At 60, the age most people start contemplating retirement, Leslie Phillips took the biggest gamble of his life, leaving behind the lounge lizard and “silly ass comedy” roles that had made his name (and fortune) in order to pursue more personally challenging and serious work. The result was a triumphal late flowering of creativity that included roles for Steven Spielberg and the Royal Shakespeare Company, all of which marked him out as one of our most overlooked character actors, a fact recognised when he was awarded an OBE in 1998 and given a CBE in 2008.

Phillips’s reputation for broad comedy had always obscured his serious acting ambitions, belying a theatrical career that goes back to 1935. It was his mother, answering a newspaper advertisement, that saw Phillips accepted at the famous Italia Conti stage school aged 10, launching a career as a child actor that was born more out of economics than desire.

With his father dead and his mother struggling to raise three children, any extra income was welcome. Aged 13, Phillips was in the London Palladium production of Peter Pan opposite the great Sir Seymour Hicks as Captain Hook and by 14 was touring full-time around the provinces, sharing the stage with such luminaries as John Gielgud and Anna Neagle. Working at the Haymarket Theatre as a call boy when war broke out, Phillips also acted as fire-watcher by night behind the Phoenix Theatre, often having to put out incendiary bombs.

Commissioned into the Royal Artillery, Phillips was immediately transferred to the Durham Light Infantry. Having seen active service in Europe, the stress of constant bombardment was too much and he was hospitalised with a nervous breakdown. At least the army was responsible for his trademark languid bounder’s drawl, so famous that late in life he could still call up Harrods store and be recognised as soon as he opened his mouth to say hello. Looking as he did every inch officer material, Phillips was promptly made one and felt compelled to not only behave as officers did, but also to talk like them too.

Akin to his comedy compatriot Kenneth Williams, Phillips’s debonair public persona and immaculate vowels disguised a working-class background, born as he was on 20 April 1924 in Tottenham, close to the football ground.

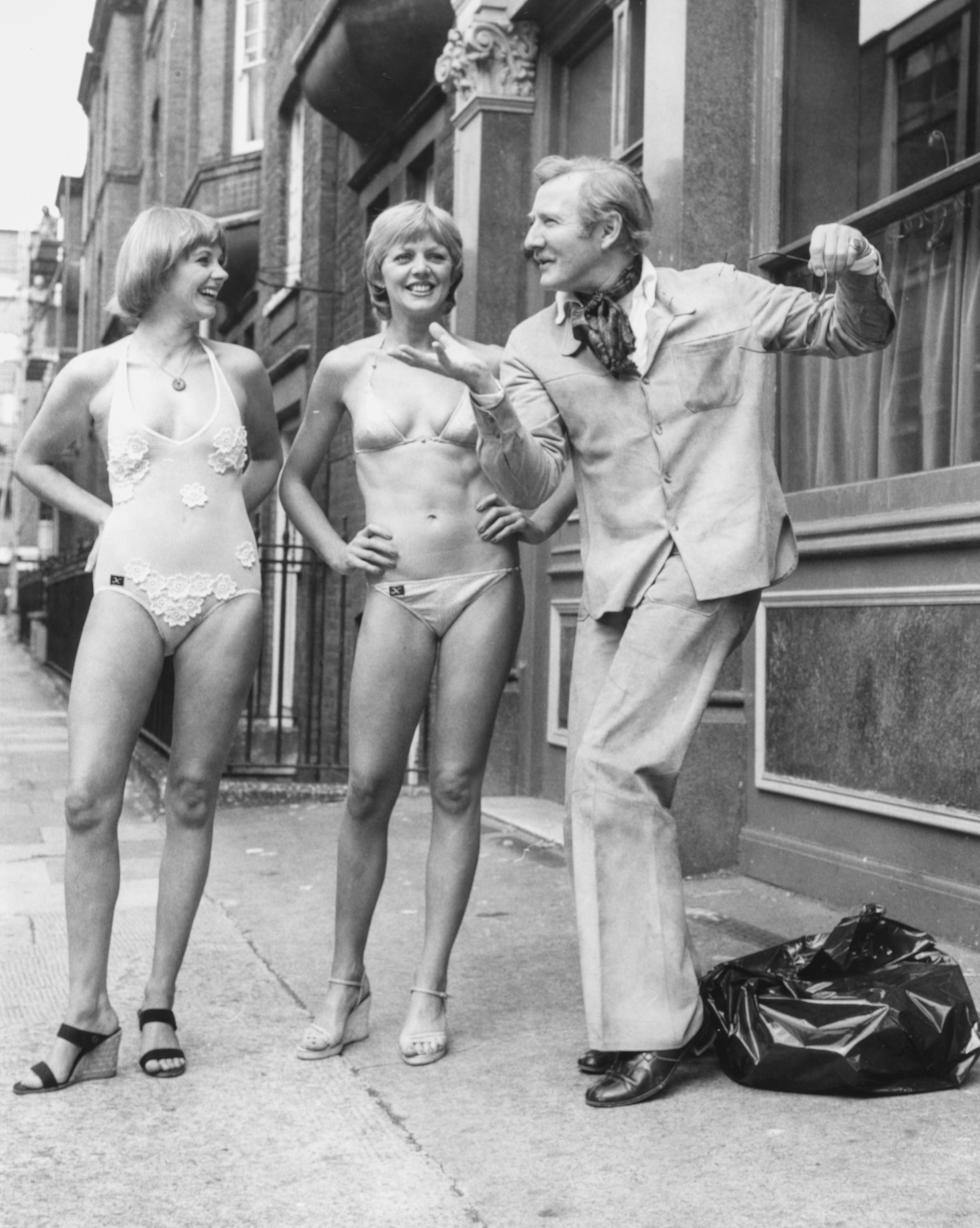

After the war, Phillips returned to the stage and got his big break in a revival of Charley’s Aunt that set him on his way, but it was the arrival of the long-running BBC radio serial The Navy Lark that did much to formulate his chinless wonder persona in the minds of the public. This was further solidified with roles in the Carry On and Doctor movies and numerous Whitehall farces where he was required to do nothing more erudite than hide in wardrobes or drop his trousers. There was also the obligatory period in Hollywood, but Phillips turned his back on a potential career out there because he missed London too much, the city he called home all his life.

During the Fifties and Sixties, Phillips seemed never to be out of work, being involved in practically every aspect of the business from acting and directing to producing and investing. It was a workaholic schedule partly fuelled by a deep-seated fear of poverty. One of his keenest childhood memories was seeing his mother crying when she looked in her purse.

Even after suffering a stomach haemorrhage, he persisted in continuing to star in a BBC sitcom against doctor’s orders, being ferried to and from the studios from his hospital bed in an ambulance. Another time he literally passed out on stage from exhaustion. His understudy, Nigel Hawthorne, was preparing to take over when a recuperated Phillips brushed him aside saying, “not on your Nelly”, and after a swift brandy bounded back on stage.

Away from the limelight, Phillips was a polite and gentle family man who enjoyed the occasional adept flutter on the stock market. He was a name at Lloyds for more than 20 years, though was shrewd enough to get out before the infamous market crash. His first marriage to actor Penelope Bartley lasted 17 years until it was dissolved in 1965 due to his adultery. They had four children, two sons and two daughters.

Fearful of another marriage failure, it wasn’t until 1982 that he committed again, to actor Angela Scoular when he was 56 and she was 36. This second marriage arrived at a fallow period in Phillips’s career when jobs were hard to find. He even resorted to suing his agents for breach of contract for not finding him work. He lost the case. The worst was to come when his 92-year-old mother was mugged outside her home and died several months later as a result of her injuries. It was an incident Phillips was to call the biggest tragedy of his life.

Concerned always about extending himself and the quality of the work he was doing, it was now that Phillips bravely decided to bury once and for all his caddish image and to move away from shallow comedy to more serious drama. “I made a conscious decision, not to avoid comedy, but to avoid anything that smacked of crap.”

There followed the predictable period of inactivity where he was presumed to be either dead or retired. His professional reincarnation began when he was cast opposite Joan Plowright in Lindsay Anderson’s production of The Cherry Orchard. No less a luminary as Sir Laurence Olivier phoned Phillips to compliment him on his performance.

Another success was his role in Peter Nichols’ Passion Play, which Phillips later contested was the finest theatrical production he ever appeared in. Suddenly critics who once never had a serious word for Phillips now found themselves acclaiming him.

There was also a late bloom of offers to play character roles in prestigious films such as Scandal, where he was the duplicitous Lord Astor, Out of Africa and Empire of the Sun where he went on a strict diet to play an emaciated POW. Phillips found himself so in demand that when Sir Anthony Hopkins asked him to appear in August, a Welsh-set film version of Uncle Vanya, he was forced to turn down Sir Peter Hall’s offer to play Polonius in Hamlet at the National Theatre.

But the stage remained his first love and he was a memorable Falstaff in the RSC’s production of The Merry Wives of Windsor at the Barbican in 1997, the year he received a lifetime achievement award at the Evening Standard British Film Awards.

Even aged 75 he was looking for fresh challenges, such as performing in a one-man show at the Edinburgh Festival, a decision that perfectly reflected his desire to move with the times and not to contentedly rest on dated laurels.

The actor also reached a new generation when he voiced the sarcastic Sorting Hat in the Harry Potter movies. His death – which comes two years after Barbara Windsor’s –leaves Jim Dale as the last surviving regular from the Carry On films.

Leslie Phillips, actor, born 20 April 1924, died 7 November 2022