Lemmy lit another cigarette, blew smoke in my face and put it like this: “Life has a funny way of not paying attention to you. I wanted to do the British version of the MC5, simple as that,” he shrugged, referring to the American punk-metal legends who recorded such classics as Kick Out The Jams. “If I could have joined the MC5, I would have. But they were in Detroit and so I formed my own version instead – called Motörhead. Only we weren’t called that originally. And I wanted it to be a five-piece band – and we weren’t that either. The only thing I got right was that I wanted the music to be fast and vicious, just like the MC5.”

In fact, if Lemmy had really had his way, he might never have formed his own band at all. In keeping with Motörhead’s enduring reputation for being one of the most, well, awkward of bands, their story actually began with an ending – in this case, Lemmy’s sacking, in 1975, from his previous band Hawkwind. As he confesses now, “I would never have left Hawkwind if I hadn’t been fired.”

Ifs, buts, maybes… Lemmy and Motörhead’s long career is full of them. Boundary-stretchers, risk-takers, non-conformists… it’s why we love them – and why, perhaps, the surprisingly strait-laced music business has always had such a hard time dealing with them. Lemmy has simply never followed the rules. Not even as the schoolboy son of a vicar. This, after all, is the guy who was thrown out of Hawkwind – inventors of space-rock – for being, as he puts it, “on the wrong drugs”.

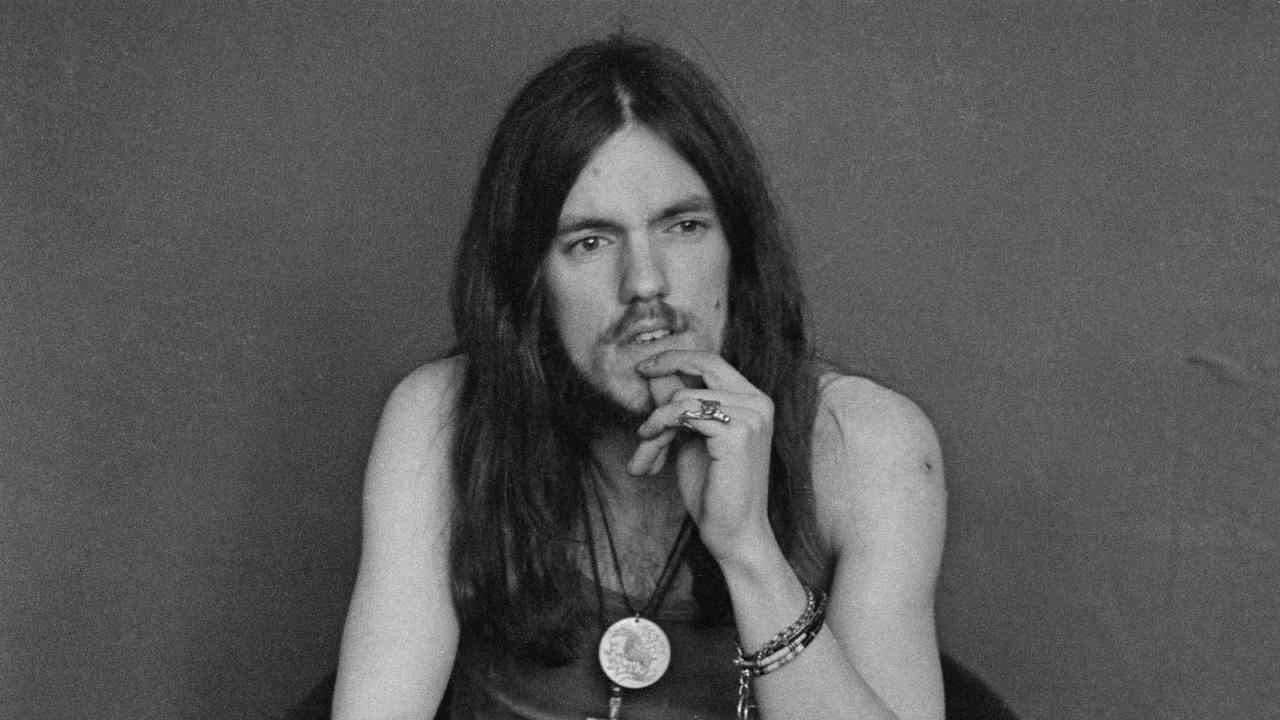

Lemmy was born Ian Fraser Kilmister in Stoke-on-Trent, on Christmas Eve 1945, and he was brought up in the Shropshire hills. His father was an RAF pastor who Lemmy would later describe as “a weasel of a man with glasses and a bald spot” – and who walked out on his young family when his son was three months old.

Lemmy – a nickname he acquired in the Hawkwind days after his habit of collaring everyone he met to “lemme [lend me] a fiver” – was just four when the local dentist decided to remove 10 of his teeth without anaesthetic. He wasn’t much older when he decided he preferred his own company to that of the other kids at school. He was eventually expelled for “whacking the headmaster round the head with his own cane”. He had worked, briefly, at the local riding stables (“I was very big into horses”), and at the local Hotpoint factory. But by then, “I’d heard Little Richard and it was all over”.

He knew he wanted to play guitar, he says, “the first time I saw Oh Boy! [the 1950s ITV version of Top Of The Pops] and saw all these birds screaming”. The first record Lemmy remembers buying as a kid was Tommy Steele’s Knee Deep In The Blues. With the aid of Bert Weedon’s Play In A Day book and his mother’s old Hawaiian guitar, he learned to play “well enough to impersonate Ricky Nelson”.

In 1963, aged just 17, Lemmy decided to “strike out for the big city”, hitchhiking to Manchester, where he got a gig playing guitar in the Rocking Vicars, and for the next two years “lived the life of bleeding Riley!” Part covers band, part cabaret act, the Vicars “were one of those bands nobody down south ever heard of but who were huge up north. We all had Jags. I had a Ford Zephyr 6, which was big news in them days.”

Frustrated, eventually, by the band’s lack of ambition, Lemmy came to London in 1967, where he shared a flat with Noel Redding and worked for £10 a week as a roadie for Jimi Hendrix. “I used to score acid for him,” he says with undisguised pride. “I’d get 10 hits and he’d take seven and give me three. My first tour was a co-headline with The Move, plus Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd, Keith Emerson’s The Nice, and some others. It was like the Rocking Vicars to the power of 12. I mean, it was fucking madness…They say acid doesn’t work two days in a row. But if you double the dose it does.”

But when Jimi left for America, Lemmy was laid off. He was “dealing dope in Kensington Market” when he first met a 25-year-old miscreant named Michael Davis, aka Dik Mik, and “discovered we had this mutual interest in how long the human body can be made to jump about without stopping”.

The other thing they had in common was monumentally loud, psychedelic rock music. Originally brought in to drive the van, Dik Mik had recently talked his way into becoming a full-time member of Hawkwind by building a contraption he called an ‘audio generator’: made, he liked to claim, from the parts of an old vacuum cleaner; in reality, a customised ring modulator.

Or as Hawkwind founder-guitarist Dave Brock recalls: “We didn’t know what it was – it just used to make this sort of whooshing sound, which fitted what we wanted to do at the time.” Which was? “To make music that was like the aural equivalent of an acid trip.” Or as the Melody Maker said of Hawkwind’s 1971 album In Search Of Space: “The band’s claim that it is specifically aimed at dope freaks certainly seems to be valid.”

Recalled now as a sort of poor man’s Pink Floyd, as Brock says, “We could have been as big as the Floyd. A few times the openings were there. But it’s whether you’ve got a torpedo mechanism to bring it all down, and you think, fuck that, you know? Once you do that, you’re on the other side. Hawkwind was always on the other side of everything.”

Formed in 1968, Hawkwind comprised a series of “captains”, as Brock, a former busker, called them. People like co-founder Nik Turner, the “musically naive” sax player and self-appointed keeper of the Hawkwind flame, insisting on the many free gigs they did. He was the magnet for most of the other captains, like his old cohort from Margate, Robert Calvert, the manic-depressive genius who helped conceptualise Hawkwind’s “broken spaceship”; Barney Bubbles, whose lysergic images of space storms, Stonehenge and naked breasts adorned all their early albums; writer Michael Moorcock, who would routinely turn up at Hawk shows and read his dementedly futuristic poetry; and Stacia, the 22-year-old statuesque beauty whose Amazonian-like figure would transfix audiences as she danced naked with the band, her undulating hips and battleship breasts daubed in Bubbles-esque designs.

By 1971, when Dik Mik joined, there was also drummer Simon King and synthesiser player Del Dettmar, but nobody who stood out quite like their newest recruit: the 25-year-old with the Iron Cross dangling round his neck, and whose ashtray voice would adorn Hawkwind’s solitary hit single, Silver Machine, in 1972. The last of Brock’s captains to arrive, and the first to be asked to leave, Lemmy was destined to be the member of the band non-Hawkwind fans would always remember best from those days.

For Lemmy, these were halcyon times. Recalling the night the band recorded Silver Machine live at the Roundhouse, he says: “Me and Dik Mik had been up four days, right, on Dexedrine spansules, so we’re pretty well bent by now anyway. But we had this gig at the Roundhouse so we had a couple of Mandrax to calm us down. Then it got a bit boring so we had two black bombers each. And then we got in the car and Dik Mik wasn’t enjoying driving but he wouldn’t let you do it and so we were following the kerb up there, you know, very slowly. He said things kept sticking in his eyes from the right…

“We get to the Roundhouse and somebody comes in with a lot of bombers and we take 10 bombers each. Then someone comes up with some Mandrax and we were getting very twisted up by now and so we had at least three Mandrax each to calm us down again. Then somebody came up with some cocaine, fucking big bags of it, and so we thought we’d have some of that. And we were all blasted out of our heads from smoking dope as well. And acid. People were producing acid and mescaline. So we all had some of that.

“By the time we come to go on stage, right, me and Dik Mik are stiff like boards. I said, ‘I can’t move, Dik Mik, can you?’ He went, ‘No. It’s great, isn’t it?’ I said, ‘What are we gonna do when we can’t play?’ He said, ‘They’ll think of something…’”

Silver Machine was mixed straight off the desk by future Stiff Records supremo Dave Robinson, and originally had Bob Calvert, who wrote the lyrics, on ‘spoken-word’ vocals.

Hawkwind manager Doug Smith later took Lemmy into Morgan Studios to re-record the vocals and remix the track himself.

“Lemmy just had the best voice for it,” explains Doug. “But, of course, Bob was not pleased when he found out.” In fact, Bob, who was bipolar and had actually been sectioned for 28 days, had no say in the matter. “My decision, I’m afraid,” says Doug.

According to Lemmy, “they hated that” when Silver Machine became a hit with his vocals. “My picture on the front of the NME without them – the one who took them filthy speed drugs…”

If the No.3 chart success of the Silver Machine single represented Hawkind’s and Lemmy’s biggest high – along with the follow-on Top 10 success of their double-live Space Ritual album – the comedown came quickly. Busted on the Canadian border, en route to a show in Toronto, in May 1975, for possession of cocaine (a felony later downgraded to a fine when it turned out it was amphetamine sulphate he was carrying, not then actually illegal in Canada), Lemmy has always maintained that the bust “was just an excuse to get rid of me”.

According to Lemmy, “The band was split into the speed camp and the psychedelic camp. Me and Dik Mik were the untouchables because we liked speed.”

Speed, Dave Brock would concur, was regarded as “poor show… Irksome, as Bob used to call it.”

Lemmy claims now that the only reason the band even put up the money for his bail was because “they couldn’t get [Pink Fairies bassist] Paul Rudolph over quick enough to do the show in Toronto. So I did the show and at 4.30 in the morning I was fired.”

Lemmy later claimed that he wreaked his revenge on Hawkwind by “coming home and fucking all their old ladies… Not the ugly ones, of course. But at least four. I took great pleasure in it. Eat that, you bastards.”

He got his real revenge, though, by forming a band that would go on to even more success and critical renown than Hawkwind, to be called… Bastard.

There has since been some ‘conjecture’ over who renamed the band Motörhead – American slang for ‘speed freak’, and the title of the last recording Lemmy made with Hawkwind, written on that fateful final tour, and released as the B-side to the 1975 single Kings Of Speed.

Their former manager Doug Smith claims it was he who chose the name. “I just thought we couldn’t send out a press release with the name Bastard, so I took it upon myself to rename them after the song Motorhead, which was great and really sort of summed Lemmy up.”

This is something Lemmy staunchly denies. “It’s one of the best names of any rock’n’roll band ever. I wrote the song, I agreed to the name so the decision to name the band, that was mine.”

What no one can deny was that it was the start of one of the most legendary rock bands of them all. Not that it seemed like that at the time. Lemmy recalls “incredible poverty, living in squats. This bird we knew called Aeroplane Gaye used to work under a furniture store in Chelsea, and if anyone quit early, we’d all dash down there and rehearse. We were struggling for a long time with no bread.”

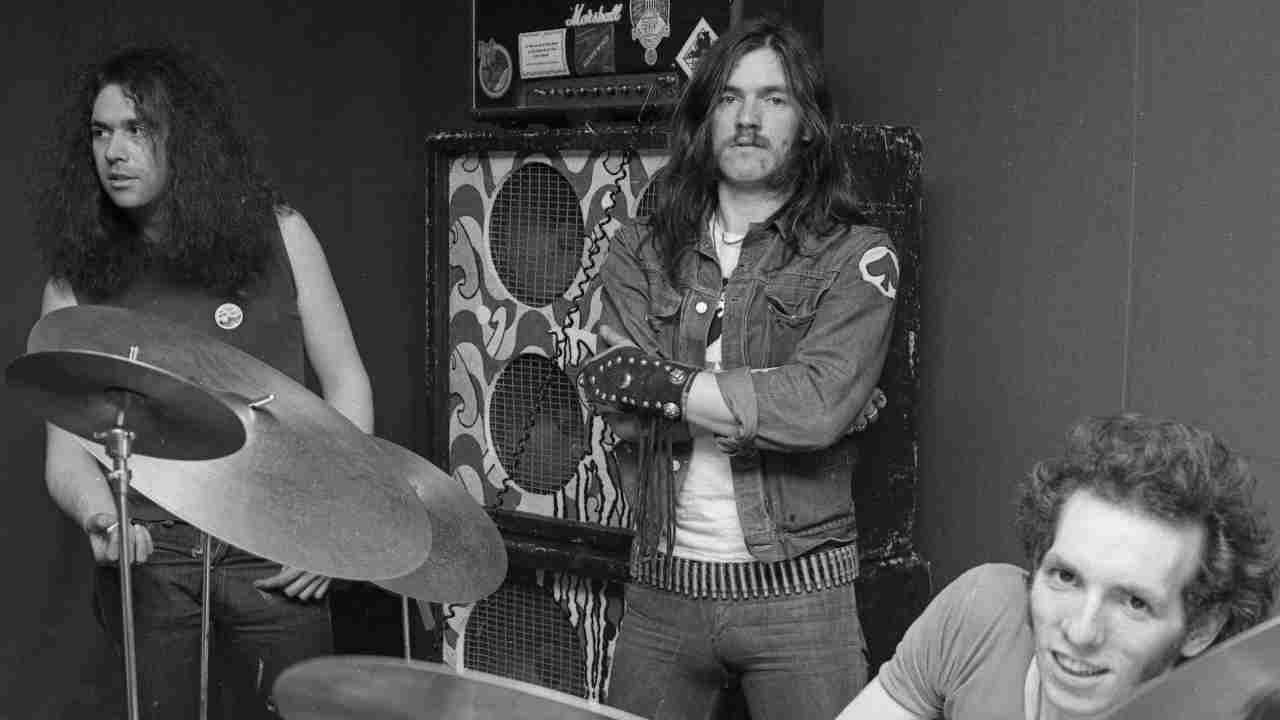

Originally featuring former Pink Fairies guitarist Larry Wallis and drummer Lucas Fox, the idea had been to bring in a second guitarist and a dedicated frontman-singer. “I was just gonna be the bass player,” Lemmy explains. “I wanted to get a singer in but, of course, we couldn’t find one. And it was cheaper for me to do it, cos I was already there.”

Making their live debut opening for Greenslade at London’s Roundhouse in July, Motörhead’s original line-up lasted just a few months before Fox was replaced by Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor, a former skinhead and Leeds United football hooligan, whose father had bought him a drum kit, saying, “If you wanna beat something up, beat this up.”

They had been recording tracks for what was supposed to be their first album, On Parole, but Wallis wasn’t cutting it and, besides, “Phil had a car and could give us a lift to the studio.”

Or as Taylor later recalled: “I met Lemmy through speed really. You know, dealing and scoring.” Joining Motörhead “just seemed like a good idea at the time”.

Still on the lookout for a second guitarist, Phil introduced them to Eddie Clarke, a bloke he’d met painting a houseboat. Fast Eddie, as he became known, was a part-time TV repairman who had played guitar for Curtis Knight.

“So we organised an audition and jammed all afternoon,” recalls Clarke, “and Lemmy and I found we had a lot of things like The Yardbirds in common. But Larry didn’t show up till the end, and when he did he wasn’t in very good humour. I didn’t hear anything for ages, then one Saturday afternoon there was a knock on the door and Lemmy was standing there. He gave me this fucking bullet belt and leather jacket and said, ‘You’re in.’ Larry had gone and I had my uniform!”

Thus the classic ‘three amigos’ line-up of Motörhead was born. There would still be further months of turmoil, though, before they were recognised as such. After Motörhead had cut their debut On Parole album for United Artists (Hawkwind’s label), the company rejected it (the album remained in the vaults until the band finally hit the Top 20 with Bomber in 1979).

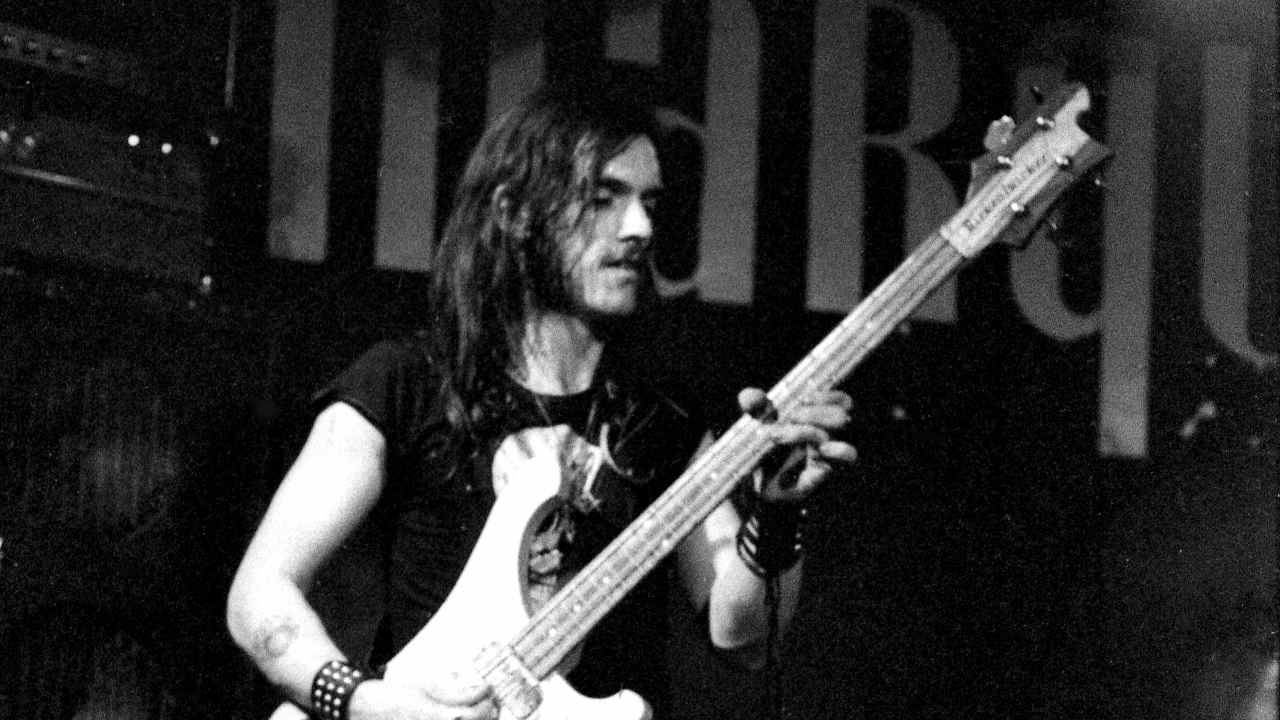

Instead, they recorded a single, White Line Fever, for Stiff Records (where old compadre Dave Robinson now was) – then suffered the indignity of seeing that shelved too. It seemed Motörhead’s poisoned-blood contusion of amphetamine-fuelled metal and furious, anti-everything punk energy was too much for the prevailing rock scene to handle.

“You had the punks on one side,” recalls Lemmy, “but we didn’t have short, spiky hair like them. And you had the hippies on the other, but we were just too fast and in-your-face for them, so no one knew what to think of us.”

Or if they did, they simply thought wrong. Reviewing one of their early gigs, Nick Kent of the NME described them as “the worst band in the world”. The band, though, had their own take on their emerging musical identity. “If we move in next door to you, your lawn will die,” Lemmy memorably told Sounds scribe Geoff Barton. And for a while it seemed like it might be true.

There was another attempt at an album – a largely re-recorded version of On Parole, retitled simply Motörhead, this time on the independent Chiswick label – in 1977, but yet again, the label were so freaked out at the results that they too had second thoughts before releasing it.

A patchwork collection of numbers based on the band’s live set and recorded at a time when, according to Lemmy, “we only had about three new original songs of our own”, the musical frock-coats of Hawkwind had been traded in for skin-tight leathers and the guitars now sounded like they were angry instead of trippy, the vocals positively spat out, Philthy’s rat-a-tat drums like machine-gun fire.

“It wasn’t exactly thought out, that record,” Lemmy shrugs now. “It was more like a demo, just bashing out the live set. We were more interested in the sound than the actual songs at that point, I think.”

Even once they had found a label prepared to release their records – Bronze, who issued the Louie Louie single – label boss Gerry Bron considered it “about the worst record I’d ever heard”. When it went straight into the Top 75, though, “I said, ‘Hang on a minute, this is a terrible record, but it’s gone into the chart without any kind of push at all,’ so I went to see them at Hammersmith Odeon and it was packed to the rafters with people going absolutely crazy. We had to sign them right away.”

Bronze had told them that if Louie Louie went Top 75, they could get the band on Top Of The Pops. Sure enough, Motörhead filmed their TV debut a week later. Clarke, who was doing a painting job on the night it was broadcast, “had to ask the punters if we could watch their telly, because I was on in a minute! I was standing there in my overalls with a paintbrush in my hand…”

As the guitarist now insists, the reason for the band’s early success was their very togetherness. Although there was tension, their bond was seemingly unbreakable.

“You hear a lot of good things and a lot of bad things about Lemmy, and most of them are true,” reflects Taylor. “He is a bastard, he does knock other people’s chicks off. But he’s also incredibly funny. Every time you go out with him, it’s a memorable experience.”

“We had a bond, and it went beyond whether you liked someone or not,” adds Clarke. “Me and Phil were especially close because Lemmy was a bit of a loner. [But] it never entered my mind whether I even liked Lemmy or not. We felt almost indestructible because we’d had so much shit thrown at us and we’d decided that no matter what happened, we were gonna fuckin’ carry on. The music business tried so hard to scupper us early on, and it made us dogged.

“Being in a band’s like being in a war – you don’t give a fuck whether or not a guy’s feet smell, you wanna know if he’ll keep you alive. That’s how Motörhead was.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Motörhead