Sir Keir Starmer, the UK’s new prime minister, brings an impressive CV: barrister, former director of public prosecutions and ex-shadow Brexit secretary. An establishment insider who knows his way around the corridors of power, he is no stranger to leadership. But that does not necessarily make him a good leader, nor even indicate his potential to become one. Being a member of a privileged elite might land you a plum job, but it does not make you good at it.

Our ancient Welsh forebears knew this well, telling stories to expose bad and promote good uses of power, as my research has shown. Starmer could do a lot worse than to read the Four Branches of the Mabinogion from Welsh mythology during his first few weeks in office. From those skilfully fashioned tales of lordship, he might learn a lot about how to conduct himself as head of government. And, crucially, how not to.

English translations of the Four Branches, along with seven other unconnected stories found in two medieval manuscripts – The White Book of Rhydderch (circa 1350) and The Red Book of Hergest (circa 1382) – appeared as part of Lady Charlotte Guest’s Mabinogion (1847-49). She was an English aristocrat and first publisher in modern print format of the Mabinogion.

Unlike the other tales in Guest’s compendium, those of Pwyll, Branwen, Manawydan and Math each form part of a cycle of interlacing stories. Although medieval compositions, they appear to draw on more ancient material and to be set in pre-Roman times.

Weaving magical practices and otherworldly encounters into stories of prehistoric ruling elites, their conflicts, crimes, misdemeanours and redemptive acts, the Four Branches are sometimes thought to bear traces of a pre-Christian mythology native to Britain.

At least one scholar has suggested that the Four Branches were written as a kind of manual for princes. It is not difficult to see why. Each story in the cycle includes examples of bad rule and of good, and their consequences.

The fourth branch tells of the nephews of a ruler, Math, who rape their uncle’s footmaiden, Goewin. The terrible effects of their corruption spread virally across two kingdoms, bringing in their trail betrayal, humiliation, murder and war.

But there is good leadership, too. Math imposes harsh, magical penance on his nephews and accepts responsibility for what has happened to Goewin. Rather than treating the punishment of his nephews as the fulfilment of the demands of justice, he takes the burden of recompense upon himself, offering to marry the abused woman and yielding power over his kingdom to her.

This suggests a belief that if power is in your hands, then you should take responsibility not only for your own actions, but also for the actions of those you lead, be they family members or functionaries. Sadly, nothing would seem further removed from the blame and shame culture of modern British politics.

Read more: Keir Starmer: what we know about Britain's new prime minister and how he will lead

If the case of Math and Goewin is the most dramatic and shocking lesson in the exercise of lordship in the Four Branches, it is not the only tale which might give the new PM pause.

In the first branch, we meet Pwyll, Lord of Dyfed. He commits various errors which result from poor judgment and impetuous actions, the consequences of which are wide-reaching and continue into the next generation. His first error involves failing to observe the etiquette of the hunt in allowing his hounds to feed on a stag felled by another king’s pack. The offended monarch turns out to be Arawn, ruler of Annwfn (the Otherworld).

To compensate for his behaviour, Pwyll is required to change places with Arawn for a year and a day, and to defeat the latter’s mortal enemy in single combat. When he finally returns to his own court, price paid, he finds that his subjects have not missed him because Arawn, in his likeness, has been a much better ruler than he was. Better because he was more generous and more willing to share fully the joys and hardships of his people.

But Pwyll fails to learn the lesson and remains a man who acts and speaks without thinking. Following a magical encounter with the mysterious Rhiannon, the two agree to marry. A feast is thrown at her father’s court to celebrate, but the man she has rejected as a suitor turns up. Without thinking, Pwyll greets him and offers him anything in his power to grant. He asks, of course, for the hand of Rhiannon. She, then, has to contrive her own rescue by playing a trick.

Gwawl, the unfortunate suitor, is trapped in a bag and made to bargain his way out by withdrawing his claim to Rhiannon. Pwyll, still an unwise and thoughtless ruler, allows his men to beat Gwawl while he is in the bag and unable to defend himself.

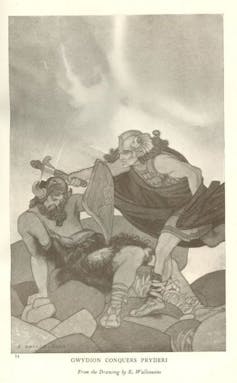

In the third branch, this unbecoming behaviour comes to haunt his widow and their son Pryderi, when their land is cursed and their crops destroyed by a magician who has made himself Gwawl’s avenger.

Wisdom

The Mabinogion could remind the new prime minister that true leadership requires not just the exercise of power but the wisdom to use it judiciously, the humility to learn from mistakes and the courage to take responsibility for one’s actions and those of one’s subordinates.

As Starmer navigates the complex political landscape, these ancient narratives could serve as a valuable compass, ensuring that his tenure is marked by justice, compassion and a genuine commitment to the wellbeing of the country.

Kevin Mills does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.