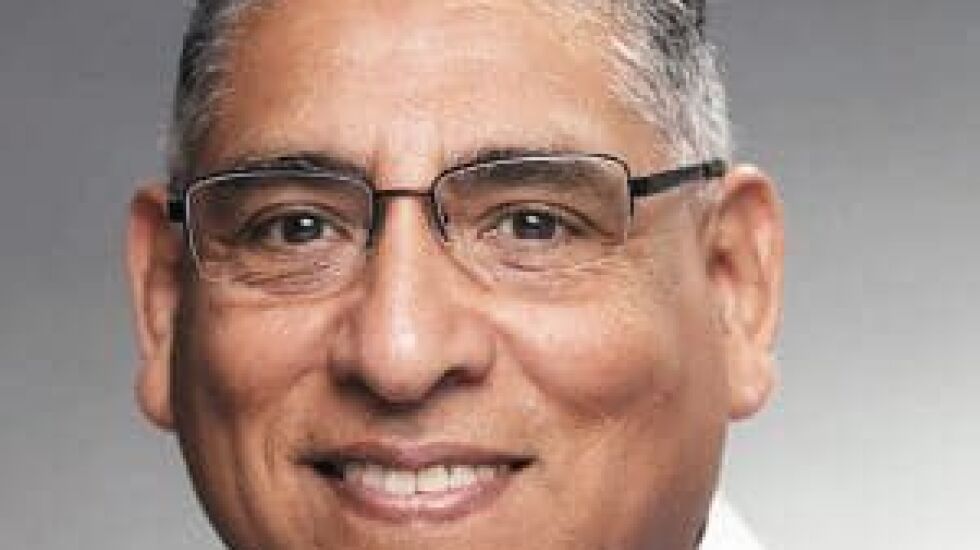

The Rev. Luis Andrade, who had served congregations in Elgin and Burr Ridge, was expelled from the Episcopal Church as a priest in 2019 after an internal investigation found that accusations of sexual misconduct three women leveled against him were credible.

In a lawsuit filed in Cook County, one of the women accused Andrade of raping her when they were at a religious conference at a North Carolina retreat center in 2016.

Another — an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who had attended both of his Chicago-area Episcopal parishes, the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer in Elgin and St. Helena’s Episcopal Church in Burr Ridge — says he “manipulated” her into having sex, then told her that immigration authorities might find her if she told anyone.

The third woman also accused Andrade of inappropriate sexual encounters. That woman — who says she was married and a member of one of Andrade’s parishes and also an undocumented immigrant from Mexico — says they sometimes occurred at the church and after Andrade counseled her about marital problems.

Andrade, 49, never was charged with any crime and denies all of the accusations.

He recently moved on to be a priest in a small denomination that describes itself as independent Catholic — the fourth faith group he has served as a clergy member. During a recent Spanish-language ceremony at his church in Berwyn, called Parroquia La Misericordia, he was installed as a bishop in the Apostolic Catholic Church of the United States — a denomination that, although it isn’t affiliated with the Roman Catholic church, maintains many of its rituals but allows its clergy to marry.

In interviews at his Cicero home, Andrade says in response to the three women’s accusations that the only thing he has done wrong was being “unfaithful” to his wife.

The Episcopal church disagrees.

“The church believes these women,” says Jim Naughton, a spokesman for the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago.

It paid financial settlements with all three women: $75,000 to the woman who sued, $60,000 and $50,000 to the other two — and expelled Andrade from the priesthood for “conduct unbecoming a member of the clergy,” according to Naughton. He says the sexual misconduct accusations were the basis for Andrade’s expulsion.

Andrade says his congregation, which meets at a Lutheran church, includes about 30 families, though more than 150 people attended his recent ordination.

Andrade says the Episcopal church mishandled its investigation of the complaints against him and shouldn’t have removed him from the priesthood.

Bishop Jeffrey Lee, who was the top Episcopal cleric in Chicago at the time and signed Andrade’s expulsion order, stands by that action.

“The Diocese of Chicago took appropriate action in removing Luis Andrade from the priesthood,” Lee says. “If he were still a member of the Episcopal church, he would not be exercising any kind of ordained ministry.”

A move to the U.S., a new denomination

Andrade is from Ecuador, where he was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 2000 and assigned for a time at a school, according to records and interviews.

He says he visited Africa as a missionary in 2004, then moved later that year to the United States, serving briefly as a Roman Catholic priest in the Chicago area, officiating at Mass on a fill-in basis for vacationing clerics.

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago didn’t respond to questions about Andrade.

He says he decided to leave the Roman Catholic priesthood and got married in 2005.

His wife was born in the United States but raised in Ecuador, he says, and their families knew each other.

He became an Episcopalian in 2009 and the following year began the process to become an Episcopal priest, being ordained in 2012, Naughton says.

Andrade served for a time at the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer and then at St. Helena’s Episcopal Church.

According to Naughton, the diocese performed a background check that included contact with the Archdiocese of Quito, Ecuador, and turned up no problems.

Andrade joined the Episcopalian clergy at a time the church was pushing to serve and draw more Hispanics. An NPR report in 2012 noted that “Latinos are the fastest-growing ethnic group in the United States, but only 5% of all Hispanics attend a mainline Protestant church . . . . For the Episcopal church, those numbers are an opportunity,” with the denomination engaged in “strategies to reach Latinos.”

Young and charismatic, Andrade attracted parishioners and drew notice within the 1.5 million-member national church, led then, as now, by presiding Bishop Michael Curry. A religious conference in Dallas in 2016 had Curry as its keynoter and Andrade among other scheduled speakers.

‘I cried in silence as he raped me’

The woman who accused Andrade of rape says she met him in June 2016 at a Latino ministry conference in Virginia, where she was living. She says they became friends. In an interview, she says that, although there was nothing physical between them, they flirted and exchanged what she describes as inappropriate texts over the next few months.

The woman — who asked that she not be identified by name — says she was married at the time to an Episcopal priest but was having problems and eventually divorced.

At an Episcopal conference in August 2016 at a church-run retreat center in Hendersonville, North Carolina, she says Andrade was in the lobby when she arrived and, without her asking, took her luggage and walked her to a rustic cabin where she’d be staying.

Once inside, she later told the Henderson County, North Carolina, sheriff’s office, “I heard the deadbolt lock. As I turned around . . . he was already on me.” She told investigators Andrade grabbed her by the back of the head and “forcefully” kissed her.

“I couldn’t escape,” she said, according to police records. “I kept saying, ‘No! Please don’t!’ He didn’t stop, and I swallowed the gum I was chewing.

“I cried in silence as he raped me.”

The woman says that in the weeks that followed, “I was in severe mental breakdown.” Her husband “was out of the country,” she says. “I was alone, it was very confusing for me.”

In November 2016, she says she decided to file a complaint against Andrade with the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago, which suspended him from public ministry and began investigating.

Initially, the woman says, she cooperated with the investigation, communicating with church leaders and accepting counseling sessions.

Some church leaders were supportive, she says, including the bishop in her home diocese in Virginia, who called Lee, his counterpart in Chicago, to tell him about his parishioner’s accusations.

Naughton says the Chicago diocese quickly put out word in English and Spanish to St. Helena’s congregants to come forward if they had any pertinent information. When no one came forward, Naughton says, they asked Andrade which women he’d been counseling and contacted them.

The woman who accused the priest says a woman in the congregation contacted her with names she passed on to the diocese.

In 2017, the woman filed a separate complaint with the church, saying the Rev. Anthony Guillen, who oversees Latino ministries under Curry, was dismissive about her accusations and wasn’t taking seriously other instances of inappropriate conduct by clergy. She described drinking and lewd conduct by clergy members at Latino church conferences after hours.

Curry’s spokeswoman Amanda Skofstad says: “When we were made aware of concerns within Latino ministries, these concerns were taken seriously and investigated. All parties involved received anti-harassment training as well as training in gender norms and cultural differences.”

Guillen “was professionally assessed, underwent intensive training and other services, was reevaluated after and was determined by an external expert as fit to continue in his ministry,” Skofstad says.

Says Curry: “The Episcopal church has worked hard to prevent and address sexual abuse and sexual harassment and will continue to strengthen our policies.”

The woman who’d complained to the diocese says she suffered mental trauma that led to hospital stays in 2017 and 2018 and that she became increasingly disenchanted at the Chicago diocese’s handling of its Andrade investigation.

At that point, he hadn’t been defrocked — deposed in Episcopal parlance. And the woman says church officials weren’t being forthcoming with her about their investigation. She says she thought they were stalling.

Naughton says that wasn’t the case.

“Bishop Lee didn’t depose Andrade immediately because he wanted to keep some authority over him,” the diocese spokesman says. “Had he deposed him right away, he could not have compelled him to go into inpatient therapy . . . . He did, however, remove him immediately from ministry, and Andrade never returned to ministry in the Episcopal church.”

The woman says she hadn’t filed a police report by that time because she believed the church investigation would be adequate.

Though the diocese didn’t call police either, Naughton says, “There was absolutely no attempt on our part to keep this quiet. The diocese didn’t report . . . to the police because that would have been the role of the diocese to which she first reported the abuse — the Diocese of Southern Virginia.”

Nor did Episcopal church officials report the other two women’s later complaints to the police about Andrade.

“The diocese didn’t report Andrade’s abuse of the women in the congregation to the police because none of the women involved wanted us to do so,” Naughton says. “At least one of the women had immigration issues in her family and was extremely concerned that law enforcement not be involved. We offered repeatedly to support them if they did file charges, but they declined. Two of the victims, as you know, received their settlements anonymously, and we continue to protect their anonymity.”

Encouraged by friends, the first woman filed a police report in 2018 with the Henderson County sheriff’s office but says a detective assigned to the case appeared to do little.

A sheriff’s spokesman says the case “had been assigned to a detective, and then that detective left our agency.”

In 2019, when the woman “contacted our agency to inquire about the status of her case, at that point a detective spoke with her and followed up on the case,” the sheriff’s spokesman says. “After speaking with her, the detective gathered all the previous reported information along with the information he obtained during the telephone call with her and met with the district attorney, who, after reviewing the case, declined prosecution. The exact reason for his decision to not to prosecute is not known but probably took into account that there was no physical evidence and no witnesses to the alleged incident.”

In 2019, more than two years after she filed her complaint with the Episcopal diocese, the woman says she was tired of what she regarded as inaction by the church and sued the diocese, Andrade and Lee in Cook County circuit court.

In addition to accusing Andrade in the civil case of “harmful and offensive touching of a sexual nature, kissing, groping and rape,” the suit says the priest “commenced a pattern and practice of abuse that subjected women he victimized to sexually offensive and abusive conduct that was entirely unacceptable, unsolicited and unwanted and that no woman, wife, mother or daughter should have been forced to endure.”

The lawsuit says the diocese knew or should have known Andrade used his role as an Episcopal priest to “groom” women.

While settlement talks were underway, the woman says, diocese officials accused her of having had an “affair” with Andrade, questioned her truthfulness and asked her whether she really wanted to destroy his ministry and marriage.

“They attacked my dignity,” she says.

The church initially offered her $13,000 to settle the case but later agreed to $75,000, she says.

‘They destroyed me’

Andrade portrays what happened with the woman as “an affair” that was morally wrong since he was married but consensual. He says his reputation and career were put in jeopardy because he broke things off with the woman and that she has a vendetta against him.

The woman says that’s not true.

Andrade acknowledges having had sexual encounters with other women but says none involved “registered” church members or women he’d counseled and that any sexual activity didn’t happen on church property.

One of the women from Mexico tells a different story. She says she met Andrade at Redeemer, the Elgin church she attended and where he served and that he got close to her family while her daughter was hospitalized in a coma.

The woman, who lives in the northwest suburbs and agreed to speak as long as she wasn’t named, says her daughter recovered. And then, she says, Andrade encouraged her to follow him to his new assignment in Burr Ridge at St. Helena’s, saying she could repay God for having helped her daughter by helping Andrade build his new congregation.

The woman says she volunteered to clean the church, attended services and helped plan fundraisers. She says she confided in Andrade she was having marital problems and that he complimented her on her work and made her feel valued but also started to touch her inappropriately in his office.

“I told him that he’s a priest, and he told me that he was a man, too, and had necessities,” the woman says, speaking in Spanish.

She says he told her to meet her at a suburban hotel for a church meeting and that, when she got there, they were alone and that he started playing videos showing how to do a massage.

She says she felt scared and that Andrade “manipulated” her into having sex.

She says that, after that, she avoided the church for two months but returned after Andrade called and said her husband would get suspicious if she didn’t go back.

She says she and Andrade then had other sexual encounters — inside St. Helena’s and elsewhere.

The woman says she warned other women at church about Andrade.

She says that, when the church investigation began after the complaint from the woman who later sued, Andrade called her regularly and said immigration authorities could find out she was undocumented if she talked to church officials or the police.

She says she told the diocese about Andrade anyway and that she and her children began receiving harassing messages and calls from parishioners telling her she was destroying his life by coming forward.

“Psychologically, they destroyed me,” she says. “That’s when I decided to take some pills and commit suicide.”

She says she was hospitalized for about a week, then too scared to go home after that, lived for a time out of her car or stayed with friends.

She says much of the settlement money she got from the church went toward medical bills and that she still has panic attacks and trouble sleeping and takes medication for depression.

“I have a lot of sadness in my heart,” she says. “My life changed a lot. My son hates me, and I think it’s because of all of this. My husband tells me he’s with me out of pity. The people at the church let me know that I’m nothing because they still blame me in my community. I don’t live in peace.”

The other woman from Mexico told a similar story, saying she started attending weekly services at St. Helena’s after a friend suggested it could help as she worked through problems in her marriage. She felt a sense of tranquility there and she soon was spending time during the week volunteering at the church.

That’s how she started opening up to Andrade about her marriage problems. He suggested she sign up for counseling sessions with him, she says.

Once while at the church, Andrade kissed her, she says.

Andrade later had sex with the woman twice after counseling sessions — once inside his church office and another time at his home, the woman says. She remembers having sex with Andrade at least one other time on church property.

“Looking back, I feel that based on everything I told him about what I was going through, what I told him about what my husband had done — he didn’t force me, but, after, I asked myself why did I do it,” she says. “Perhaps I felt vulnerable because of what I was going through.”

‘He never told me’

After the Episcopal church booted Andrade, he joined the National Catholic Apostolic Church in the United States, a small denomination led by Michel Pugin, a former Roman Catholic monk in the Benedictine religious order.

When Lee learned of this in 2020, he wrote Pugin “to inform you that on October 15, 2019, I issued an order in accordance with the canons of the Episcopal church removing Luis Andrade from the priesthood.

“As of that date, Mr. Andrade is no longer permitted to function as an Episcopal priest. This was an action taken following a canonical disciplinary process that began in November 2016 and the order, called an order of deposition, is permanent.”

Pugin wrote Lee back: “Father Luis has been very honest with us about his journey with your diocese. The decision in accepting him in the ranks of our clergy is due to his honesty and life experience. We are all sinners and all need to be forgiven as Christ forgave if we are truly repentant.

“I hope and pray that this letter you sent us was not simply to belittle Padre Luis Andrade, but to just inform us that he is not a priest of your diocese,” Pugin wrote.

Reached by phone recently while in Haiti on a mission trip, Pugin says of Andrade: “I knew about the scandal of the affair. He was upfront with us.”

Asked whether he knew Andrade had been accused of raping one woman and coercing two others into having sex, Pugin says, “Oh, my God, he never told me.”

Andrade says that he did tell Pugin about all of the accusations he faced.

Pugin says he heard of no problems with Andrade during his time with his denomination, which Andrade abruptly left earlier this year while serving as its chancellor, the No. 2 cleric.

Two Sundays ago, Andrade was formally installed as bishop in another small denomination, the Apostolic Catholic Church of the United States.

Jose Villegas, the denomination’s leader, officiated at the service, which included Andrade laying prostrate on the altar for a time.

Andrade says he has expansion plans for his faith group.

Elvia Malagón’s reporting on social justice and income inequality is made possible by a grant from The Chicago Community Trust.