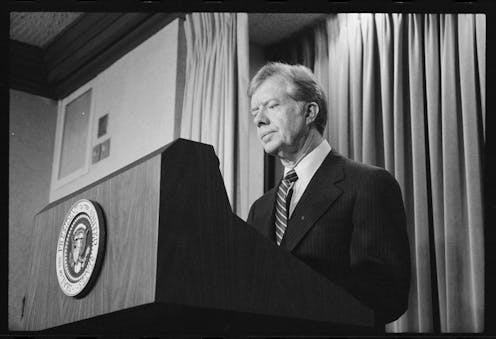

When historians and pundits praise Jimmy Carter’s achievements as the US president and extol his exemplary post-presidential years, they mention the recognition of China, the Panama Canal Treaties and the Camp David Accords. Almost no one mentions what Carter achieved in Africa during his presidency. This is a serious oversight.

When I interviewed President Carter in 2002, he told me:

I spent more effort and worry on Rhodesia than I did on the Middle East.

The archival record supports the former president’s claim. Reams of documents detail Carter’s sustained and deep focus during his presidency on ending white rule in Rhodesia, and helping to bring about the independence of Zimbabwe.

There were several reasons for Carter’s focus on southern Africa. First, realpolitik. Southern Africa was the hottest theatre of the Cold War when Carter took office in January 1977. A year earlier, Fidel Castro had sent 36,000 Cuban troops to Angola to protect the leftist MPLA from a South African invasion backed by the Gerald Ford administration. The Cubans remained in Angola until 1991 .

Mozambique was no longer governed by America’s NATO ally, Portugal, but instead by the left-leaning Frelimo . Apartheid South Africa – so recently a stable, pro-American outpost far from the Cold War – suddenly faced the prospect of being surrounded by hostile black-ruled states.

The unfolding events in southern Africa riveted Washington’s attention on Rhodesia, where the insurgency against the white minority government of Ian Smith was escalating. One week after the Carter administration took office it assessed the crisis in Rhodesia:

This situation contains the seeds of another Angola … If the breakdown of talks means intensified warfare, Soviet/Cuban influence is bound to increase.

The administration knew that if the war did not end, the Cuban troops might cross the continent to help the rebels.

And then what?

It was unthinkable that the Carter administration, with its stress on human rights, would intervene in Rhodesia to support the racist government of Ian Smith. But, given the Cold War, it was equally unthinkable that it would stand aside passively enabling another Soviet-backed Cuban victory in Africa. Therefore, the administration’s first Presidential Review Memorandum on southern Africa, written immediately after Carter took office, announced:

In terms of urgency, the Rhodesian problem is highest priority.

The Carter administration assembled a high-powered negotiating team, led by UN Ambassador Andrew Young and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, to coordinate with the British and hammer out a settlement. These negotiations, spearheaded by the Americans, led to the Lancaster House talks in Britain, and the free elections in 1980 and black majority rule in an independent in Zimbabwe.

There was another reason for Carter’s interest in southern Africa: race. Carter grew up in the segregated South of the 1920s and 1930s. As a child, he did not question the racist strictures of the Jim Crow South, but as he matured, served in the US Navy and was elected governor of Georgia, his worldview evolved.

He appreciated how the civil rights movement had helped liberate the US South from its regressive past, and he regretted that he had not been an active participant in the movement. When I asked Carter why he had expended so much effort on Rhodesia, part of his explanation was:

I felt a sense of responsibility and some degree of guilt that we had spent an entire century after the Civil War still persecuting blacks, and to me the situation in Africa was inseparable from the fact of deprivation or persecution or oppression of Black people in the South.

Parallels with the US South

Carter’s belief that there were parallels between the freedom struggles in the US South and in southern Africa may have been naïve, but it was important.

Influenced by Andrew Young, who had been a close aide to Martin Luther King , Carter transcended the knee-jerk anticommunist reaction of previous American presidents to the members of the Patriotic Front, the loose alliance of insurgents fighting the regime of Ian Smith.

Young challenged the Manichaean tropes of the Cold War. He explained in 1977:

Communism has never been a threat to me … Racism has always been a threat – and that has been the enemy of all of my life.

Young helped Carter see the Patriotic Front, albeit leftist guerrillas supported by Cuba and the Soviet Union, as freedom fighters. Therefore, unlike the Gerald Ford administration which had shunned the Front and tried to settle the conflict through negotiations with the white leaders of Rhodesia and South Africa, Carter considered the Front the key players. He brought them to the fore of the negotiations. This was extraordinarily rare in the annals of US diplomacy during the Cold War.

Carter has not received the credit his administration deserves for the Zimbabwe settlement. It was a success not only in moral terms, enabling free elections in an independent country. It also precluded a repetition of the Cuban intervention in Angola. It was Carter’s signal achievement in sub-Saharan Africa.

Angola and the Cold War reflexes

Carter also improved US relations with the continent as a whole. He increased trade, diplomatic contacts and, simply, treated Black Africa with respect.

During the war in the Horn of Africa, he resisted intense pressure to throw full US support behind the Somalis when the Somali government waged a war of aggression against leftist Ethiopia. His administration attempted valiantly to negotiate a settlement in Namibia and condemned apartheid in South Africa.

But in Angola, as historian Piero Gleijeses’ superb research has shown, Carter reverted to Cold War reflexes. He asserted that the US would restore full relations with Angola only after the Cuban troops had departed. This, even though he knew that the Cubans were there by invitation of the Angolan government, and were essential to hold the South Africans at bay. Carter’s was the typical response of US governments to any perceived communist threat. But it serves to highlight – by contrast – how unusual was the administration’s policy of embracing the Patriotic Front in Zimbabwe.

For the next 40 years, Carter focused more on sub-Saharan Africa than on any other region of the world. The Carter Center’s almost total eradication of Guinea worm has saved an estimated 80 million Africans from this devastating disease. Its election monitoring throughout the continent, and its conflict resolution programmes, have bolstered democracy.

Carter’s work in Africa, and especially in Zimbabwe, forms a significant and underappreciated part of his impressive legacy.

Nancy Mitchell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.