Lightning strikes across Earth could make ultrahot "killer electrons" rain down around our planet, according to new research from scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder. Due to this result, the team suggests that space weather and Earth can unite to play "cosmic pinball."

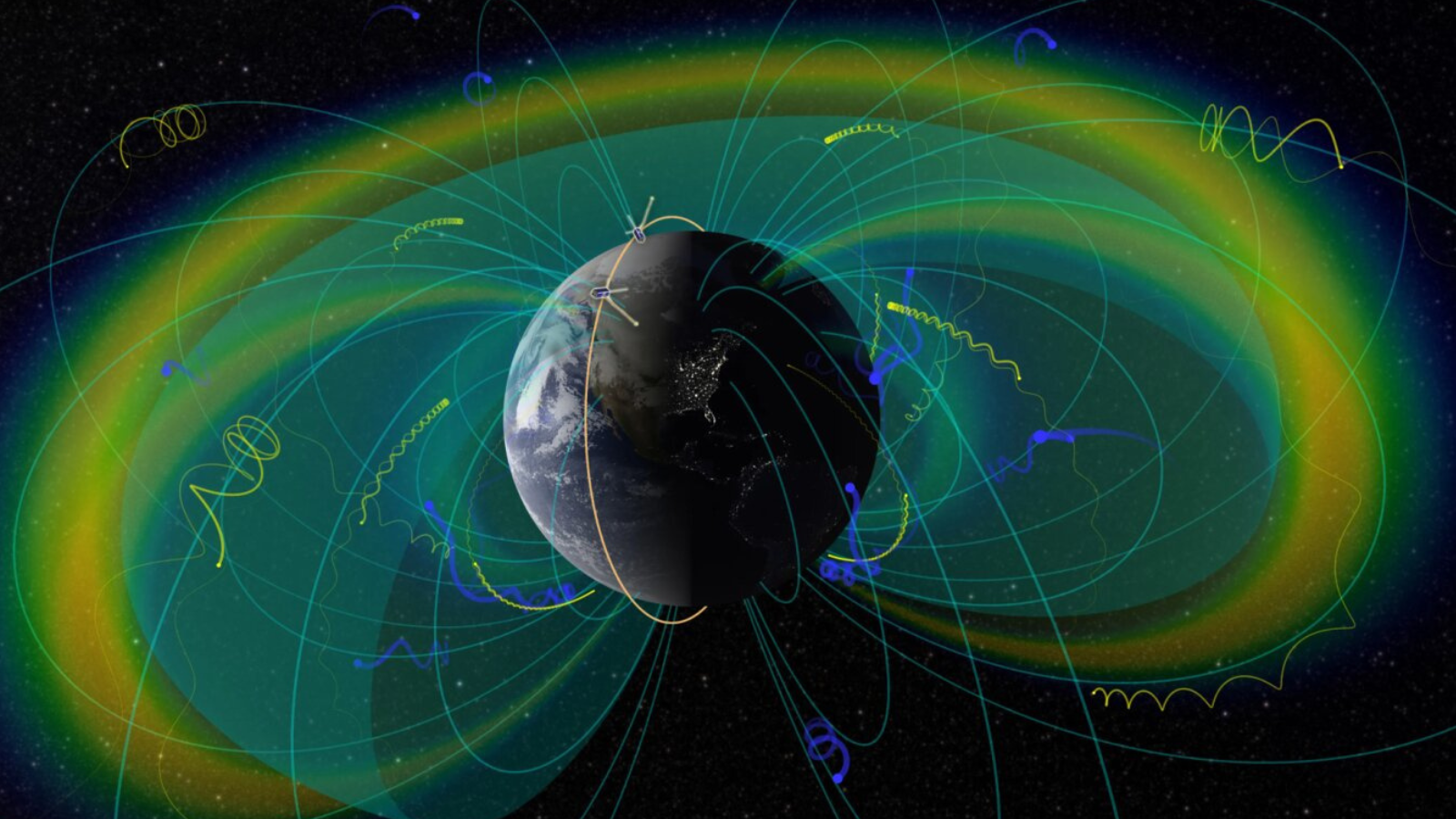

The discovery was made almost by chance while the team was studying satellite data that showed high-energy and high-speed "hot" electrons could be dislodged from the inner radiation belt — a region of charged particles wrapped around our planet that's held in place by Earth's protective magnetic bubble, known as the magnetosphere.

This research could help scientists protect satellites and other instruments in orbit from damage, and assist in protecting astronauts from potentially lethal radiation on future space missions. It also suggests that space weather and Earth weather are more intertwined than previously suspected.

"These particles are the scary ones or what some people call 'killer electrons.' They can penetrate metal on satellites, hit circuit boards, and can be carcinogenic if they hit a person in space," team leader and University of Colorado Boulder researcher Max Feinland said in a statement.

Related: SpaceX's Polaris Dawn astronauts will make a daring trek into Earth's Van Allen radiation belt

Killer electrons charge!

Wrapped around Earth are two belts of trapped high-energy particles, held in place by the magnetosphere. These are known as the Van Allen radiation belts.

Killer electrons race through these belts at nearly the speed of light, carrying with them a great deal of energy. Not only can these particles penetrate satellite shielding, but they can also cause microscopic lightning strikes that can damage — or even destroy — vital and delicate spacecraft components.

The inner region of the belts is considered to begin at an altitude of around 600 miles (966 kilometers) over Earth, while the outer layer is thought to start at around 12,000 miles (19,312 km) over our planet's surface.

The Van Allen belts serve as a loose barrier between Earth's atmosphere and its space environment. They are also dynamic, capable of moving and changing. Scientists have known for some time that charged particles can fall from the outer radiation belt toward Earth. Low-energy, or "cold," particles have also been detected falling from the more stable inner radiation belt.

This is the first hint that high-energy charged particles can also "rain" from the inner belt, which had been considered more stable. It's also the first hint that this "electron rain" can be triggered by lightning.

"Space weather is really driven both from above and below," team member Lauren Blum of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder said in the statement. "Typically, the inner belt is thought to be kind of boring. It's stable. It's always there."

The team theorizes that when lightning flashes in the sky over Earth, radio waves are launched toward space. If these radio waves hit electrons in the radiation belts around our planet, they can shake loose electrons, causing "lightning-induced electron precipitation" or "electron rain."

While analyzing data from NASA's now-decommissioned Solar, Anomalous, and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer (SAMPEX) satellite, Feinland saw "clumps" of high-energy electrons moving through Earth's inner radiation belt. He took these observations to Blum, who told him: "That's not where these are supposed to be."

Cosmic pinball

Investigating this further, the duo identified 45 surges of high-energy electrons in the inner radiation belts occurring in the decade between 1996 and 2006. Feinland then compared this data to records of lightning strikes over North America. What emerged was a correlation between lightning strikes and peaks in electrons, which occurred around a second after lightning struck the ground.

The team thinks that when lightning strikes, it begins a frantic game of pinball that encompasses the entire Earth. Triggered radio waves ripple upward into space, striking electrons in the inner radiation belt.

This acts like an "add ball" feature in this figurative pinball game, dropping electrons that then chaotically bounce between the northern and southern hemispheres of Earth. This phase of the process lasts just 0.2 seconds. Some of the electrons frantically shuttling between our planet's northern and southern hemispheres then drop into our atmosphere.

"You have a big blob of electrons that bounces and then returns and bounces again," Blum said. "You'll see this initial signal, and it will decay away."

Blum, Feinland, and colleagues don't currently know how often these bouts of "killer electron rains" occur. One theory is that they are most common during periods when the sun is especially active and blasts more high-energy electrons at Earth to be grabbed by the magnetosphere and replenish the Van Allen belts.

The team's research was published on October 8 in the journal Nature Communications.