Kenya’s former president Mwai Kibaki, who died last week, was widely praised for his economic transformation of Kenya, first as finance minister from 1969 to 1982 and then as the third president of Kenya from 2002 to 2013.

But Kibaki also left an enduring legacy on Kenya’s education sector.

Kibaki left his mark on education in two areas: the widening of access to education and the embrace of a business-style model for universities.

When Kibaki came to office, there was an education access crisis in both basic and higher education.

Numerous charges introduced by schools (such as building funds and activity fees) had increased the cost of education for the poor. Primary school enrolment was around 86% but, in 2002, the transition rate, from primary to secondary school stood at just 46%.

The growing demand for university education, due to population growth, limited access to only those who had performed exceptionally well in secondary education. Furthermore, university governance and operations had been constrained by political interference by the political class.

Kibaki’s goals were to expand access both in primary and university education, and to make universities more efficient and self-sustaining by reforming management and commercialising them.

These contributions, though positive, also had their drawbacks.

Free primary education

When he took office as president in 2003, Kibaki launched the widely praised Free Primary Education programme. Under it, all fees in primary schools were abolished. This wasn’t the first time this had happened. Primary school fees were first abolished in 1978 but, due to declining state support, schools introduced a myriad of non-tuition fees. This defeated the goal of free primary education.

Kibaki’s government strategy allocated each public school grants based on student enrolment. This allowed them to buy textbooks and meet other operational costs. This meant increasing the education budget from 12.4% of the national budget in 2004 to 17.4% in 2005.

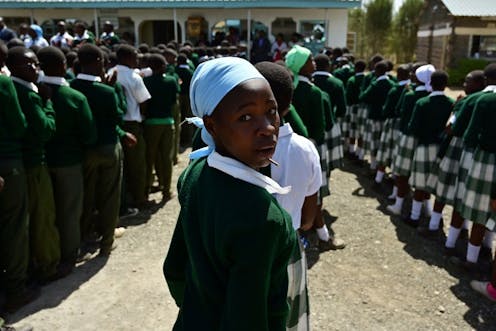

The Free Primary Education programme enabled millions of poor children to enroll in school. It is estimated that primary school enrolment rose from 6 million in 2000 to 7.4 million in 2004.

Free Primary Education was, and continues to be, a noble program that addresses equality in primary education access. Nevertheless, its implementation had disastrous consequences for equity and quality in education.

No extra classrooms were built nor additional teachers hired. This resulted in overcrowded classrooms with overworked teachers. Indeed, the teacher-student ratio increased from one teacher to 40 students, to one teacher for 60 students. The deterioration of quality of public schools became evident and poor performance in national exams proved this.

Those that could afford it, removed their children from well-performing public schools and enrolled them in expensive private academies. It is during Kibaki’s regime that the country saw the rise of high-cost private schools populated by scions of the middle and upper class. Indeed, enrolment in private academies almost tripled between 2005 to 2009 from 4.4% to 10.5%.

I also believe it nurtured an education entrepreneurial class whose interest in education was merely profit rather than the overall education of the child.

Equally troubling for Free Private Education programme was the weak financial oversight that resulted in massive theft of public funds. While some reports in 2009 indicated that Ksh.178 million (US$1.54 million) of the program’s funds were squandered by senior education officials and headteachers, other reports estimate that billions could have been stolen.

Upon his election in 2002, president Kibaki had declared corruption would cease to be a way of life in his government. However Kibaki’s vaunted anti-graft campaign found its waterloo in his pet education project.

Commercialisation of universities

Kibaki’s reform footprints in education are also still evident the university sector. Kibaki’s presidential term saw the greatest expansion of public university education in the country. When he took office, Kenya had only six public universities. When he left in 2013 the number had grown to 22. Most of the 17 (77%) public universities were established in one year, between 2012-2013.

Student enrolment grew from 71,832 in 2003 to 195,428 in 2013. Kibaki valued access to quality higher education as the key drive to economic growth. He argued that Kenya’s university education should be benchmarked against global standards and market needs.

Kibaki’s ultimate aim for universities was that they raise their own revenue and be less dependent on government. Hitherto, public universities depended on state funding for development, maintenance and operations supplemented by a modest state-regulated student tuition fees.

To do this, he commercialised universities and set about infusing them with corporate-style governance structures. He depoliticised the chancellorship by appointing corporate leaders and scholars as public university chancellors. This was a dramatic break from the past. His predecessor, Daniel arap Moi, was the chancellor of all the public universities.

In this new leadership structure, Kibaki expected policies and decisions in the universities be driven by financial and academic considerations rather than political calculations. This meant universities also had to plan for resources that would come from elsewhere, rather than the exchequer.

It is policy that saw public universities launch a range of initiatives in a bid to commercialise their operations. Ventures included:

academic programmes that included parallel programs, that is, admission of additional self-sponsored students who paid higher tuition fees beyond the normal government-funded students

the creation of mortuaries: medical schools in universities started offering body mortuary services to the public at a fee

establishment of branch campuses to admit more fee-paying self-sponsored students beyond the immediate location of the main university

But Kibaki’s vision of vibrant well-resourced public universities raising additional revenues to supplement government grants failed to materialise.

Today, many public universities are on the brink of financial insolvency with debts to the tune of Ksh10 billion (US$87 million). Many are unable to meet basic operating expenses.

But these university reforms had unintended consequences. Their extensive commercialisation of universities and expanded access resulted in decline in quality of learning, a challenge that still haunts the universities today.

In 2016, the government had to reverse course and outlaw branch campuses and parallel programs to stem the tide of quality decline.

Significantly, Kibaki’s expansion of public universities was in response to demand by ethnic groups for a campus in their jurisdiction. Thus, while he espoused corporate-style management of universities, his expansion strategy was laced with ethnic politics of university ownership. He awarded charters for establishment of public universities in response to pressure from ethnic groups seeking universities in their locality.

In pursuit of the impossible

The benefits of Kibaki’s education reforms were less obvious than many of the transformative economic blueprint which delivered considerable benefits to the country.

He wanted to achieve the impossible in education: pursue equity through expanded access while infusing excellence through neoliberalism. But the lack of a focused and clear strategy only magnified the unintended consequences.

Ishmael Munene does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.