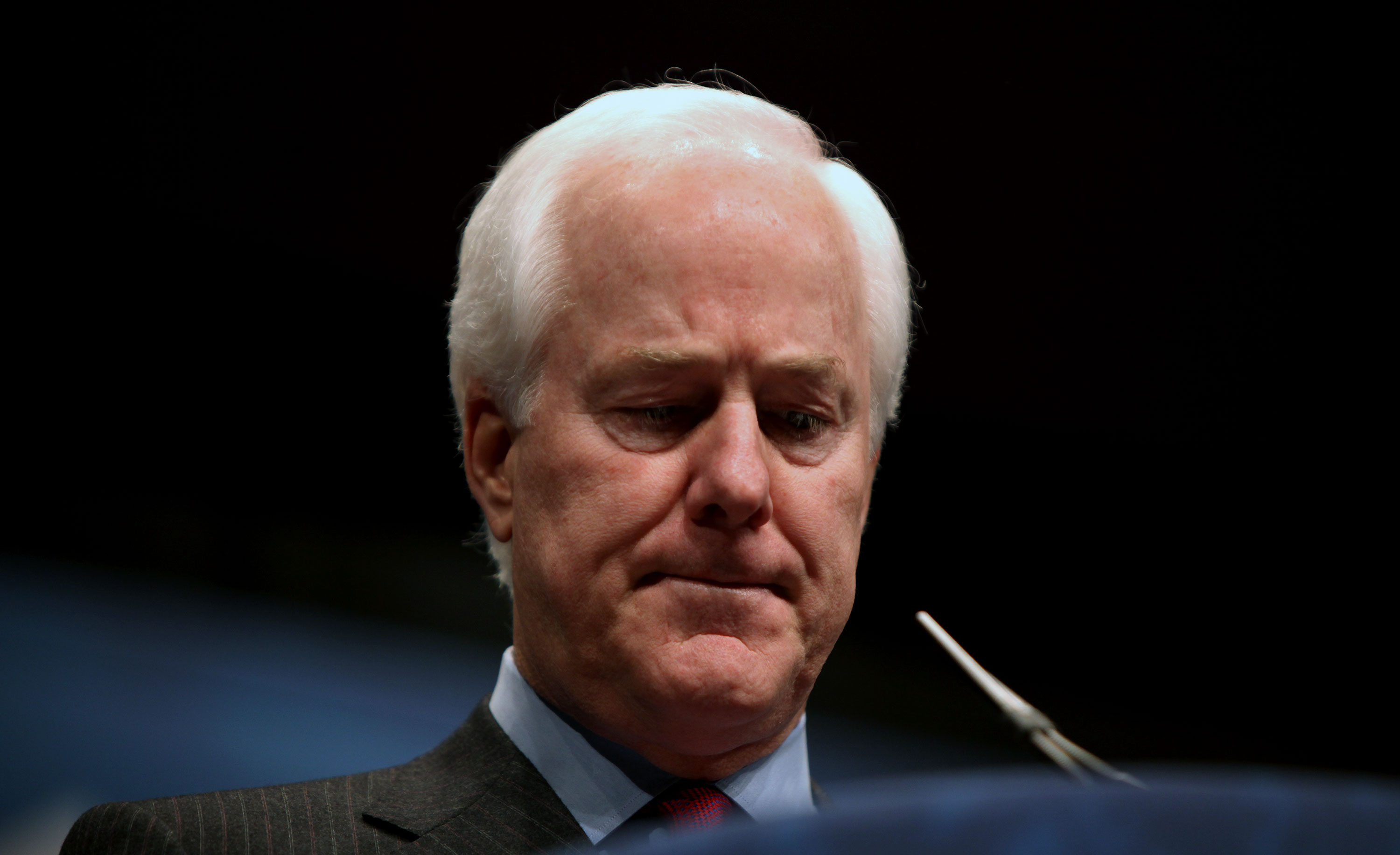

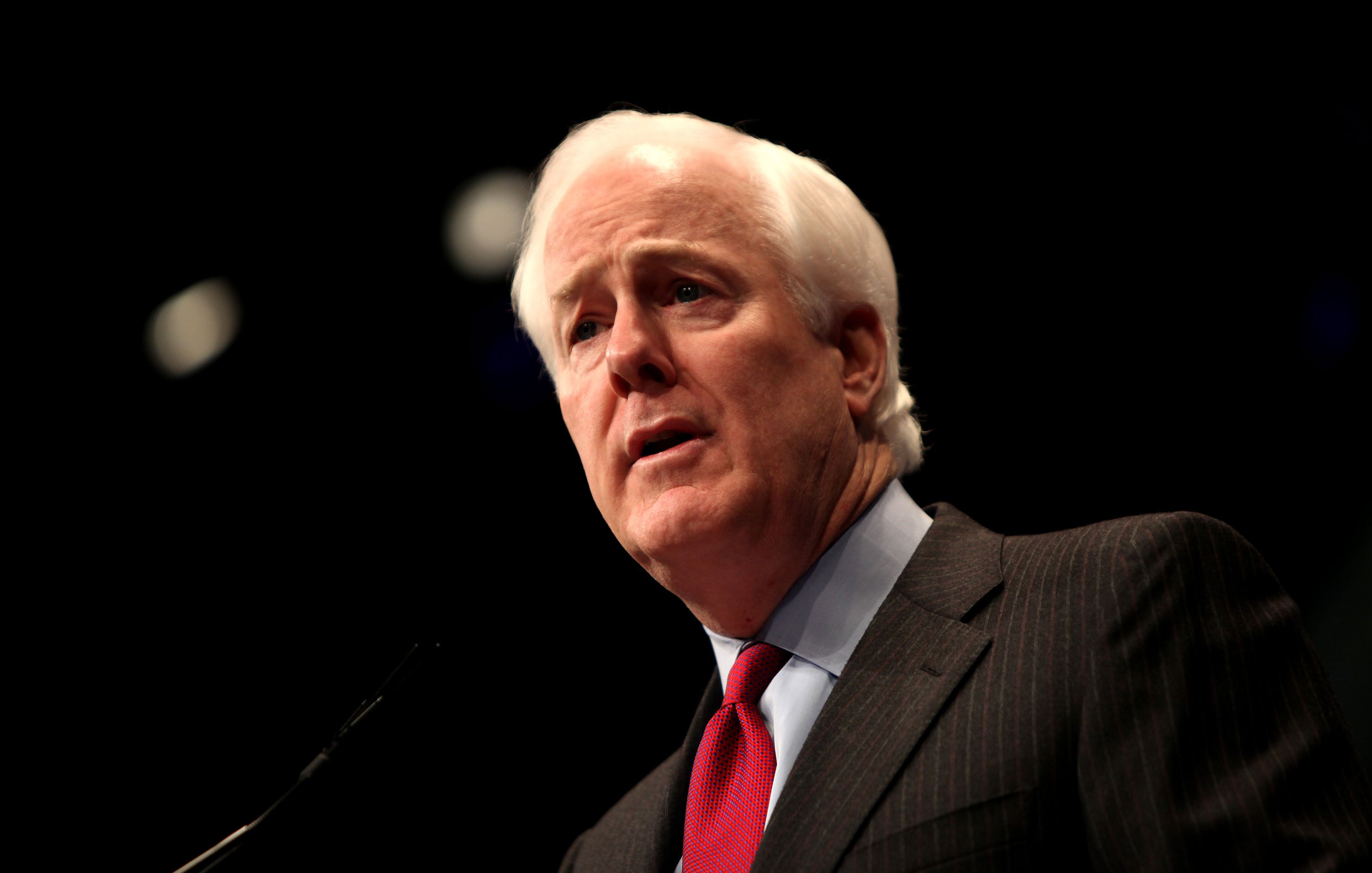

On a June afternoon in 2007, U.S. Senator John Cornyn sounded eminently reasonable. In a floor speech, the rangy, snow-haired Texan said that of all the legislative issues he’d wrangled with during his four and a half years in the Senate, immigration reform had produced the most controversy. “Passion,” he avowed, “can produce more heat than light, but what we need is some light and some clear thinking and some better solutions to our broken borders and our broken immigration system.”

Less than two hours before, Cornyn had voted against a comprehensive immigration reform bill, the fruit of months of bipartisan negotiations and a Hail Mary attempt to salvage President George W. Bush’s otherwise disastrous second term. The measure died by a tally of 46-53.

Frank Sharry, a long-time immigration reform advocate, had decamped with allies to a bar near the Capitol to mourn the bill’s defeat. When the senator from Texas appeared on a television screen, Sharry’s blood pressure rose. “We’re sitting there just heartbroken; this was probably the last chance we would have for reform for many, many years,” said Sharry, now director of the pro-immigrant nonprofit America’s Voice. “And who takes to the floor? John Cornyn, to give a 15-minute speech on the need for immigration reform. I swear to God, if I could have reached through the TV and throttled the motherfucker, I would have.”

If that reaction seems a tad trenchant, consider that Cornyn’s 2007 vote was part of a pattern. Throughout the years, the Houston native claimed to be open to comprehensive immigration reform. When Cornyn took over the Senate’s immigration subcommittee in 2005, he wrote: “We must address the need for better border security … while acknowledging the important contributions that immigrants make to our economy.” The anti-immigrant Federation for American Immigration Reform bemoaned his ascension to chairman, while the pro-immigrant organization the National Immigration Forum saw it as “a hopeful sign.”

But a gulf would open between the senator’s actions and words. In 2006, 2007, and 2013, Cornyn voted against hard-fought compromises that made it to the Senate floor and, in his critics’ eyes, further undermined the bills through grandstanding and bad faith amendments.

Many casual observers don’t know what to make of Cornyn, who’s up for re-election next year: A recent poll found that nearly a third of Texans have no opinion of him whatsoever. With his dry wit and genteel manner, Cornyn comes off as inoffensive, if a bit arrogant. But his immigration record suggests a politician closer to Jeff Sessions than John McCain, more Ted Cruz than Jeff Flake. Just ask the hundreds of thousands of undocumented Texans who live in the same shadows they did in late 2002, when Cornyn took office.

“He talks a good game, but his behavior does not demonstrate that he was serious about reform,” said Cecilia Muñoz, a former advocate with the National Council of La Raza and later a top Obama policy advisor. “As a result, we’ve been living with a broken system for his entire tenure in the Senate.”

*

Though he wasn’t always precise on the details, George W. Bush wanted immigration reform. The chamber-friendly Texan was eager to deliver for both his business allies and his many Hispanic supporters. September 11 put the kibosh on such dovishness soon after he took office, but Bush revived the matter in the run-up to his re-election campaign. In January 2004, he began calling for Congress to make a deal.

In 2005, Cornyn began working on a bill with Arizona Republican John Kyl. But a more formidable duo was also at work: McCain, Arizona’s better-known senator, and Massachusetts Democrat Ted Kennedy. McCain and Kennedy released their proposal months ahead of Cornyn and Kyl, and their bipartisan plan eclipsed the latter’s more conservative offering. By spring of 2006, Bush was publicly signaling his support for the McCain-Kennedy deal—opening a rare rift between the president and his home state’s junior senator.

Cornyn had ridden Bush’s coattails to power and defended the president’s worst policies. In 2005, Cornyn was one of only nine senators to side with the White House against a McCain-led ban on cruel and inhumane treatment of war prisoners. Which is to say, Cornyn stood by Bush on torture, but a slightly-too-liberal immigration bill was a bridge too far.

Cornyn had two major bones to pick with the McCain-Kennedy bill: The measure put most undocumented immigrants in America on a path to citizenship without making them leave the country first, and its new work visa program allowed many more to also transition to citizenship. Cornyn wanted a visa program that didn’t lead to permanent status, and under his legislation undocumented immigrants already in the country would have had to return to their home country and apply from there. McCain lambasted Cornyn’s plan. “The reality is, 11 million people are not going to voluntarily come out of the shadows just to be shipped home,” McCain said. “Report-to-deport is not a reality, and it isn’t workable.”

In May 2006, Cornyn voted no on McCain-Kennedy. The bill passed anyway, 62-36, with support from such wild-eyed liberals as Lindsay Graham, Sam Brownback, and Mitch McConnell.

Ultimately, it was the GOP-controlled House that killed reform in 2006. House Republicans had passed their own bill in late 2005 that was all crackdown with nothing for the pro-immigrant side, and they refused to consider the Senate measure. With a tough midterm looming, the GOP conference had no appetite for compromise. (They would be, it bears noting, wiped out anyway.) Cornyn’s defenders say he had correctly read the lower chamber and pushed for a bill that might survive there. “He was trying to assess the House,” said John Feehery, a political consultant and former press secretary for Republican House Speaker Denny Hastert. “He was trying to thread a fine needle … I always saw him as a force trying to find a middle ground.”

But immigrant advocates disagree. If Cornyn wanted reform, they argue, he should have supported the bipartisan legislation and used his role to nudge House Republicans toward compromise. Instead, his vote was “a signal to many House members who were on the fence: If a border-state, moderate-sounding senator can’t get to ‘yes,’ maybe it’s not for me,” Sharry said.

Then there was 2007. This time, Cornyn and Kyl joined the group negotiating a new reform bill, but the former didn’t last long. In May of that year, in an ornate Capitol meeting room, Cornyn was pushing for harsher deportation measures when McCain reportedly burst out: “This is chickenshit,” and suggested the Texas senator was trying to tank the deal. The exchange continued until eventually McCain, then a presidential candidate, delivered a hearty “fuck you.” In a later interview, Cornyn joked: “I didn’t so much walk away … as got chased away.”

But Kyl stayed in, and the bill that emerged was more conservative than its 2006 predecessor. The new measure’s visa program didn’t allow most workers to transition to permanent status; it also introduced border security “triggers,” requirements that a new border wall and agents be deployed and the government achieve full “operational control” of the U.S.-Mexico divide before anyone got permanent status; it even forced already present heads of household to return home before qualifying for a green card, a nod to Cornyn’s hobby horse from the year prior.

Still, Cornyn wouldn’t bite. He decided the bill needed to exclude immigrants who had outstanding deportation orders or who’d returned to America after being removed—a group numbering at least 600,000. Cornyn dramatized those victimless crimes, saying the migrants had “thumbed their noses at the law,” but the bill’s negotiators thwarted him, calling the amendment a deal-killer. In June 2007, Cornyn voted against the final bill, which failed to pass the Senate. (In a bid to bring in more Republicans, the measure had hemorrhaged liberal backing: 15 Democrats opposed it, plus Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who criticized the measure on labor grounds.)

“If John Cornyn was ever going to vote for an immigration reform bill, that was the one,” Sharry said. That year, Cornyn was condemned by the El Paso Times and the Dallas Morning News for abandoning the president and Texas’ large immigrant population. Later that year, Massey Villarreal, an ex-chair of the Republican National Hispanic Assembly, joined the chorus of disapproval. “Cornyn has joined the ranks of the know-nothing, do-nothing obstructionists who refuse to deal with the immigration issue in a manner that will lead to responsible and practical reform,” Villarreal wrote.

Just months after his “no” vote, Cornyn issued a warning to GOP candidates that seemed to encapsulate his political approach. “My suggestion to those engaging in the Republican primary battle is to be very careful that you don’t give the wrong impression by either how you talk about [immigration] or the tone you use,” he said. “It can quickly get out of hand if you’re not careful.”

The 2007 bill’s collapse killed Bush’s dream of adding immigration reform to his legacy. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, head of the newly Democratic lower chamber, declined to pursue a House version, preferring to shield freshly elected moderates in her caucus from controversy. With full reform off the table, Democrats tried twice, in late 2007 and 2010, to pass a stand-alone DREAM Act—legislation that would only furnish status to those brought to America as children. Despite previous support, Cornyn voted against both bills, claiming the legislation should be part of a larger reform package—such as those he’d already voted against.

For Sharry, Cornyn’s actions were utterly calculated: The senator wanted to please big business and Hispanic Republicans without alienating an ever-more revanchist base. “So he’ll talk a good game, make sure he gets to ‘no,’ and therefore preserve his electability in Texas,” Sharry said. Feehery, the Republican consultant, had a somewhat different take. “Cornyn’s somebody who would like to make legislative progress on an issue, but he also doesn’t want to commit political hari-kari,” he said, adding that Bush’s approval ratings were in the tank by 2006, so pulling away from the president bore little political cost.

By 2013, when reform resurfaced, Cornyn’s tune had grown familiar. After Obama’s 2012 blowout victory, a Republican National Committee autopsy report said the party had to back immigration reform or perish. A team of senators again crafted a proposal, and Cornyn again balked, this time saying the border security “triggers” needed to be stronger. The bill passed without his support, 68-32.

According to a Politico post-mortem, the 2013 effort had serious legs in the Republican House. But a campaign led by the GOP’s staunchest nativists—Iowa Congressman Steve King, then-Senator Jeff Sessions, and his now infamous aide Stephen Miller—destabilized support. Cornyn, befitting his style, didn’t meddle in the lower chamber, but he hurt the cause in two ways: He dragged out Senate deliberations with long speeches against the bill and he helped thwart a symbolic goal, set by the bill’s negotiators, to reach 70 votes. The New York Times editorial board named Cornyn as an ally of Sessions in trying to kill the deal.

Cornyn did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

*

Trump’s election, and his decision to take immigration cues from the borderline white nationalist Miller, has shunted comprehensive reform aside. These days, immigrant advocates spend their days scrambling to put out fires, rather than pushing a proactive agenda.

In late 2017, after then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced an end to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals—the Obama-era directive that shielded migrants brought to America as children—Cornyn threw himself into the fray to find a fix. But in the end, Cornyn backed a Trump proposal that included a right-wing Christmas list of anti-immigrant provisions, rather than competing measures that stood a chance at Senate passage. In a legislative bloodbath, all proposals failed—leaving the so-called Dreamers in the lurch.

Now Cornyn faces a tough re-election fight. An army of little-known Democrats has declared challenges, encouraged by Beto O’Rourke’s near-defeat of Cruz in 2018. In Trump’s ongoing impeachment saga, Cornyn has become an unscrupulous defender of the president. But he’s always shied from Trump’s more incendiary rhetoric about migrants and the border. On immigration, Texas voters may want to consider Cornyn’s record, not just his words.

Asked about immigration reform earlier this year, Cornyn struck a wistful note. “It’s the same old story, isn’t it?” he said. “It’ll break your heart; we never quite get to the finish line.”

Perhaps the senator’s grief is legitimate. It’s surely dwarfed, though, by the regret of America’s 11 million undocumented residents, who remain in limbo after all his years in office.

Read more from the Observer:

-

Texas Congressional Candidate Shannon Hutcheson Defended Corporations Against the Vulnerable. EMILY’s List Endorsed Her Anyway: Shannon Hutcheson has billed herself as a fierce reproductive rights advocate. But the corporate lawyer has papered over a troubling record, including her defense of a prison guard who sexually abused migrant women.

-

Activists Rally for the Closure of Hutto Detention Center as Private Contract Rumors Swirl: Former detainees were among those criticizing ICE’s attempt to secure a 10-year private contract for the facility and two others in Texas.

-

‘You Can Only Take So Much’: Low-Income Hurricane Harvey Survivors Sue Over ‘Discriminatory’ Recovery Process: The lawsuit accuses state and federal officials of favoring wealthier, white homeowners over poorer black and Hispanic renters.