South African writer Juby Mayet passed away in 2019 at the age of 82. She wrote her autobiography in 1997 but it has only now been published, 25 years later. Freedom Writer: My Life and Times finally places the spotlight on an outstanding figure in South African journalism.

Mayet was a reporter in Johannesburg from 1957 until 1978, and during those two decades she wrote for important popular and political publications. These included the tabloid newspaper Golden City Post, the famous Drum magazine, the UBJ Bulletin published by the anti-apartheid Union of Black Journalists, and the anti-apartheid periodical The Voice.

For Black South Africans, apartheid society was exploitative, violent and demeaning, which made publications produced by Black writers culturally and politically essential. Blacks saw themselves and their experiences represented in ways they recognised and appreciated by Golden City Post and Drum. The UBJ Bulletin and The Voice dared to publish openly critical reports about the apartheid regime’s brutality.

Starting in the late 1960s, Mayet also became a leading anti-apartheid reporter – she preferred the term “freedom writer” – who used her typewriter to speak truth to power and suffered the consequences.

Read more: Journalism of Drum's heyday remains cause for celebration - 70 years later

I first met Mayet in 2018 when I interviewed her about her coverage in the 1960s of prosecutions of “mixed” couples who contravened the Immorality Act, the infamous apartheid law that made it illegal to have extra-marital sex across the colour line. I quickly realised what an impressive person she was and how significant a reporter she had been.

As a historian, I have long been writing about women whose skilful and courageous efforts to navigate life in patriarchal South African society have gone largely unnoticed. Mayet, too, has been overlooked, in her case by researchers who celebrate South Africa’s rich history of journalism and literature. For example, Drum magazine in the 1950s and 1960s is known for producing iconic male Black writers like Can Themba, Bloke Modisane and others. But Mayet, too, was a graduate of the “Drum School of Journalism”. She was there, in plain sight, yet somehow invisible to researchers.

Fortunately, her autobiography has now been published, along with an afterword I wrote to provide more details about her achievements. I hope she will now get the public attention she deserves.

Imprinted by Fietas

Mayet was born in 1937 to a Malay family, a group categorised as Coloured under apartheid. Her autobiography tells of how she was raised in Fietas, a neighbourhood near downtown Johannesburg, the country’s economic hub. Originally designated as a Malay location, Fietas was destroyed and rezoned a “white” neighbourhood after passage of the Group Areas Act (1950).

Fietas was where Mayet developed her cosmopolitan sensibility. The small, vibrant community was culturally diverse; Malays, Indians, Coloureds and some poor whites co-existed peacefully. She was raised Muslim but, she writes, “as a kid, growing up in slums where people lived together, mixed”, she had neighbours, friends and a sweetheart from different cultural and religious backgrounds. Fietas taught her to look beyond race labels, and its imprint on her psyche helps explain her lifelong hatred of apartheid, which sought to differentiate and distance people from one another.

Discovering the wonder of words

Mayet always loved reading and wanted to be a writer. She began composing short stories as a teenager and, remarkably, her first was published when she was just 17. Already she had “long ago made up my mind that I was not going to get married and settle down into the rut that I saw so many women finding themselves in”.

Her big break came when she was hired to do freelance work for Golden City Post. She impressed senior staff and the owner of the Post and Drum, Jim Bailey, who personally hired her as a cub reporter in 1957. She said she always felt like she worked for both publications because they shared staff and offices, and encouraged a joint readership.

She began by covering social and community events, and writing advice columns for adolescents and women, offering recipes and fashion tips. In the 1960s she worked full time for Drum where, she writes, “I really found my wings” as a writer. She started writing feature articles, opinion pieces, short stories, poetry and more.

The freedom fighter

Over time, Mayet’s work became overtly political. Some of the stories she was most proud of were about leading Black anti-apartheid activists who she admired, like Robert Sobukwe and Nontsikelelo Biko, Steve Biko’s widow.

Mayet became a reporter when journalism was a male domain and sexist profession. The famed literary renaissance of Sophiatown, a legendary Black neighbourhood also destroyed and rezoned and of which Drum and the Post were part, had been relentlessly macho. Historian Rob Nixon called it “airlessly male and sometimes misogynistic”. Drum made her a cover girl in 1957, something she did not want to be. She wanted to be seen the way she saw herself, as a serious writer. Almost from the start, she criticised sexist traditions and attitudes that limited girls’ imaginations and women’s life choices.

In the 1960s she started mocking and then openly criticising apartheid ideology and laws in her reports, columns and short stories.

She joined the Union of Black Journalists in 1973 and it soon “became my life”. She helped publish the UBJ Bulletin, banned after its coverage of the 1976 Soweto uprising, and then The Voice. In 1978 she was arrested for contravening the Internal Security Act and spent nearly five months in detention without trial. After her release, she was “banned”, making it illegal for her to appear or speak in public and for the press to publish or report her words. These acts of reprisal by the regime caused her and her family intense emotional and financial hardship and destroyed her career.

Time to remember Juby Mayet

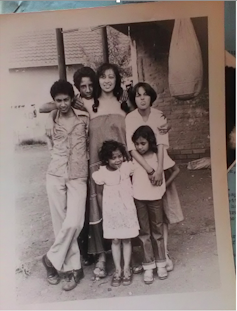

The fact that Mayet, a self-described “extremely shy” girl of colour from a poor family, had the temerity to pursue her desire to be a writer in apartheid-era South Africa is remarkable. The fact that she succeeded in forging a career documenting the absurdities and cruelties of apartheid in the male-dominated, sexist world of journalism is extraordinary. The fact that she did so as a widow raising eight children on a Black reporter’s paycheck is nothing short of incredible.

Her career has been neglected in part because she was severely modest. After writing her autobiography in 1997 she did not try to get it published because, she said, she doubted people would want to read about her.

Thankfully Jacana Media, an independent South African publishing house, has brought her autobiography to life.

Mayet is long overdue for serious consideration as a writer. Hopefully her autobiography will ensure she finally wins the recognition and admiration she deserves.

Susanne M. Klausen has received support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada with an Insight Grant (2016, Grant #435-2016-1162), the Gerda Henkel Foundation with a research fellowship (2018, Grant #AZ 36/V/18), and the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study (NIAS) with an individual fellowship (2019–20).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.