Coming out and falling in love, from an extraordinary new memoir by an award-winning author "Sue, I’ve got something important to tell you after our lecture." This sounded more tantalising than I had intended, but I was worried she might slip out after the class and I would miss her.

"Okay,", she said, her interest piqued, "let’s go to the cafeteria for a quick cup of coffee afterwards. I’ve got half an hour before I have to pick up Katie from kindergarten."

"Great, let’s do that."

I didn’t hear a word the lecturer said. At the end I glanced down at my meagre page of notes and struggled to recall any of the slides she’d shown us. Sue would be the first person I’d tell. I was anxious about how it would change our friendship. My confession was a risk. I knew that. But I felt I couldn’t go on without telling someone, and she was a person I felt I could trust.

"What did you think of the lecture?" she asked me as we filed out of the front row at the end. (I hated the front row but she insisted on sitting there.)

"It was . . ." and I was just about to say "great", when I had to admit to myself that I hadn’t even registered the topic. "I was a bit distracted," I confessed, instead.

"Oh," Sue responded, looking concerned. "So, what was it that you wanted to tell me?" By this time, we were standing in the central vestibule outside the lecture theatre, where the mass of students mingled. The seething crowd had not yet dissipated. It wasn’t the right place to make a momentous admission, but I had stewed on it for so long, I believed it was better out than in.

"You can’t tell a soul," I began, as we pushed our way through the main entrance and along the asphalt path to the cafeteria. I glanced around to check we couldn’t be overheard.

"Not anyone, at all," I repeated, "but . . . I think I might be a lesbian." This wasn’t a word I found easy to say, so the effort to get it out was huge. In fact, it had taken me 33 years to get it out. I was the same age as Christ was when he was crucified: a fact that resonated with me then.

"So can lesbians get AIDS, then?" she asked. "If they can, I’d be careful."

Instead of recoiling in horror as I thought she might do, Sue laughed out loud. When she managed to control herself, she said: "That’s impossible. You’re just imagining it. It’s a phase, it’ll pass." For a moment I believed maybe she was right. I experienced a surge of relief, which was followed almost as quickly by a cold wave of despair. I wanted to believe her, but I knew I couldn’t.

"I’m afraid it’s true," I said after a long pause. "I don’t think it’s just a phase. I mean, I wish it was but, but I doubt it."

"Why do you doubt it? What makes you so sure, suddenly? How long have you been married?"

"Ten years."

"Well, surely you must know by now. Have you ever slept with a woman?" she asked, shifting to interrogation mode.

"No, never," I answered.

"Never," she repeated in disbelief.

"No," I responded, again, "never."

"How on earth would you know that you’re a lesbian, then?"

Her logic was flawless, but I was still unconvinced.

"It’s hard to explain. I guess I could be wrong, but for some reason marriage hasn’t worked for me. Maybe marriage to someone else would have been better, but I have tried hard to make it work and now it’s time to try something new."

"So can lesbians get AIDS, then?" she asked. "If they can, I’d be careful."

"I’m not planning to rush out and go to bed with the first woman I meet," I retorted. "Just because I’m a lesbian, it doesn’t make me a nymphomaniac."

"I was just wondering," she replied, "I’m only thinking of you — Oh my goodness, look at the time! If I don’t hurry up, I’ll be late to pick up Katie. Let’s keep in touch, okay?"

With that she was gone.

I was alone, and suddenly aware of my environment. Of the clattering and clanging of cutlery, trays and dishes: of the loud buzz of student voices punctuated by raucous laughter. It is strange how lonely you can feel in a crowd. I had been in their place once, full of optimism and plans. Like them I had visualised a future life, and now a decade on I was about to destroy it. I felt sick, diseased — wrong. If homosexuality was normal, then why wasn’t everyone doing it? In that moment I hated myself.

I thought of suicide, and eternal nothingness where I wouldn’t have to tell anyone. Not my husband, parents, children or friends. Perhaps it was the hum of hope and life in that cacophonous room that turned me around. I felt disconnected. I realised I needed to find a community. If that turned out to be a disappointment, I would kill myself, then.

I began going occasionally to the women’s bar when my night shift ended.

I went with a neighbourhood friend, ostensibly to dance, which I loved. Initially, I thought I had come to the wrong place because in the dim, mood lighting with its flashing strobe almost everyone looked as if they were male. It was a foreign world to me, but one which for some inexplicable reason felt right. I wasn’t there to cruise, but to reassure myself I wasn’t the only person in the world who felt the way I did. Like a leper who covers their deformity, I hid my secret. Things carried on normally on the outside, but inside me there was just turmoil. Change was inevitable, but please not now.

I made one fatal mistake. I patted Sue’s bottom the way I’d seen sportswomen do on the netball court, but of course we weren’t playing netball

"So, you don’t think I’m sick, then?" I asked Sue, the next time I caught up with her at university. I was anxious that she might have changed her mind in the meantime. "You are still happy being friends?"

"Of course I’m happy being friends. But you’re the first lesbian I’ve ever known. How does it work, exactly? Do you just . . . sort of . . . fancy women?"

"Um, yes, I guess that covers it. I’m not really the best person to ask, having only slept with my husband. I don’t think that qualifies me as any expert on lesbianism."

"Seriously? You mean to say you’ve only ever slept with your husband and nobody else? No uncontrolled urges that led to bed? Didn’t you at least . . . you know . . . try it out before you got married?"

"No," I said. "I know it makes me look like a dinosaur, and my friends did think I was a bit odd—"

"They’d be right there," Sue cut in, "I mean, weren’t you ever . . . you know . . . carried away by your hormones?"

"No." This line of enquiry was almost a welcome relief. Suddenly it was not my sexuality but my libido that was under the microscope.

There was no bell to signal the beginning of lectures at Canterbury University, but, like a herd of cows waiting for milking, the assembled students began flooding into the lecture theatre and I was saved any further scrutiny.

The year roared on. With university during the day, shift work at night, and two young children to taxi around to primary school, kindergarten, violin lessons and karate, I had almost no spare time. I went to the occasional bar, but even this got less frequent as exams loomed and study became more important. I finished my last exam with a sigh of relief.

I guess it was inevitable that once the term ended I might have to face a few things. Over the months since my confession, Sue had become more and more of a confidante. For years I had managed to find someone special to confide in. It was only ever platonic, but there was always a woman on my psychological radar. Sue had declared herself heterosexual as had most of my women friends. This time, though, I was determined not to get caught up in that frustrating web of unrequited love.

So, as the warm early summer weather settled and the days lengthened, I resumed my habit of having a drink at the bar after work on a Friday. Not every week and not with much peace of mind. I felt guilty because I was leaving Richard at home with the children, and also because of the contempt. When the lesbians at the bar discovered I was married and still living with my husband, there was a lot of pressure for me to ‘come out’. My ideal community, the haven for my bleeding soul, was a lot of hard work. The struggle inside went on, and, if anything, it escalated — and the only person I felt I could discuss it with was Sue.

We went on long walks together. Walks where we never stopped talking. When we had discussed a problem, it gave me peace of mind. Spending time with Sue was like plunging into a cool pool after a hot, turbulent day. She was the balm that took away the burn. But I’m not sure I had worked that out then. I just knew I felt better when she was around.

Our most adventurous walk was a hike from the Sign of the Takahe (which is an incongruous medieval-style castle) to the old staging post and now a café called the Sign of the Kiwi, at the summit of the volcanic cone which stretches out to become Banks Peninsula. The route we took went up through Victoria Park, then out of the park following a narrow track above the road that wended its way up to the summit. It was the beginning of a hot day. Dawn’s clouds had long since burned off and the sky was a breathless blue vault.

We had arranged to meet at the Sign of the Takahe, just after 10am. Although I was there first, I didn’t have to wait long until Sue pulled up in her Ford Telstar. This felt deliciously transgressive because up until now every second of my day had been committed. For the first time all year there was a gap: the children were at kindergarten and school; no essay to write; no exam to sit.

Sue looked gorgeous and fresh in her white t-shirt, long denim shorts and white leather trainers. We were elated to see each other, which did worry me because I was still adamant that I didn’t want to fall in love with a straight woman and endure any more heterosexual heartache.

As we climbed out of the fringe of houses around the lower reaches of the Port Hills we talked about our lives. I told her about the pressure I was under at the bar to ‘come out’, and my deep, unfathomable fears over what would happen if I did; and she told me about her marriage. We had talked about it before, especially about the difficulties she was having, and the amount of time she was left at home on her own. Sue’s marriage seemed less ideal than I had imagined.

I didn’t see this as an opportunity, but more as if we were kindred spirits in limbo. Not comfortable with where we were, but unable to move on. We were tied by history and commitment to our husbands and the love we felt for our children. The issues were complex, and we were lost in them like two people in a desert who discover their own footprints and realise they have walked in a circle, without finding the way out. But it was pleasurable, and we were unperturbed because our friendship was about the journey.

Until I made one fatal mistake. I patted Sue’s bottom the way I’d seen sportswomen do on the netball court, but of course we weren’t playing netball. I regretted it as soon as I did it, and started to agonise. What would she think: that I was some sleaze trying to exploit the loneliness of a remote path? If I could have cut my hand off at that point I would have. Mortified, I waited to see if she would react. Nothing. Thank goodness. Either she had genuinely not noticed, or she was prepared to let my Freudian slip go unchallenged. For the rest of the walk to the summit I flagellated myself. I deserved a straitjacket. At least that would stop me from ever making the same mistake again.

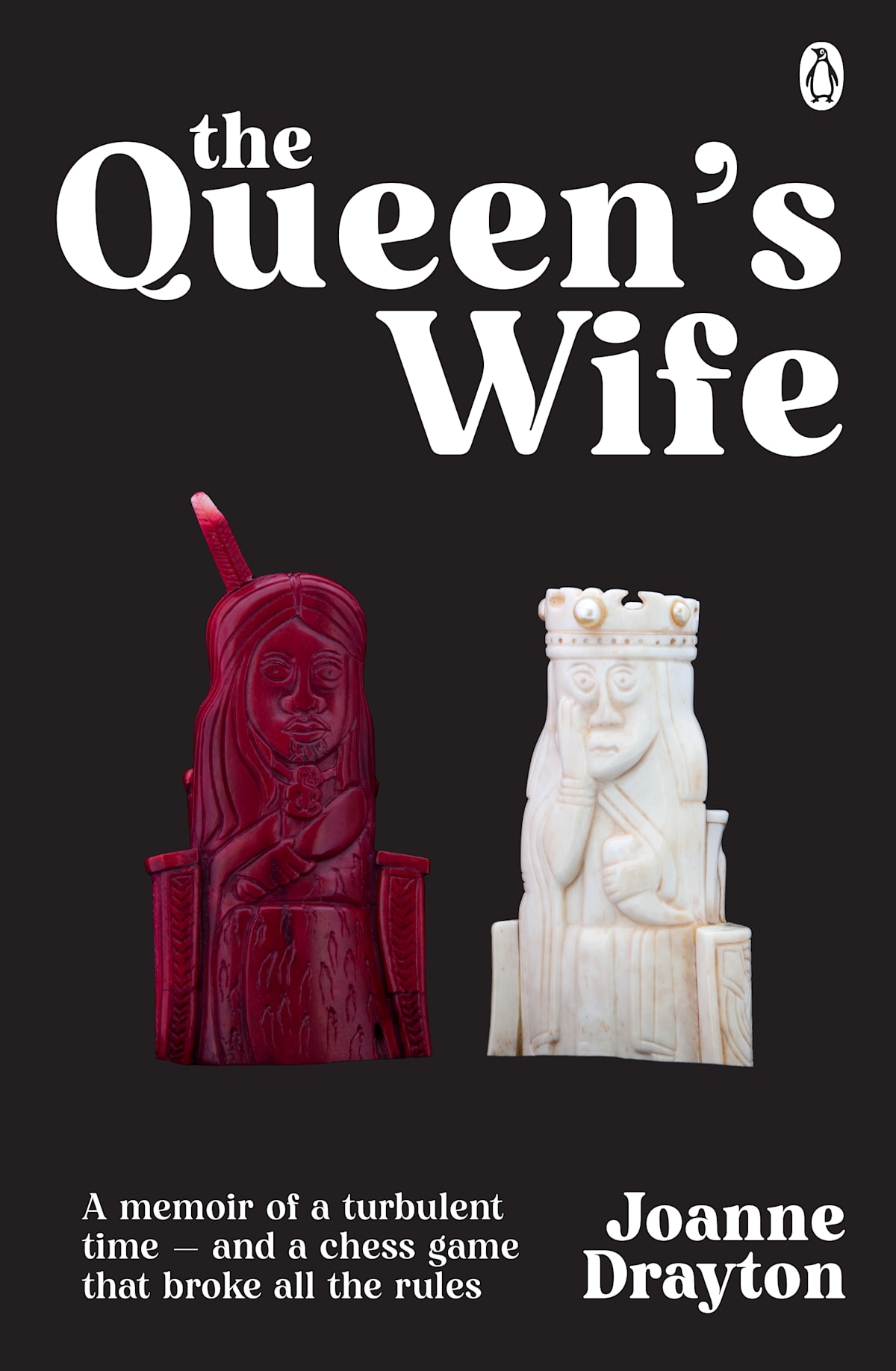

Taken with kind permission of the author from the new memoir The Queen’s Wife by Joanne Drayton (Penguin, $40), available in bookstores nationwide.