Collectors can be withdrawn and secretive creatures, as jealously protective of their possessions as Tolkien’s dragon Smaug was of its gold. This was not Joe Bussard’s style at all. Over more than 50 years he built an exceptional collection of American vernacular music – old-time country music, blues, jazz – on 78rpm discs, and he enjoyed nothing more than sharing it with others. Joe, who has died aged 86, played the records on his Country Classics radio show, he taped them for fans and researchers at 50 cents a track, and he lent them to labels that were committed to reissuing the music of the past, so that enthusiasts all over the world could hear fabulously rare, sometimes unique, recordings for the price of an LP or CD.

In “Joe’s Basement”, the 30ft storehouse of shellac beneath his home, he entertained an endless procession of visitors, spinning records he wanted them to hear and telling stories about where he had found them: “This old stone house down the hollow … This old shotgun shack … This little old coal town, forgotten long ago …”

“Joe doesn’t just listen to his records, he actively participates,” wrote the fellow collector Marshall Wyatt when he reissued some of them on his Old Hat label in 2002, on the CD Down in the Basement. “He’s snapping his fingers, jiving, keeping time with his whole body, and smoking his cigar all the while. He picks up the record sleeve, fanning imaginary flames that leap from the turntable. ‘This is one hot record!’ Every record has a story, and every story is like a theatrical performance, with Joe playing all the parts.”

The exuberance of Joe’s interaction with his records is brilliantly captured in Edward Gillan’s 2003 documentary Desperate Man Blues, interspersed with tributes from performers and listeners whose horizons were redefined by the music he secured before it was lost. “When you stop at Joe’s,” his musician friend Paul Geremia said, “it’s like going to a museum.” Joe himself, no lover of museums, would simply grin. “You can’t say you don’t have fun when you come down here!”

Joe was born in Frederick, Maryland, to Joseph Bussard Sr (it was pronounced not Buzzard but Bersard), who ran a farm-supply business, and Viola (nee Culler). As a boy Joe liked Gene Autry, but when he was 11 he heard a record of the pioneering country music singer Jimmie Rodgers – it was a bombshell moment that reshaped the terrain of his life.

Having dropped out of high school, he financed his record-gathering by working in the family business and at other jobs; he also spent eight years in the National Guard.

In the 1950s, he began to take long collecting trips into Virginia, West Virginia and Ohio, and down into the south-eastern states. He claimed he could glance at a house and tell, from how it was kept, whether there might be records inside. “I’d go from door to door, house to house, and it was nothing to go out and in one weekend to come back with four, five hundred records.”

In later years, the duplicates he acquired in these ventures became another source of income. He liked to tell the story of how the band Canned Heat, whose Bob Hite and Henry Vestine were themselves noted collectors, dropped in one day, flush from one of their hit records, with “wads of money, enough to choke an elephant! By the time they were done, they dropped $9,000. In cash!” So he bought a swimming pool.

Joe’s tastes were wide, but not limitless. Country music and blues of the 1920s and 30s were his passion. Jazz, too, but only up to the Depression; he would say bluntly that, for him, jazz died in about 1933. Of the music made since the second world war, he approved of bluegrass but scorned rock’n’roll (“the cancer of music”), and he dismissed all subsequent pop as inconsequential noise.

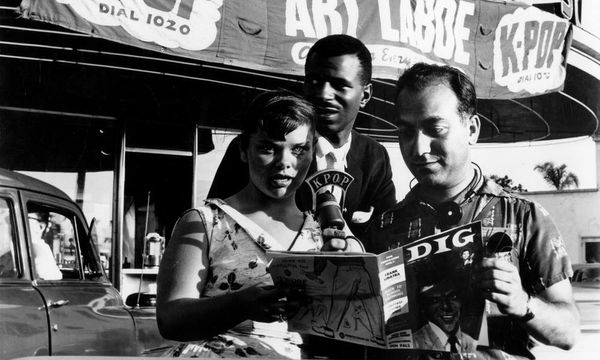

His response to the 45rpm record was to create his own label, Fonotone, hand-pressing 78rpm discs with a vintage record stamper and handwriting the labels. It lasted from 1956 to 1970, its catalogue embracing obscure rural musicians Joe had come across; himself, playing guitar, banjo or mandolin, with his friends, sometimes as Jolly Joe’s Jug Band; and collector-musicians such as Mike Seeger, Mike Stewart and the young John Fahey, whose first recordings were made for Joe in 1959. The Fonotone years have been lovingly documented by Dust-to-Digital Records, presented – a detail Joe appreciated – in a mock cigar box.

It was even through records that he met his wife, Esther Mae Keith, a bluegrass enthusiast. They married in 1967; she died in 1999. Joe is survived by their daughter, Susannah, and three granddaughters.

• Joseph Edward Bussard Jr, record collector, born 11 July 1936; died 26 September 2022