This article contains content about suicide.

A stockpile of Nembutal, a mysterious chronic illness, entrenched schoolyard bullying, overt racism, at least one failed relationship, and intergenerational trauma. These are all in the opening pages of Khin Myint’s debut memoir, Fragile Creatures. He lets the reader know what’s coming.

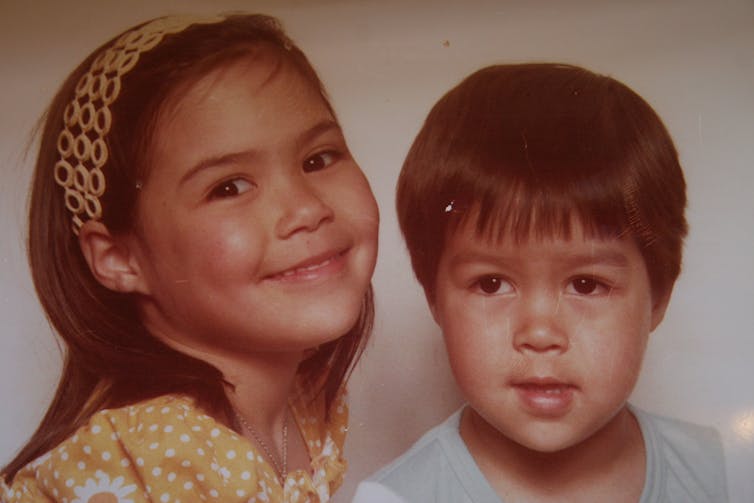

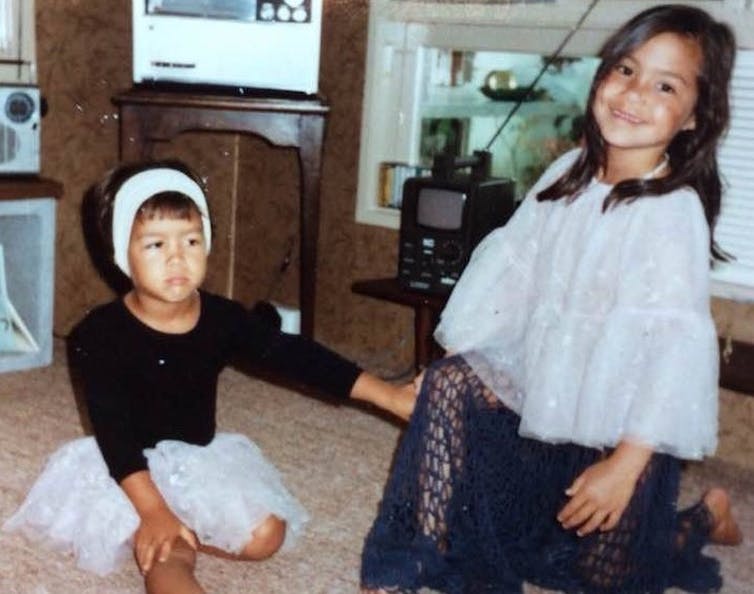

Myint and his older sister, Theda, grew up in Perth in the 1980s and ’90s, where their experience of primary and high school was traumatic. They not only experienced the brutal nature of chronic schoolyard bullying, but lived with the ongoing breakdown of their parents’ marriage.

Review: Fragile Creatures – Khin Myint (Black Inc.)

Their father was a Burmese refugee, their mother a migrant from the United Kingdom. Neither had a family network to support them to raise children or navigate the biting racism (in some cases, institutionalised racism) their family would face.

Structurally, the chapters alternate between recounting their childhood experiences and Theda’s ongoing chronic illness, as well as the breakdown of Myint’s engagement to Rachel, an American woman. (His experiences in the United States, as well as being central to his story, enable the memoir to compare Australian and American racism.)

These storylines eventually meet when Theda, exhausted after 13 years of illness and chronic pain, chooses to take her own life in 2013.

‘Not a happy’ childhood

I hesitated to write a trigger warning for this piece, as it seems to go against the intention of Myint’s memoir. He writes: “a society that pathologically refuses to talk about suicide despite the rising rates (and many citizens who struggle with compulsive suicidal thoughts) is what truly warrants a trigger warning”.

Myint’s childhood was not a happy one, and there are many possible seeds of childhood trauma, both within the home and outside it. He writes:

Dad had checked out by the time I was about ten. He lived in the same house, but we didn’t see him much. He called Theda and me “You Westerners” and told us we weren’t Burmese enough. He was black and Mum was white, and Theda and I were more like Mum even though we looked half like Dad.

Fragile Creatures brings to the fore one of Australia’s many silences (including in the curriculum of our schools). “My parents never talked about racism, and I don’t recall a single class at school that talked about Asian immigration, which is ridiculous because it was happening all around us.”

That silence is refracted through the lens of memory and the point of view of a child, but the relationship between Myint’s Burmese father and British mother was fractured with cultural difference and perhaps sexism and racism. The children witnessed it all.

At school, this division was intensified. Children, clearly learning from their own parents, bullied all who were different, with an intensity only found in the closed environs of school. This was a time when white supremacist Jack van Tongeren (leader of the neo-Nazi Australian Nationalist Movement) plastered nearly half a million racist posters around Perth.

Myint remembers: “White kids sat gender-separated and were boisterous compared to the docile Asians who spoke in their whiny-nattery banter that the white kids called ‘Chinese’”.

Myint’s understanding of history is apparent in sentences such as: “Mixed-race children weren’t illegal, but why had my parents thought it was a good idea to bring my sister and me into existence?” While not made explicit in the text, the idea of illegality recalls the growing diaspora of South African migrants to Perth.

I never once met another half-Asian in the small world I lived in. I never once saw mixed-race families. I never once met another Asian person whose only spoken language was English. Theda and I were the only ones, and we were monsters for it.

Racism is a scourge, and it manifests differently, not only in different times and locations, but between different peoples. Myint’s memory of a schoolyard conversation with Liam, an Irish boy who bullies Myint, is fascinating. Perth, Liam notes, “is racist as fuck”.

Between mental and physical illness

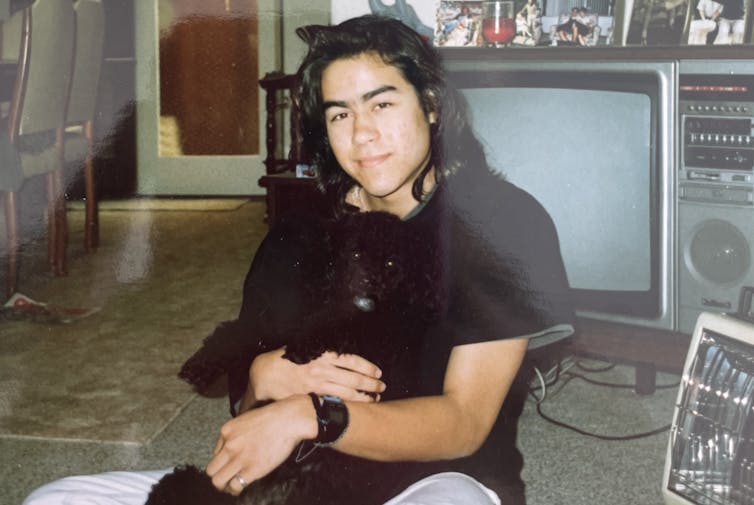

Theda’s illness began with an eating disorder, which manifested in her teenage years. Once she fell ill, she stayed ill, until her death. Her condition morphed and changed, defying a settled diagnosis. Myint recounts, “once she’d been vivacious; now she was withered like an old lady”.

Her symptoms included chronic nerve pain, light and sound sensitivity, and most debilitating of all, extreme fatigue. She required ongoing care, which – as is so often the case – fell to her mother. She also experienced repeated episodes of psychosis, which necessitated hospitalisation. Myint, like many family and carers, experienced the grey world of a stigmatised condition, remembering how her illness “placed her uncomfortably between mental and physical illness”.

The illness caused fractions within the family unit, as it does in so many families. Myint remembers, “I couldn’t stop the feeling that I was watching my sister’s illness kill our mother”.

These daily difficulties are compounded when symptoms and experiences of patients are dismissed, medicalised or stigmatised. Theda experiences all three. Her diagnoses move between chronic fatigue syndrome (or myalgic encephalomyelitis), psychosis and Lyme disease.

As a white woman reviewer, I do not have Myint’s experience. Given my own chronic illness, mine is more akin to (some of) Theda’s experience. I have no doubt this influences my reading of Myint’s (second-hand) exploration of chronic illness, including the medicalisation of the experience of being ill, and the lifelong impacts of illness on carers.

His is a keenly needed perspective in contemporary Australia, bringing to the fore the complexities of families facing love, illness and death.

The relationship breakdown with Myint’s American fiance, Rachel, is brutal. Apparently happy with plans to stay in Australia, she makes a snap decision to leave the relationship and return to the United States with little explanation, and finally breaks up with him from there, over Skype. Rachel is not a sympathetic figure, but her presence in the memoir (and Myint’s life) enables Australian racism to be contrasted with American racism.

At one point, she reveals to Myint how she, as a white female American, perceives the silence around racism in Australia:

It’s all – No worries. All good, mate. No drama. That’s how Australians do it. Whenever I start talking about anything uncomfortable, they scatter dismissive slang like that, as if they’re tossing grenades, desperately trying to stop me.

He follows Rachel to the US, to either save their relationship or understand what happened, at the same time Trayvon Martin’s killing by a neighbourhood watch volunteer (who reported him to police as “real suspicious” and then shot him, claiming self-defence) was in the news. Soon after, Rachel pulls what I can only describe as “a Karen”. Myint quotes her as telling him: “all I have to do, Khin, is tell the police that I don’t want you here and you’ll have to leave”.

She follows through, taking out a protection order against him and alleging “stalking”. He is forced to undergo a trial and hire a lawyer to avoid potentially being banned from the US for life.

Writers, not doctors

Myint observes: “what defines racism isn’t who gets targeted; it is the unconscious anxieties of the more racially privileged group that targets them”. This is true, for both Australia and the US.

Gender studies scholar Judith Butler and author bell hooks, who wrote about race, gender and class, both get a mention in Fragile Creatures, as does the work of Australian writer Lucia Osborne-Crowley, who writes about sexual assault and trauma.

Myint turns to writers – not doctors – to understand the effect of trauma on the body. Remembering his high-school years, he writes “if most of your peers want you to suffer on an ongoing basis, the effect is a growing feeling of shame, and it becomes intolerable”.

As an adult, he enrols in a creative writing course, yet finds the system unwelcoming. “I found the language used to deconstruct ‘normality’ alienating and elitist. All the lecturers were white, upper-class and pretentious in my estimation.” In Fragile Creatures, Myint talks back to this elitism.

Myint was a participant in the Wheeler Centre’s Next Chapter scheme in 2020, and he has been writing since his teenage years. Perhaps it is even a form of healing. He states, “writing about things gave them shape, and even though I abstracted emotions into words on a page, that shape made those things easier to feel in my body”.

This is Myint’s memoir. It can be no one else’s. But his family’s combined trauma – Theda’s, his mother’s, his father’s – is present on every page, fuelling his dissections of both racism and the stigma of illness and caring.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Astrid Edwards does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.