It’s easy to assume protected areas such as national parks conserve wildlife – that seems obvious. But what is the proof? And how does park success vary across different ecosystems – in deserts versus tropical rainforests, or wetlands versus oceans?

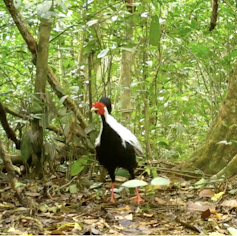

While we can use satellite imagery to measure the effect of protected areas in reducing human impacts such as logging, you can’t see the animals from space. In particularly dense tropical rainforests, it was nearly impossible to accurately monitor wildlife, until remotely triggered camera traps became available in the past decade.

There is a longstanding conservation debate on the benefits that protected areas such as national parks have for biodiversity.

Some scientists have argued that conservation success inside park boundaries may come at the expense of neighbouring unprotected habitats. Essentially, they suggest parks displace impacts such as hunting and logging to other nearby areas. The technical term for this is leakage.

On the other hand, marine parks have often reported higher biodiversity nearby. Fish reproduce successfully inside park boundaries and their offspring disperse, benefiting surrounding habitats in a “spillover” effect.

We set out to see which of those effects actually prevails in protected land areas and their surrounds. Our new study, published today in Nature, shows parks do enhance bird diversity inside their borders. Large parks also support higher diversity of both birds and mammals in nearby unprotected areas.

Read more: The new major players in conservation? NGOs thrive while national parks struggle

What did the study look at?

We recruited an international team of scientists to conduct a comprehensive analysis of bird and mammal diversity inside and outside parks across South-East Asia. We used more than 2,000 cameras and bird surveys across the region.

South-East Asia is one of the most biodiverse regions on Earth, but hunting is a key concern. It’s a prime suspect for why diversity has often been assumed to decline outside protected park areas.

Hunters are mobile, so hunting bans within park boundaries may only displace these activities to nearby unprotected areas, undermining their net benefit. To be honest, we were surprised mammal diversity was higher outside large parks. It’s common to see hunters both inside and outside parks in many countries.

We expected hunters’ removal of game animals would reduce diversity outside parks. However, it appears large parks limit the impacts of hunting so it does not completely remove these animals. Specifically, when comparing unprotected areas near large reserves to unprotected areas that didn’t border large reserves, we found large reserves boosted mammal diversity in unprotected areas by up to 194%.

However, a sad note from our study was the finding that only larger parks significantly enhanced mammal diversity, casting doubt on the effectiveness of smaller parks for mammal conservation. Recent work in the region suggests many large mammals persist in small parks, but our study shows the presence of a few resilient animals in small parks doesn’t scale up to higher biodiversity overall.

Read more: In protecting land for wildlife, size matters – here's what it takes to conserve very large areas

Not all parks are equal

These findings are especially timely for the United Nations, which recently announced more ambitious biodiversity targets, including significant expansions of global protected areas. The UN strategy is to conserve 30% of Earth’s lands and waters by 2030 – the so-called “30 by 30 goal”. Massive expansions of the global area of protected land will be difficult and expensive, but our results support this approach.

The work provides a clear case for park design to consider size. Larger parks routinely had higher bird diversity. Large mammals such as tigers and elephants travel huge distances and don’t see park boundaries drawn on maps. Larger parks support these wide-ranging animals that move across entire landscapes.

Considering the UN’s goal of increasing protected area to 30% of the world’s surface, our findings support the creation of fewer larger parks, rather than many smaller ones.

Read more: Protecting 30% of Australia's land and sea by 2030 sounds great – but it's not what it seems

Next steps in South-East Asia and Australia

Our findings also provide a much-needed conservation “win” for South-East Asia. Despite being a biodiversity hotspot, the region suffers from high rates of forest loss and hunting, which pose threats to birds and mammals.

Our team built a collaborative network and massive database to conduct the analysis, and this can also be used to answer other questions. Our next project will quantify shifts in abundance – the numbers of animals rather than numbers of species – inside and outside parks. We suspect parks will support increased mammal and bird abundances, even more than increased in wildlife diversity.

Based on the success of the Asian collaborative network project, a related team is now building a domestic collaborative network and database to conduct similar analyses, called Wildlife Observatory of Australia. Key questions will include the impact of fire and climate change on Australia’s wildlife diversity and abundance.

The research discussed in this article was supported by the United Nations Development Programme, NASA grants NNL15AA03C and 80NSSC21K0189, the National Geographic Society’s Committee for the Research and Exploration award #9384–13, the Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award DECRA #DE210101440, the Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, Nanyang Technological University Singapore, the Darwin Initiative, Liebniz-IZW, and the Universities of Aberdeen, British Columbia, Montana and Queensland. Mammal data collection in one study area (out of 65) was funded by Sarawak Energy Berhad; no personnel from that agency participated in the data collection or analysis or reviewed the manuscript before it was submitted.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.