One of the most memorable images of retired Chinese supreme leader Jiang Zemin, who has died aged 96, was of his dramatic re-appearance during celebrations to mark the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2009.

As the tanks and rocket launchers rolled past Chang’an Avenue, Jiang’s face behind his trademark thick-framed glasses was a mask of defiance. His dogged ability to battle his way into favour and hold on to influence within the old guard at the top of the party very much characterised the trajectory of his political career.

Jiang played a prominent role in the celebrations, even though it was presumed he had been finally cast into the political wilderness after he held on to various positions of power, including head of the army, which complicated President Hu Jintao’s ascent to the pinnacle of power in the Communist Party.

Born in the city of Yangzhou, in Jiangsu province, he studied in Nanjing, then graduated from the electrical engineering department of Jiaotong University in Shanghai before transferring as a trainee in the Stalin Automobile Works in Moscow in 1955. He then served his time in the First Automobile Works in Changchun, one of the giants of China’s engineering sector.

Jiang’s wife Wang Yeping also comes from Yangzhou, and they have two sons, Jiang Mianheng and Jiang Miankang.

Well-known for his ability to successfully outflank his rivals, he proved adept at imposing himself on the bureaucracy and worked his way up to become minister of electronic industries in 1983 and a full member of the all-powerful nine-man Politburo in 1987.

In 1985 he became mayor of Shanghai and head of the party there, and it was from here that he was chosen by then-supreme leader Deng Xiaoping as a replacement for reformer party boss Zhao Ziyang, ousted for sympathising with the democracy movement crushed by the army in Beijing in June of that year, and prompting an internal power struggle that nearly tore the party apart.

He always said that the Tiananmen Square crackdown was essential to maintain stability in China, but at the same time, the fact that dissent in Shanghai on his watch had been dealt with without bloodshed meant he was a less controversial figure than other senior party figures.

He was expected to be a transitional figure, a safe pair of hands as the party steered its way along a path of economic reform, but he showed remarkable political nous and held on to power for 12 years and continued to wield influence as chair of the powerful Central Military Commission for several years after he had been expected to cede it to Hu.

Under Jiang’s tutelage, China had its longest period of stable economic growth under Communist rule, entered the World Trade Organisation and won the right to host the 2008 Olympics.

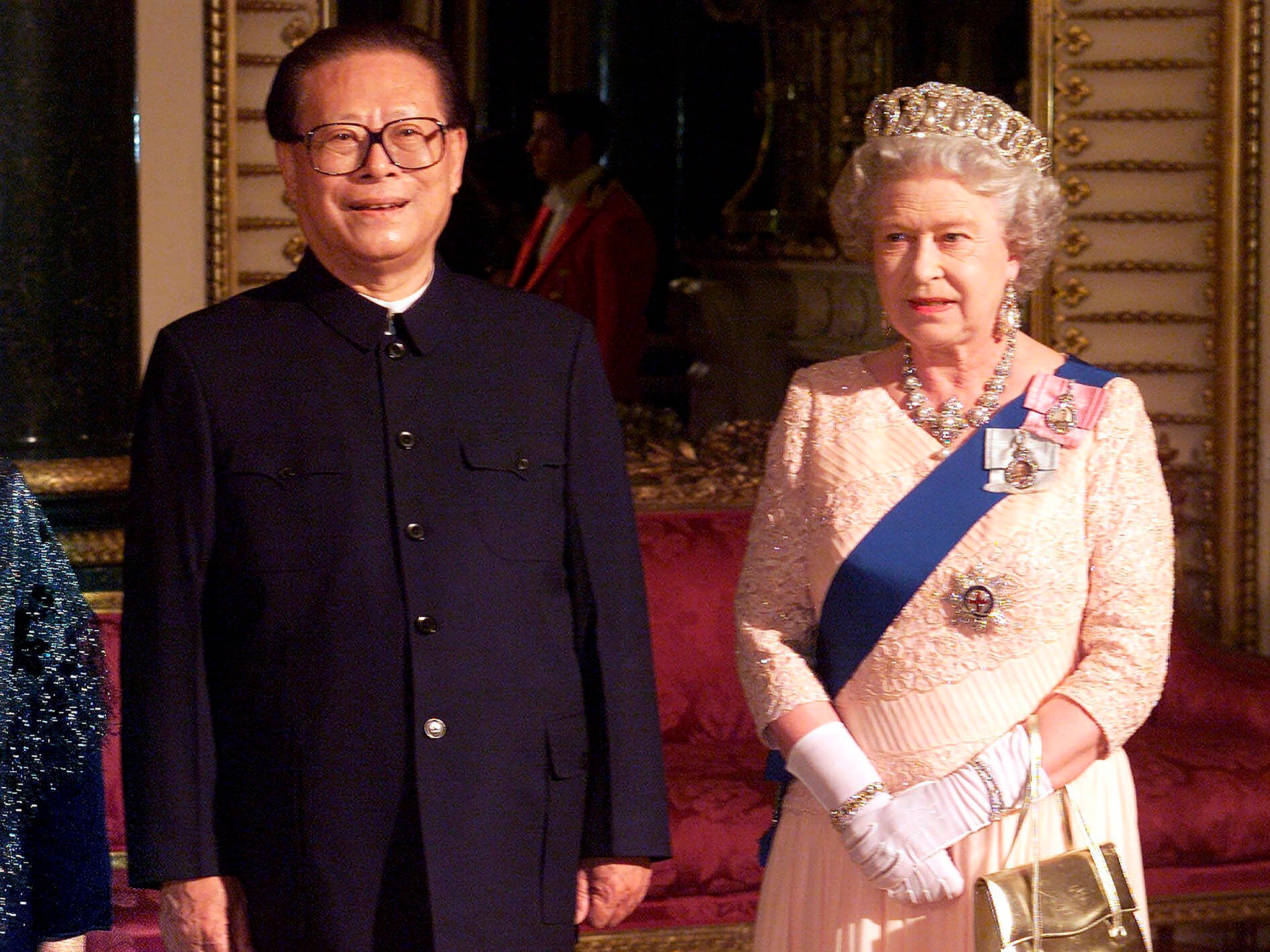

He marshalled the peaceful handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China, as well as that of Macau from Portugal, but kept up the party’s firm line on not tolerating any talk of Taiwanese independence. Jiang also orchestrated the crackdown on the Falun Gong spiritual movement.

While no one could ever have called Jiang a liberal, he did stand out as a modernising element within the Party structure, particularly on economic matters. He was instrumental in reforming China’s giant state-owned enterprises.

Jiang’s “Three Represents” political theory, which effectively provides a framework to allow capitalism a place within the Marxist-Leninist Party ideology, has been written into the party constitution alongside the hallowed Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory, securing Jiang a place in China’s socialist pantheon. Legacy is a big factor with former leaders – the current leadership is trying to cement its own legacy.

At a National Party Congress nine years ago, he positioned a grouping of his close allies into the Politburo, which meant his influence remained strong after he was supposed to have stepped down.

Many commentators have remarked how the engineer lacked the charisma of the Great Helmsman Mao Zedong or economic reformer Deng Xiaoping, but compared with the blue-suited leaders Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, who carefully nurture images of functional technocracy, he was quite a personality.

He was also clever at giving himself plenty of profile abroad, and he seemed to particularly enjoy his trips to Europe and America. During his time in power, he fostered ties with the United States, but he was not averse to a bit of populist sabre-rattling, such as during the time a US spy plane was forced to make an emergency landing in China after colliding with a Chinese fighter jet sent to intercept it, and during the furore following the Nato bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade.

Always fond of things American, ringing the bell at the New York Stock Exchange, and giving a speech at Harvard University, Jiang reportedly knew the Gettysburg address by heart and was fond of John Wayne. His rendition of Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender” at a meeting in Manila with then Philippines president Fidel Ramos is legendary. He also rode in a pick-up truck through President George W Bush’s Crawford Ranch.

A lover of literature, especially poetry, Jiang was musical, playing both the Chinese erhu, an instrument similar to the violin, and the piano.

However, once he stepped down from the leadership of the army, his power inevitably waned. His traditional power base was in Shanghai, and Jiang was believed to have suffered from the removal and prosecution for corruption of one of his allies in the so-called “Shanghai Clique”, Chen Liangyu, the former party boss of Shanghai in 2006.

As his last big public outing showed at the bombastic celebrations to mark the 60th anniversary of the Communist revolution, Jiang could still pull off the occasional power play.

He is survived by his wife and two sons.

Jiang Zemin, former president and Communist Party chief, born 17 August 1926, died 30 November 2022