It’s almost a bad pub-rock story – a band so good that someone said: “Stone the crows!” when he first saw them, thus supplying their new name. But since it was Led Zeppelin manager Peter Grant doing the naming, it’s suddenly much more worthy.

The event took place in Glasgow’s iconic Burns Howff bar and venue in 1969. Up until that gig, the band were called Power – a fitting title for a group that featured the larger-than-life talents of singer Maggie Bell and guitarist Leslie Harvey. A forceful character like Grant was the perfect match for the young couple, who’d made a life plan based on pursuing their musical dreams.

“Saturday afternoons in the Howff were the best time,” Bell recalls. “But it felt like ‘all dressed up and nowhere to go’, because they shut at two o’clock under the local rules. It was just getting to something in there and then the door shut.”

On that particular afternoon, though, the most interesting thing happened after the clock had struck two. “Peter had turned up in this big black limousine – I think it was the Lord Provost’s, because you didn’t get many of them in Glasgow. He’d come to see Leslie; he didn’t know I could sing, because you couldn’t hear me in the Howff.”

Negotiations with landlord John Waterson were swift. “John barred the door – ‘That band’s not going anywhere!’ Then it was: ‘I’ve got a few demands…’ Peter wasn’t having it: ‘You’re the guy who cleans glasses, aren’t you?’ and he shoved him out the way. I never went back to that pub.”

Power had been formed with keyboard player John McGinnis and bassist Jimmy Dewar after engaged couple Harvey and Bell had spent time touring US military bases in Germany – a 60s rite of passage that many musicians went through. Their plan was to go to London, and from there make it to the US, and they’d been saving money to fund their ambition, buying equipment including a reel-to-reel tape recorder to help them on their way.

Due to a last-minute lineup emergency by the band Cartoone, Harvey had been hired by them to play a US tour. The experience changed him so much that on his return Bell barely recognised him through his hippie clothes, wild hair and Lennon glasses. Outlining an updated life plan to her, they formed Power, and Harvey asked Cartoone’s manegement – Grant and Mark London – to check them out.

Within weeks they’d moved to London, living with Harvey’s elder brother Alex, who’d found drummer Colin Allen for them. When the band, now named Stone The Crows, entered Advision studios to record their first album, the music industry had found favour with the concept of bands writing their own songs – something none of the band had ever done. They used their friendship with fellow Glaswegian Lulu to get advice from her husband, Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees.

“Maurice said: ‘Leslie, you’ve got a guitar. Write the tune first and then put the lyrics to it’,” Bell says. “That’s exactly what we did.”

Allen became the band’s primary lyricist, confident he could do it because he’d always performed well in English compositions at school. While their 1970 quick-hit, self-titled debut album was part covers, the B-side was the ambitious 17-minute multi-part piece I Saw America.

“I wrote that because of my experiences in America on tour with John Mayall,” says Allen, who was older and more experienced than the others. “The ‘little girl from Detroit city’ was a girl called Nancy, who I met in Miami. I went to a love-in with Mick Taylor. Those were actual things I experienced that I put down on paper.”

With Grant behind them, within a year of signing their deal Stone The Crows toured the States. Bell recalls struggling to connect with audiences who were bewildered by a white woman possessing the vocal power she delivered. “The first night, in Alabama, not one person clapped in the audience. I said to our roadie: ‘Go and buy a couple of planks and make me a screen to put in front of the microphone.’ So when the lights came up, I was behind the screen doing a song. After the first song, when the applause was going, I came out from behind the screen and went: ‘Okay, can we carry on here?’”

Back in London, Harvey and Bell lived in a flat round the corner from Harrods and continued to work on their plan. Stone The Crows’ second album, Ode To John Law, also released in 1970, was another laudable but flawed attempt at capturing their live magic in the studio.

“The best recordings we ever made were the live things for the BBC,” Allen asserts. “Forget all that studio shit. Mark [London] gave us our head because he believed a lot in Leslie. But people were always trying to make things sound more commercial than they were.”

But Bell argues that their studio work was “pretty good considering how new we were at it”.

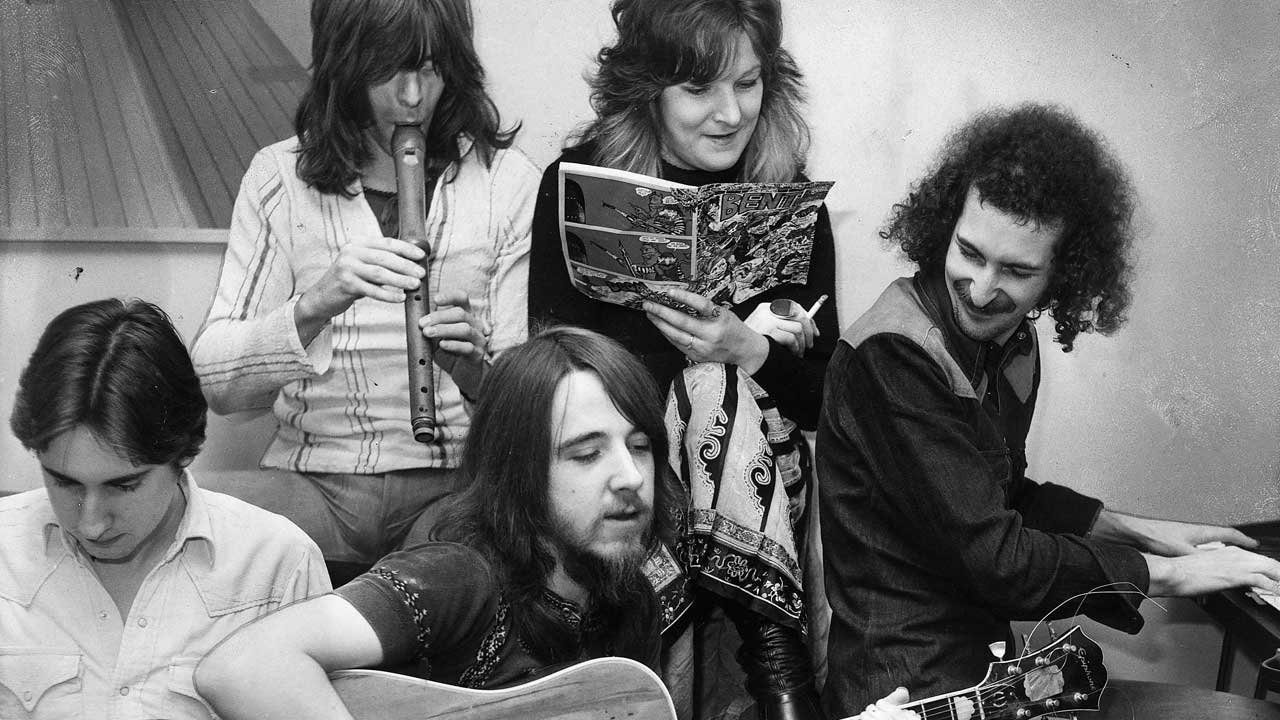

Meanwhile, life on the road had begun to tear at the band’s relationships. Harvey and Bell remained a strong partership, but Allen says McGinnis’s drinking started to grate, culminating when he drunkenly told Nazi jokes to a group of German promoters in a restaurant. He and Dewar were soon out of the band, replaced by Ronnie Leahy and Steve Thompson respectively.

“I liked the first incarnation with Jimmy and John better than the second incarnation,” Allen says. “I liked the music that the first band played more. It became a little more ordinary later. But the Crows was still one of the best bands I played in. It was a blues-based band, but it was a bit proggy as well. We went a little bit further than the usual bloody twelve-bars.”

It could be argued that the new line-up just needed more time to settle in, with the latest members having no experience of the band’s rise. Nevertheless, the Crows’ live performances continued to be acclaimed for their attitude and energy, with Harvey calling the shots and Bell providing the focus.

Their third album, 1971’s Teenage Licks, demonstrated an improved control of power and groove in Faces and I May Be Right I May Be Wrong, but also marked their continued interest in going off the rails in Mr Wizard and One Five Eight. With three of its nine tracks credited to Stone The Crows rather than specific writers, it seemed as if the band had weathered the storm of the line-up change, with the promise of greater work to come.

But fate intervened, in a tragic manner, when Harvey was electrocuted and died on stage at the Top Rank in Swansea on May 3, 1972. He was the only one in position on the stage. “It was a fluke,” Bell says. “We were standing at the side of the stage; we hadn’t even started yet. Leslie said to the audience: ‘There’s a technical hitch,’ and he touched the microphone and the guitar. And that was it.”

“We heard this deep humming sound,” Allen adds. “Leslie had the microphone in one hand and his guitar in the other, they kind of went together and then like an arc-shape appeared. I was up really quickly and kicked the guitar out of his hand as he was lying on the floor. I mean, talk about a tragedy. Leslie wore a dental plate, and one of the first-aid people had given it to Maggie. She said: ‘Can you go and get rid of this?’ I walked out the back of the ballroom and chucked it in a dumpster. You don’t know what else to do. I threw away the last of Leslie Harvey.”

Bell believes she was in shock for several years afterwards. “But I thought to myself: ‘Am I going to give all this up and go back up to Scotland and have two kids?’ I mean, this was a dream we’d planned. Peter said there would be no legal problems if I didn’t want to carry on. I said no, there was a plan. I was going to make sure that I finished the journey. I’m seventy-six years old, I’m still doing it. I mean, the body’s falling apart, but the voice is still fabulous!”

The challenge of replacing their leader was a huge one. But as Stone The Crows began working towards their first show without Harvey, Fleetwood Mac icon Peter Green appeared on the scene.

“I picked him up from the station,” Bell recalls. “He stayed in Ronnie’s basement for four or five weeks. It was kind of a rehabilitation centre. Ronnie and his wife fed him and kept him. We all took care of him, and the rehearsals went quite well. And then the night before the show, he calls up and he says: ‘I can’t do it. You’re going to be too famous. I don’t want to be famous.’ What the hell do we do now?”

Harvey and Bell were friends with Yes guitarist Steve Howe and he agreed to help out. “Steve stayed up all night, learning the songs, and saved us,” Bell says. “I can’t even remember going on stage. It was just a blast. The audience were so supportive and Steve did us proud.”

With the possibility of things being back on track, the band settled on guitarist Jimmy McCulloch as their new member.

“We played some great gigs with Jimmy,” Allen says. “He had great flair, but he wasn’t the kind of leader that Leslie was. There was a big difference in the kind of music they liked – I liked what Leslie had liked – but they were both great at what they did.”

Harvey’s final recordings came out on Stone The Crows’ fourth album, Ontinuous Performance (the title inspired by a broken venue sign), released four months after his death, and included two guitar tracks from McCulloch. The record closed with Sunset Cowboy, a personal tribute to Harvey.

“We’d been rehearsing in Devon and the studio was a stable as well,” Allen says. “So we thought let’s go out and ride a horse. And it was kind of late in the day. So Sunset Cowboy was a reflection of how I saw things at that time, you know? And it was dedicated to him.”

Despite Ontinuous Performance entering the Top 40, and Bell being voted Britain’s best female vocalist in a Melody Maker poll, the album and its associated tour left Bell with the feeling that it “was never going to work out”, citing “attitudes” that she doesn’t feel the need to revisit. Allen feels that industry politics was at play, and a disagreement with Leahy may have been used as a lever to split the band.

“I think for many of those months preceding the break-up, Peter [Grant] and Mark [London]were getting together and talking about getting a deal for Maggie – which is what happened,” Allen says. “I think Ronnie had a bit of an upset with Mark or with somebody, and the next thing I knew the band had broken up. It was a real surprise.”

What could have been is illustrated in several of the members’ careers. McCulloch went on to join Paul McCartney’s Wings; Dewar fronted Robin Trower’s band; Leahy played with Nazareth, Steve Howe and Jon Anderson; Allen added Focus to his CV, which already included John Mayall, Mick Taylor, Bob Dylan and many others.

The drummer believes Stone The Crows were “not necessarily” doomed. “We played lots of gigs which were really successful,” he says. “I think the management were just waiting for a chance to dump the rest of us sign a big contract with Atlantic for Maggie – which is basically what they did. Money, man. Fucks everything up. Unfortunately it didn’t do that much for Maggie. She’d have been better off staying in the band.”

Bell and Allen reunited in the British Blues Quintet from 2006 to 2013. “It’s incredible the number of Stone The Crows albums Maggie and I had to sign when we were on the road with the Quintet,” Allen says. “It’s great those albums are out there and still being listened to.”

Despite the tragedy of Harvey’s death, Bell – who released two solo albums after the split – thinks warmly of the band’s four-year trip. “We did the best we could,” she laughs when asked to sum it all up. “I was a friend of Peter’s till the day he died. He was really a wonderful man, and I know he did everything he possibly could for the Harvey family when Leslie died. No one ever fucked me over. Peter taught be to be strong. The only way you get fucked over is if you let someone do it. So don’t!”

This featured was originally published in Classic Rock 290, published in Summer 2021.