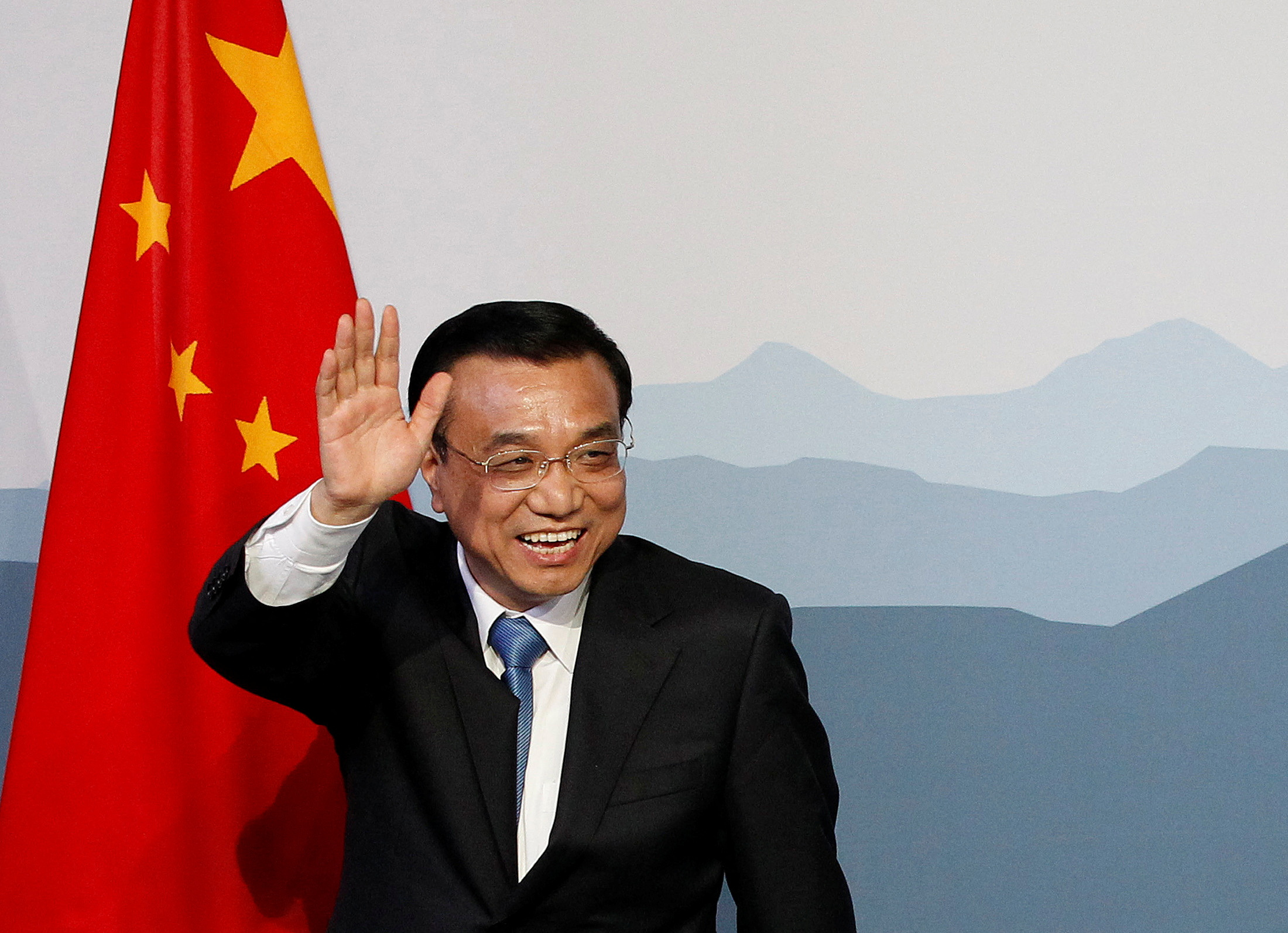

Li Keqiang, the former premier of China, has died of a heart attack, less than a year after stepping down from his post as the country’s second-highest-ranking leader.

“On October 26, Li had a sudden heart attack and passed away at 00:10 on October 27 [16:10 GMT October 26] after all rescue measures failed,” the state-run Global Times reported on Friday.

The 68-year-old, who retired in March, served two terms alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping, but towards the end of his career, was politically side-lined as Xi amassed ever-greater personal power over China’s government and economy.

In the hours after Li’s death, news reports were indexed notably low in media like People’s Daily and China Daily – both considered mouthpieces of the Chinese Communist Party – taking second or third place to articles on new infrastructure, foreign investment, and even astronauts.

David Bandurski, director of the China Media Project, said China’s leadership would probably want to take a “great deal of care” over the treatment of Li’s death, and how his contributions are remembered.

“We can see the official state media moving very slowly already, with the release of a very clipped notice only mentioning that his obituary is forthcoming,’ Bandurski told Al Jazeera. “High-level political deaths are never a personal matter in China. They are highly sensitive and treated as such because there is power and peril in remembering.”

Li’s tenure as premier and head of Xi’s cabinet proved disappointing to supporters at home and abroad who were hoping that a university-educated economist would open China’s economy even further.

Instead, his portfolio was eclipsed by the rise of Xi and a slide towards greater authoritarianism.

“Li hopelessly stood by as China took a sharp turn away from reform and opening. The wind was too strong,” Adam Ni, an independent analyst and editor of the China Neican newsletter, told Al Jazeera.

He said Li’s death, like his premiership, would be “forgettable.”

“The situation we are in now, this political moment, is nothing like the aftermath of the death of Zhou Enlai and Hu Yaobang,” he said, citing two of China’s most famous Communist Party leaders. “Their deaths catalysed instability and protest.”

They included protests in 1976 at the end of the Cultural Revolution and again in the spring of 1989 at Tiananmen Square. Li will have no such legacy, Ni said.

Reform frustrated

Li’s attempts to steer China’s economy through the COVID-19 pandemic ultimately took a back seat to a policy of “zero COVID” – leading to the kind of slow growth not seen since the height of the Cultural Revolution.

“His premiership took place in a context of China tightening the control of the economy and the society, and an era where security and ideology gradually overtook economic performance as the priority, which is well shown by China’s prioritisation of zero-COVID over economic recovery,” said Yun Sun, director of the China Program at the Stimson Center.

“He was a reformist that wasn’t able to pursue his reform agenda. I think his death reminds people of what he wasn’t able to achieve rather than what he was able to achieve,” she added.

Li was born in rural China in 1955 to a local government official, and like many leaders of his generation, he was a one-time “sent down youth” who spent the Cultural Revolution in the countryside.

Li was later able to return to his education and graduated from the elite Peking University, where he also became acquainted with pro-democracy activists during a period of political and economic opening in the 1980s.

That period came to a bloody end when Beijing sent armed troops into Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, to put down months of protests, calling for political and economic change and an end to corruption.

Li’s political and professional career survived the brutal crackdown.

As a member of the Communist Party, Li later aligned himself with the Communist Youth League and its patron, former Chinese President and Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao.

Hu was rarely seen in public after stepping down in 2013 and was humiliated last year when he was removed from an important session of the 20th Party Congress – a sign seen by foreign commentators as indicative of a “purge”.

In the months leading up to his retirement, Li referenced China’s mightiest rivers to stress his optimism that China would always move forward.

“Li said the flows of the Yellow and the Yangtze could not be reversed,” recalled Ni of a speech the then premier made in Shenzhen last year.

“He meant that the larger currents of history, of human progress that have been propelling China’s progress (as in the reform and opening era) can’t be reversed. Not by nostalgia for the past. Not by closemindedness. Not by policies designed to reverse some aspect of it. He may or may not be right. But at this moment, it does appear things can be reversed.”