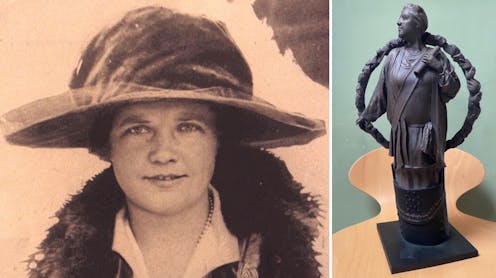

The design for a statue of a leading suffragette has been unveiled in Newport, south Wales. Margaret Haig Thomas or Lady Rhondda was a lifelong campaigner for women’s rights and was the first woman to hold a hereditary peerage, though she was barred from taking up her seat in the House of Lords. She was also a successful businesswoman at a time when married women were often excluded from gainful employment.

The statue by artist Jane Robbins is part of a wider campaign dedicated to marking the contribution of women to the history of Wales. The sculpture is expected to be cast in bronze and erected in Newport in 2024.

The relationship between statues and our understanding of history is complex. In 2020, the toppling of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston sparked important questions about what statues are for and how they contribute to the public’s understanding of the past.

Many statues, like Colston’s, were created in the 19th century as honorific symbols of power. Those representations of authority are now rightfully being questioned. Conversely, the creation of statues of women has the potential to acknowledge their often hidden yet important impact.

Across the UK, there are very few statues dedicated to named women that aren’t royal or mythological in nature. Out of more than 800 statues, only 128 are of named, non-royal women. Until late 2021, there was not a single such statue in Wales.

This is why the ongoing campaign to create a statue of Lady Rhondda matters. She was a woman who sat on the boards of 33 companies and became the first female president of the Institute of Directors in 1926. She was an outlier.

But looking only to Lady Rhondda’s professional success risks aligning her with those traditional forms of biography, memorials and statues that typically celebrate “great” men as exceptional individuals.

Very few women can fit into this mould. And this limited view of success may be one of the reasons we know so little about women’s influence throughout history. Fortunately, the work of historians has uncovered Lady Rhondda’s life story beyond her professional achievements.

Lady Rhondda was an active member of the militant wing of the suffragettes, the Women’s Social and Political Union, under Emmeline Pankhurst and was arrested for setting fire to a postbox. She travelled across Wales mobilising women (and a few men) to the cause.

One of her vital accomplishments was her push for further reform immediately after landmark changes to women’s rights in the early 20th century. In fact, she shattered the misguided notion that votes for women meant equality had been achieved.

When the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 permitted women to become professionals, such as solicitors, magistrates and civil servants, for the first time, it appeared that Lady Rhondda could also take up her hereditary peerage and sit in the House of Lords. But her entry was blocked by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Birkenhead.

Though she lost her case challenging this and was never able to sit in the Lords, she spent the next few decades campaigning for reform until her death in 1958. Her efforts influenced the passing of the Peerage Act 1963, which enabled female hereditary peers to take their seats for the first time.

Lady Rhondda mobilised women to push for change on other fronts too. In February 1921, she established the Six Point Group. This was a pressure group comprising women able to vote at that time to work towards equal rights through legal reform. As their name suggests, they targeted six issues at a time. Once they had achieved as much as they could in one area, another issue would take its place.

The activities of the Six Point Group were publicised in Time and Tide, a groundbreaking feminist periodical that Lady Rhondda founded, owned and edited. It included work by literary greats such as Virginia Woolf and George Bernard Shaw.

While the Six Point Group remains a relatively unknown part of the women’s movement, it asserted an important influence. It raised awareness of issues relating to equal pay, reform of the law on child assault and the rights of housewives. It was also behind the establishment of the Married Women’s Association, which I have argued had a profound influence on married women’s property rights throughout the 20th century.

Statue

The campaign for a Lady Rhondda statue was initiated by Monumental Welsh Women, an organisation seeking to correct the almost complete absence of statues representing women’s achievements throughout history. Efforts to fund the statue continue.

In contrast with traditional statues, Lady Rhondda’s will be just over 2 metres (7 ft) in height, so the public can observe its features up close. The statue’s hoop will be made from hand casts of the women involved with the project, symbolising unity.

If it is erected, the statue will create new opportunities for dialogue not just about why women should be commemorated, but how.

Sharon Thompson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.