South Africa’s post apartheid government has been toying with the idea of decriminalising sex work for almost two decades. But it has hesitated to act with the necessary courage to regulate the industry in a progressive way.

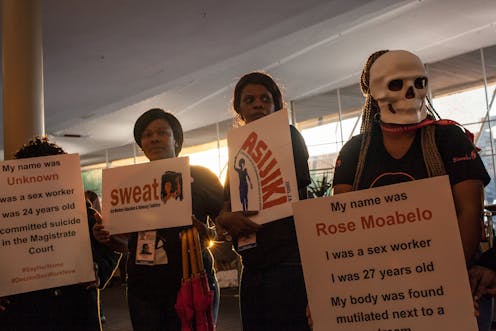

The reluctance to take bold action to decriminalise the sector has detrimental effects for sex workers. Decriminalisation would give sex workers access to labour rights and help prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. Most importantly, it would give sex workers more protection from violence. The recent discovery of the bodies of six women, believed to be those of murdered sex workers, in Johannesburg once again highlighted the dangers they face.

The incident has reignited the debate on decriminalisation.

Based on my research into the subject – including my 2006 PhD thesis – my view is that progress on this issue is hampered by the government’s fears of what might follow. The two biggest fears are that it will lead to a spike in the sex work industry and the possibility of child prostitution.

But these fears do not warrant inaction. Government needs to start drafting a legislative framework to regulate the industry and decriminalise sex work. This is the only way to protect sex workers from further abuse and violence.

Misplaced fear

Sex work is by no means a popular career choice. Decriminalisation is thus unlikely to cause an upsurge in sex work.

In the main, people are forced into sex work by socio-economic circumstances, including poverty, and a lack of alternatives.

Research indicates that 76% of sex workers in Cape Town entered the industry as a result of financial need.

In relation to fears about children, the country already has clear and separate statutory provisions in place to combat child prostitution. These include sections 15, 16 and 17 of the Sexual Offences Related Matters and Amendment Act 32 of 2007. Perhaps the most important of these is section 17, which specifically prohibits the sexual exploitation of children.

Read more: Murder of Johannesburg sex workers shows why South Africa must urgently decriminalise the trade

With these sections in place, the success of preventing an increase in child prostitution, once adult sex work was decriminalised, would depend on effective law enforcement.

A spike in child prostitution did take place in, for example, the Netherlands and parts of Australia, once they decriminalised the sex industry. Research shows that this was a result of ineffective law enforcement.

Exposure to violence

South Africa is a hotbed of crime and has one of the highest incidences of violence in the world.

Because of the illegal status of their work, sex workers are forced “underground”, which makes them more susceptible to violence than other citizens – who are already “at high risk”.

Research indicates that almost half (45%) of the South African sex workers who died in 2018 and 2019 were murdered. There are an estimated 167,000 sex workers in the country.

Sex workers are ideal targets of violence. Meeting clients in discreet places to hide their occupation leaves them exposed to violence from clients. They are also unlikely to report crimes against them if they fear being prosecuted themselves and abused further by the police.

The only way to stop violence against sex workers and protect their basic rights is to decriminalise sex work. The longer this reality is ignored, the more violence, including murders, will follow.

The history

Sex work in South Africa was originally criminalised in terms of section 20 (1A) of the apartheid-era Sexual Offences Act, 1957, which prohibits “unlawful carnal intercourse” or “acts of indecency” for reward. According to this statutory provision, the sex workers (mostly females) are the perpetrators of the crime, and their clients are accomplices.

Both the sex worker and the client are liable for prosecution and the same punishment, which includes imprisonment for a maximum period of three years with or without a maximum fine of R6,000 (US$325). But in criminal law terms, the conduct of a perpetrator (in this case the sex worker) is considered more blameworthy than that of the accomplice.

Read more: Sex workers in Nigeria deserve fair treatment from the media

A 2002 minority High Court judgment highlighted this distinction as indirect gender discrimination. The legislature then responded by introducing section 11 to the Sexual Offences Related Matters and Amendment Act 32 of 2007. The section provides that

A person (‘A’) who unlawfully and intentionally engages the services of a person 18 years or older (‘B’), for financial or other reward, favour or compensation to B or to a third person (‘C’)- (a) for the purpose of engaging in a sexual act with B, irrespective of whether the sexual act is committed or not; or (b) by committing a sexual act with B, is guilty of the offence of engaging the sexual services of a person 18 years or older.

This wording simply shifts the “more blameworthy” role of being a perpetrator to the client, while the sex worker becomes the accomplice. Although this removes gender discrimination and is more compliant with the constitution, it is not a progressive step in the direction of decriminalisation.

Both the sex worker and client are still liable for prosecution and punishment and are forced to operate underground.

The South African Law Reform Commission first reviewed the law banning sex work in 2006. It opted to continue with the approach of criminalising the sex industry.

Discussions continued in 2009 and again in 2017. But nothing came of them. The opportunity to make changes was missed again recently when the Sexual Offences and Related Matters Amendment Act failed to decriminalise sex work.

Looking forward

Fearing what might follow decriminalisation does not justify continuing to criminalise sex work. It is here to stay, whether legal or illegal.

Criminalisation has been shown to be ineffective in eliminating sex work.

In addition, it’s been shown that it forces it underground, exposing sex workers to violence, including murder.

It’s time South Africa took more progressive steps.

Decriminalisation will come with its own challenges and teething problems, but continuing to turn a blind eye to the plight of sex workers will mean that they live in danger.

Read more: Unequal power relations driven by poverty fuel sexual violence in Lake Chad region

The government can learn valuable lessons from other countries, such as New Zealand, were sex workers are regulated by law.

They enjoy better protection against violence, have labour rights, can decline clients and have access to healthcare. Brothels are only allowed to operate in certain areas and child prostitution remains a crime.

Rinda Botha does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.