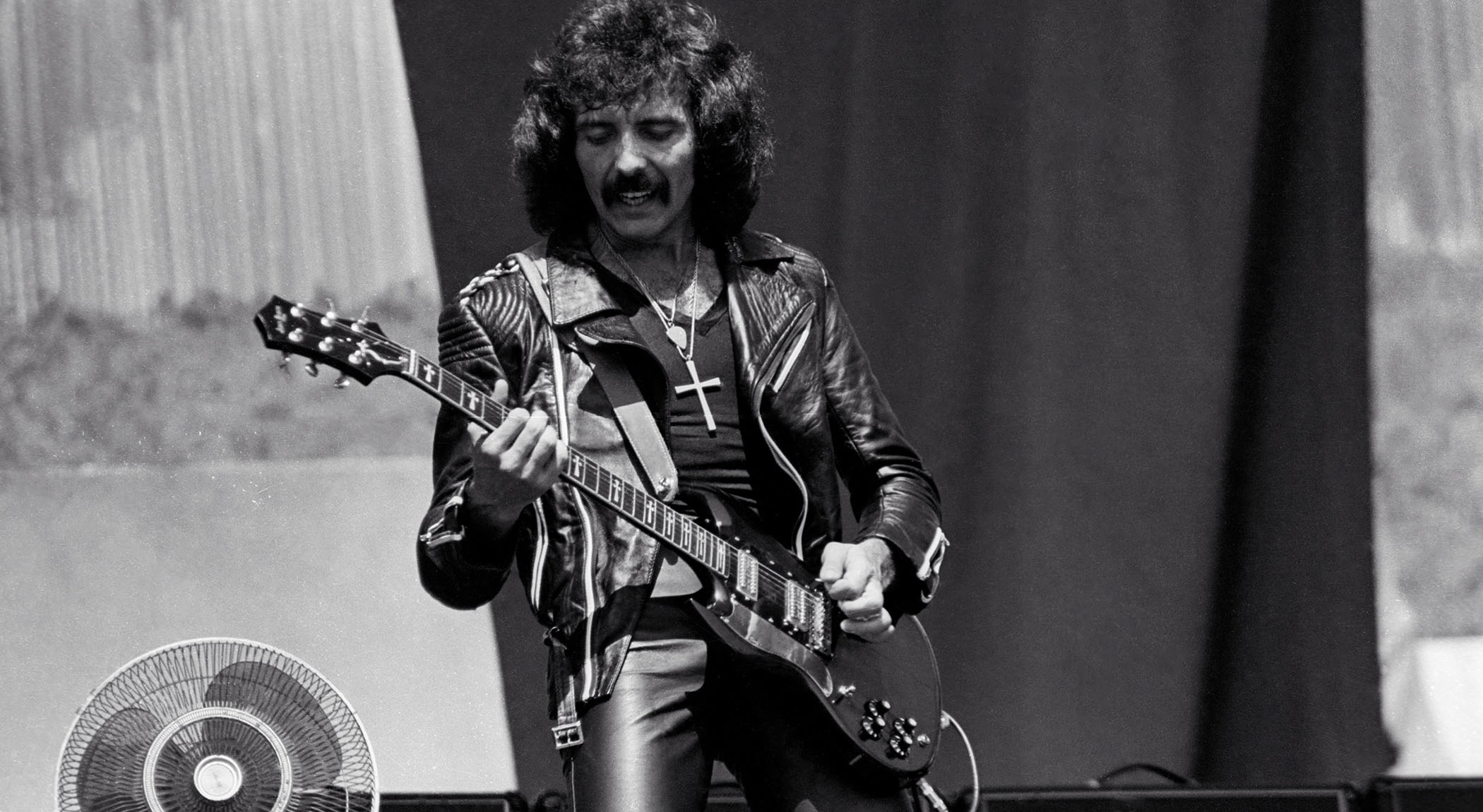

Iommi’s innovations in Black Sabbath would not only prove to be influential on the sound of the genre in its most classic form, but would also spawn many of its offshoots and subgenres, from the doomy discordance of the self-titled track that opened their debut to the groove-metal thunder heard on the chromatic riffs of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath and the proto thrash of Symptom of the Universe.

Then there’s the more progressive side of his playing, exquisitely documented by lesser-known deep cuts like Megalomania, Spiral Architect and The Writ, where the bold stream of consciousness seemed to laugh in the face of musical boundaries and choose to follow no calling but its own.

In that sense, his stature as the original and definitive metal riff lord often can feel like a double-edged sword; a well-intended acknowledgement doesn’t quite do justice to the wide breadth of his genius in full. To put it bluntly, Iommi’s influence on guitar playing and wider culture as a whole goes far beyond the obvious.

There’s a famous quote attributed to punk rock icon Henry Rollins: “You can only trust yourself and the first six Sabbath albums.” Some say the comment was made about the first four records (not the first six), but either way, there’s a comforting truth in such a notion.

The Ronnie James Dio-fronted years were mesmerizing in their own way, and there were certainly creative victories on later conquests with Tony Martin, and an honorable mention definitely goes to 13 – the 2013 Ozzy Osbourne comeback that would serve as their artistic farewell – though between 1970 and 1975, Black Sabbath were quite simply untouchable.

Iommi and his bandmates changed the face of music forever, to the point where even 56 years after their formation, you’d be hard pressed to find a heavy metal band that doesn’t owe them a colossal sense of debt.

The group called it a day in 2017 and are now spoken of in the past tense, though their fearless leader has soldiered on with ventures new. There’s been a slew of reissues spanning each and every era of the band, not to mention a photo book and his own aftershave line with Italian company Xerjoff, where fragrances have been promoted by the release of a new track. The latest offering, Deified, combines screaming wah-wah leads with gothic orchestration and medieval menace.

Given how it would so easily sit on the soundtrack for a horror movie, it’s very much business as usual for this metal master.

“Yeah, I agree, it would work nicely for a scary movie!” he says, talking to GW on a warm summer’s day from his home in Poole on the south coast of England.

“I do like that sort of stuff and always have. But I still feel like I’m experimenting and trying out new things. My approach to music has always been about venturing out a bit and pushing myself further.”

That concept of pushing himself further also can be attributed to the gear he’s used on these latest recordings, which includes the 2021 track Scent of Dark.

For someone who has built a career out of plugging Gibson SGs into Laney amps, it comes as a surprise to hear the metal innovator talking about digital gear – proving that it really doesn’t matter who you are, what you sound like or what generation you’re from; the quality of amp simulation in the modern age is something that just can’t be ignored.

“These latest songs were done in my studio,” he says. “I either used my Jaydee guitar or my main Gibson SG, possibly both. The guitars were going through my Kemper Profiler. I’ve also got a Laney plugged in over there, so it could have been a mixture of the two.

I do like being in a room with a head and cabinet, just to get that bounce back from the speakers. But as far as new gear goes, the Kemper has been working very well for me in the studio

“I have to say, I really like the Kemper. It was my producer Mike Exeter who introduced me to it a while back, and I was very impressed. Especially because you didn’t need to have all the speakers mic’d up; you could sit with it next to you in the control room.

“Mike sampled my Laney tone, and then we improved on that a little bit. I’ve found it to be very useful. And the sound quality is incredible; it can actually be quite hard to tell the difference between the Kemper and a real amp.

“Of course, I do like being in a room with a head and cabinet, just to get that bounce back from the speakers. But as far as new gear goes, the Kemper has been working very well for me in the studio.”

How’s the next solo album shaping up?

“There’s definitely something coming. When it will be here, I do not know. [Laughs] I won’t put Deified and Scent of Dark on the next album. Those are separate things for me. The tracks I’m working on right now are a mixture of styles from acoustic to heavy stuff. There’s a variety.

The Shadows were an instrumental band and I learned to play through their music

“I haven’t picked out exactly what I’m going to do with the songs or who I’m going to use or whatever yet, but I’ve recorded quite a few ideas. A lot of them have been done at home. The next thing we’re going to do is put some drums on, so it’s coming along.

“I’m just taking my time with it. I can only work on the new music on certain days because I’ve got other stuff on. I tend to work on a Monday and Tuesday with Mike Exeter. We’ll go in and focus on a particular track while also fiddling around with sounds and whatnot for other stuff.

“It’s been an interesting process, juggling lots of different ideas. My studio is at the house in [West Midlands village] Broadway. Here in Poole I don’t have a studio. We’re not down here enough to use one, really. We just come down for a few days and go back. Then I will pick things up at the beginning of the next week with Mike.”

Other than the Kemper, what’s the last piece of gear that impressed you?

“Mike gets sent things for me to try, as did Mike Clement – my old guitar tech [who passed away in 2022]. Things would get brought over and I’d say, ‘Oh yeah, I like that one.’ But most of these things are very similar. I must have hundreds and hundreds of pedals at home.

“I’ll try them and think they sound good but also realize they sound a lot like something else I’ve already got. Finding something unique is actually quite hard. There have been a couple that stood out, though. Anything I think is good gets to stay, and then there are boxes full of things that don’t stay.

“Mike Exeter brought me an octave pedal, the Electro-Harmonix Nano POG, a while back. It sounded really great, and we ended up putting it in my rack. I’m always open to trying things; I love doing that. Recently there was a guy from Mustard Effects who tried to copy my original booster and called it the War Pig pedal. I thought it sounded good.

“There was one pedal I got sent that did a ghosting effect, a bit like my old Laney amp. It was originally made by the cheap transformers and weird circuits in the heads, but this gadget – the Origin Effects RevivalDRIVE [overdrive] – recreates that effect really well. I’ve used it a bit here and there.”

Your last major public appearance was at the opening of the London Gibson Garage alongside Brian May and Jimmy Page earlier this year. You and Brian see each other a lot; what was it like reconnecting with Jimmy?

“I’ve seen Jimmy a few times over the years. We’ve gotten together here and there. He’s a really nice guy, I like him a lot. It’s fun to talk about what we’re doing, stuff that we’re working on – we’re both from the same era and still creating. We come from the same sort of stable. I don’t think either of us are into technical stuff; we stick to what we know, the things that work. The same goes for Brian.”

You’re all very multifaceted, mixing heavy riffs and aggressive blues with more psychedelic and acoustic influences. It made some headlines when you turned up together.

“It is great to hook up with each other. We don’t do it enough. Brian and I see each other all the time, but I don’t see Jimmy that much. When I do, we always have a great conversation and enjoy each other’s company. It’s rare to do that with the people from our generation because they’re all popping off. [Laughs] That can make it difficult.”

Let’s go back to the beginning. You were 17 when you lost two fretting-hand fingertips in a factory accident and got told you wouldn’t play again. That is undoubtedly every guitarist’s worst nightmare.

“Oh, it was awful. I just couldn’t believe it, particularly as it happened on the day I was going to leave the job, which is insane. I’d given my notice to leave so I could join a band and go to Germany. It was a good opportunity. I went in on the last day and that’s what happened. It shocked me. I never had any idea something like that was going to happen. I was truly devastated.”

And then somebody told you about Django Reinhardt, which must have felt like a ray of light given how much he accomplished after his injuries.

“It really felt like that. It was actually the foreman at the factory I worked at. He came over to see me afterwards. He knew I had the accident and also knew the machine was wobbly and faulty. I shouldn’t have been on it, really. So he came over with a Django record and said, ‘Have a listen to this.’

“I was down at the time and didn’t want to listen to anything, but he got me to put it on and I went, 'Yeah, it’s brilliant.' Then he told me the story [Reinhardt suffered extensive burns over half his body – including the ring and little fingers of his left hand – in late 1928], and I must admit it really did help and inspire me to work on a way to play with what I had left.”

You were briefly a member of Jethro Tull. What did you learn from them?

“That was a strange meeting. We did a gig with Jethro Tull and it was the night Mick Abrahams was either fired or left – I don’t know what happened there. I saw them passing notes to each other on stage and thought it was weird. After the show, they asked if I’d be interested in joining, which was really surprising.

“On the way home in the van, I said to the other guys, ‘Tull asked if I wanted to join them,’ and they all told me to go for it. Then I had to come down to London and audition, because there were so many guitar players interested. I walked in and saw all these musicians waiting in line and thought, ‘Oh no, forget it.’ But one of the crew saw me and told me to go and sit in a cafe across the road.

“They fetched me when everyone was gone. I played and they told me I’d got the job. It was quite a different thing for me. A big step in them days. It was a big deal for me to even get out of Birmingham. That’s how it all happened. And it certainly was a good experience for me, because I learned a lot about how they worked and how [founding frontman] Ian Anderson would run the band.”

And how was that, exactly?

“They would rehearse at a strict time every morning at nine o’ clock or whatever it was and then break for lunch. It was a bit like going to work, really. In Black Sabbath, we never did that. We’d get together whenever, probably after midday. Those early morning starts were a bit of a shock. It was good to learn about how other people work.

“If you want a career in music, you’ve got to take it seriously. That’s what I spoke to my guys about. After a couple of things with Tull, including The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, I left and said to the Sabbath guys, ‘Let’s get back together – but we’ve got to work at it and put everything we’ve got into it.’ They agreed.”

You’ve said Hank Marvin and Eric Clapton were your main influences early on. Was there anyone else?

“I might have picked up other influences, but I didn’t tend to realize them. As you say, Hank Marvin was the original one, but his playing was worlds apart from what I would go on to do. That was the start for me, though. The Shadows were an instrumental band and I learned to play through their music.

“Then I went from there to Eric Clapton’s take on the blues and the John Mayall stuff, all of which I really liked. It kickstarted a whole genre of heavy blues players. Mayall put forward a lot of guitar legends, from Peter Green to Clapton to Mick Taylor.

“After that, I never thought much about influences. You get into the habit of doing it yourself. Everybody starts off by copying their favorite players and learning from them, and then you do your own thing and venture out. Well, some people. Others are happy copying things perfectly and exactly, because that’s what feels good for them.”

Jeff Beck was another one of the early British blues heroes. Were you a fan of his work?

“Oh yeah, Jeff was great. I met Jeff early on because we had the same manager. He was so different and unique. A truly great player who was just doing his own thing that was 100 percent him. It’s true what they said; nobody could play quite like Jeff.”

I didn’t know anything about the last note being a tritone. I didn’t know what the term even represented, though I knew I liked the sound of it

Black Sabbath was born out of your fascination with the macabre. Much of its eeriness stems from that tritone interval. When did you first become aware of tritones – and how did you come up with that riff?

“I’ve always been interested in horror films and that type of music. I’m into anything dramatic. We went into rehearsal one day, and Geezer [Butler, bass] was just playing around doing some [English classical composer] Gustav Holst stuff on his bass. I came up with this riff made out of three notes, the second being the same as the first but an octave up.

“But I didn’t know anything about the last note being a tritone. I didn’t know what the term even represented, though I knew I liked the sound of it and the feel we got from it. The mood was like what you’d experience watching a horror film. That’s what I related it to while putting the song together.”

The faster palm-muted riff toward the end is built off the Aeolian scale. How much were you aware of the modes at this point?

“I knew nothing about the modes. I never read music and don’t know anything about that side of it. For me, it’s all about feel and what I come up with at the time. When we did that section, just like everything I’ve ever done, I started playing something and thought, ‘Oh, I like that.’ If I like what I hear, I use it, and if I don’t like it, I won’t. That’s how Black Sabbath came about.

“I knew I wanted the end section to lift up into this galloping idea. I like tempo changes and felt it needed to go somewhere else. For some reason, that’s something that’s just embedded in me. One riff will take me so far, and then I will think about going into a chorus or another riff. It’s what I’ve been doing the whole time.”

That galloping rhythm is associated with a lot of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal bands that followed.

“Yeah! I can hear how the up-tempo stuff like the end of Black Sabbath and Children of the Grave affected what came next. It’s almost like this throbbing sort of rhythm.

When the Strat went, I couldn’t bloody well believe it. I’d worked on that guitar myself for a long time, getting the fretboard right, the frets down and the feel just how I like it

“A lot of the bands that came after ended up looking up to Sabbath as an influence, because there were very few of us doing that in those early days. It was just Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and ourselves. The heavy groups that came after went back to the three of us and learned things.”

Sleeping Village doesn’t get talked about enough. From the nylon-string intro to the meaty Dorian blues riffs and up-tempo layered solos, it’s very experimental – despite your all being very young at the time.

“I like mixing different moods and styles. If you have a heavy song, it makes sense to have a bit of a rest and go into something more laid-back, like Sleeping Village or whatever. And then go back into something heavy again, just to give it a bit of light and shade. It’s more interesting than having an album stay heavy the whole way through.

“I like to mix these elements on the albums but also within actual songs, like Sleeping Village or Die Young, where we drop down to a quieter part. It’s an important part of the way I write.”

From what you’ve told us in the past, that first album was made with your backup SG into a Laney LA100BL and a Dallas Arbiter Rangemaster boost. But Wicked World was recorded with your Strat, which had a pickup failure during the sessions.

When the Strat pickup went, I had to pick up the SG. From that day on, I never looked back

“That’s correct. When the Strat went, I couldn’t bloody well believe it. I’d worked on that guitar myself for a long time, getting the fretboard right, the frets down and the feel just how I like it. I needed to do all of that because of my accident. So we went in to make our first album and the guitar pickup went right at the beginning of the process.”

“In those days, it was a big fiasco getting a pickup changed or fixed. It wasn’t like how it is now, where you can go into any guitar shop and someone will be able to swap it. Not only that; we only had two days to make the album, one of which was for recording. I had to use my SG, which was the backup I kept on the side.

“I hadn’t owned it long, so I’d never really used it. When the Strat pickup went, I had to pick up the SG. From that day on, I never looked back. I stuck with the SGs. But at the time, I’d only used my Strat in combination with my booster and the Laney. That’s what I’d been using to create my sound, so it was quite scary having to improvise with something else.”

As you say, you ended up sticking with SGs for your entire career. Why that instead of, say, a Les Paul?

“I’ve always felt the SG is a comfortable guitar to hold. I really like the look of a Les Paul, but with my injuries from the accident, I always felt I couldn’t get up to the top frets, almost like my fingers weren’t long enough.

“It didn’t feel as comfortable as the SG and it’s very important as a player to feel comfortable. I did have a Les Paul later on but I never played it much. They look great and I love the sound other people have gotten with their Les Pauls, but the SG seemed to suit me best, so I stuck with it.”

Have you ever been tempted to try out an ES-335, a Telecaster or maybe even a superstrat?

“I think I tried a 335 at some point. But the problem was you couldn’t get left-handed ones. I had to get a regular one and turn it upside down, playing it that way. But I never used them much. It was always back to the SG.

“The only other guitar I really liked was that original Strat, which I wish I’d kept. I can’t believe I got rid of it. This was before I knew you could easily change pickups and things. I just thought the guitar had completely had it, so it was time to get rid of it. A big mistake.”

How many guitars do you own in total, and which would you say are the most collectable?

“I don’t really know, but the figure is probably around 70. I’ve gotten rid of quite a few. Some have gone to the Hard Rock Cafe and places like that, or auctions that are raising money for charity. So in terms of what’s left, it’s probably around 70 or 80. I only use so many, to be honest.

“You can have all these guitars but you don’t use them. Some might get pulled out now and again, but I tend to stick to about three or four that I use all the time. That’s the Gibson SG, which is a replica of my original, and the Jaydees, which were great instruments built by John Diggins. He’s passed on now, but he made me a guitar just before that happened, which was a great honor. I have the last guitar he ever made.”

The Monkey Gibson SG is probably the guitar you’re most associated with. Is that still with the Hard Rock Cafe?

“Yeah. I did try and get it back, to be honest. The guy who used to buy memorabilia for the Hard Rock came to England and visited me. He wanted to buy some stuff and I said it should be fine.

“I’d retired the Monkey SG because it was too valuable to me; I didn’t want to take it on the road and risk it getting damaged. He offered to buy it and it seemed like a good idea because the guitar could be displayed for people to see and kept safe, instead of sitting in a case somewhere in my storage.”

“But the deal was if I ever wanted it back, I could let him know and buy it back for the same price. It seemed fair enough, a good deal. Anyway, he passed away, so that was it. We tried to get in touch with Hard Rock to get it back and they knew nothing about the deal. But they allowed Gibson to go in and take the guitar in order to copy it exactly.

“They made the replicas; I think we did about 50 of them and I own two of those. I have to say they are exactly like that one I owned and they are what I use in the studio. They have the same knocks and bumps as the original, plus the little monkey sticker. It’s the same guitar, basically.”

The second album is loaded with hits. Even the lesser-known cuts like Hand of Doom and Electric Funeral are firm fan favorites. What are you most proud of from that album?

“It’s hard to pinpoint because I don’t really think like that. Certainly, as far as riffs are concerned, there’s a lot to like about Iron Man. I’m proud of how all the different changes piece together in that song. To be honest, I’m very proud of Paranoid as a whole. There are a lot of good tracks on that.”

As we carried on playing it live over the years, Iron Man got slower and slower, just to give it more depth and power. That’s what you do as a live band

The Iron Man riff uses power chords built off the natural minor scale. But perhaps the real magic lies in the drag of the tempo you chose to play it in. Maybe it wouldn’t have had the same effect sped up.

“Funnily enough, when we used to play live, we’d slow it down even more. When we went into the studio to do that album, we were so hyped up we were actually playing it a little faster. Then you end up sticking to that tempo because that’s what everyone hears on the album.

“But as we carried on playing it live over the years, it got slower and slower, just to give it more depth and power. That’s what you do as a live band. And other songs would end up being faster when we played live. Bill [Ward, drums] would get carried away with the tempo – or I would.”

The E Dorian runs in Planet Caravan are responsible for getting a lot of metalheads into jazz. How did you go about attacking that one, and what influences were you thinking of?

”I’ve always listened to jazz and would say Joe Pass was one of my favorite players from that style. There’s some blues stuff in the mix too. I was listening to the chord movement and thinking to myself, ‘What does this need and what leads would fit best?’ And I’d still happily play in a jazzy style now if the song calls for it.

“I’ve always liked jazz. In fact, for some of the live shows in the past we used to do a bit of a jazzy bit. Bill really loved jazz drumming, so we’d incorporated some of that into our show. Even the debut album, Wicked World had a lot of jazz going on.”

You’ve mainly stuck with the boost and wah pedal over the years, but the Paranoid solo famously features a ring modulator effect.

“I remember trying it out and thinking, ‘Oh, that could work here!’ It’s so easy to fall into the trap of not experimenting. It’s nice to try things out and surprise yourself. If it works, I keep it.”

It’s so easy to fall into the trap of not experimenting. It’s nice to try things out and surprise yourself. If it works, I keep it

Early songs like Iron Man, N.I.B. and Fairies Wear Boots have these really melodic vocal-like guitar leads higher up the neck.

“I like that stuff because I don’t see myself as a technically great player. I prefer to focus on the feel. All these amazing guitar players today, I think they’re great, but I couldn’t do what they do. It’s just not my style. I like to improvise and feel it. What I play might not be technically that hard, but it’s the sound I’m going for.”

Who was the last guitarist that impressed you on a technical level?

“The first one was Eddie Van Halen. When they toured with us early on in their career, I thought he was really good and had come up with something very different for its time. Nowadays you can see how all the technical players have learned from Eddie. The funny thing about him was, much like me, he didn’t read music or anything. It was all from feel. He was inventing stuff just using his ears.

“Some of the guitar playing I hear these days is too technical. You have to be precise on this note or that note. I can’t do that – if I do a solo on a record, it’s never the same live. I can’t reproduce what I did in the studio. I’ll do something similar but not exact.”

The respect was mutual. Eddie once said heavy metal wouldn’t exist without you. It must’ve been incredible to see him so early on in his career, witnessing the changing of the guard first-hand.

“He was great. We became really close friends on that tour, because we went out for eight months or something like that. He used to come round to my room in the hotel, because we’d often be staying at the same one, and we’d stay up for hours talking.

“It was lovely, and we stayed friends through the years until he passed. He was a great friend, such a nice guy who did so much for us guitar players. I really liked Eddie.”

Eddie used to come round to my room in the hotel, because we’d often be staying at the same one, and we’d stay up for hours talking

Did you ever get to jam together?

“Yes, we did. Van Halen came over to play in England, so he got in touch with me. He was in Birmingham and wanted to meet, but we were rehearsing that day so I didn’t think we’d get together. Then I suggested he came to rehearsal and he said he’d love to. So that’s what he did.

“I picked him up at the hotel and we went by the guitar shop so he could bring one along and have a play. It was good. The other guys couldn’t believe it – at the time it was the [Cross Purposes, 1994] lineup with Tony Martin, Bobby Rondinelli and Geezer. I turned up with Eddie and they were like, ‘What’s going on?’ We all ended up having a play together and it was a lot of fun.”

Henry Rollins once described your tone on Master of Reality as like “hearing lava.” You started tuning down to C# to get more of a sludgy feel, which in turn gave birth to a whole movement of stoner and doom metal.

“It did! Again, it came out of experimentation. I’ve never gone by the book, thinking I have to do things a certain way. I always go with what I feel is right, and quite often that might involve stepping out of the regular thing I’m known to do. I’ve had such an ordeal with gear following my accident.

“I made up my own set of guitar strings because the regular sets were too heavy for me. So I got some banjo strings for the first and second, and then dropped the gauge down on a regular set in order to make it lighter for me. That way it wouldn’t be so hard for me to press down.”

“And then I went to companies asking if they could make me a light gauge set of strings, and they told me ‘Oh no, that will never sell – they won’t be good and they won’t work!’ And I argued, ‘Well, they do work – I use them!’

“Of course, years later, you’d have things like [Ernie Ball] Super Slinkys and all sorts of stuff. It’s peculiar, because when I first approached these companies in the early days, they really didn’t want to know. It’s been the same all round for me, even with guitars.”

How so?

“I went to a company years ago and asked if they could make me a 24-fret guitar and got told they wouldn’t because nobody would use it. That’s why I invested in John Birch’s company. He was from Birmingham and had done a couple of repairs for me. When I asked him about making a 24-fret guitar, he said, ‘Let’s have a go!’

“You have to jump out of the box and try stuff. I used that 24-fret guitar for years and then, of course, what happens? Later on guitar companies started making them. That’s what it’s all about, though. You have to come out of the box, experiment and try things.”

It’s funny you say that; it was around this period that you started introducing more acoustics and cleaner tracks like Embryo, Orchid and Solitude.

I never ever questioned what Geezer did because I know he’d always play the right thing. He always knew how to accompany me, it’s almost like he knows what I’m going to play before I play it

“People were telling me you can’t put an acoustic track on a Black Sabbath album. And I would say, ‘Why not?’ It’s like there was a law against it. The same people told me I couldn’t tune down on Master of Reality – but why? The reactions were very peculiar in those days. The only way to prove it was to do it, and then it would become acceptable later.”

After Forever encapsulates the fantastic chemistry shared between you and Geezer, especially when he plays up high.

“That’s the thing with myself and Geezer. We could always lock in together. It’s amazing how quickly he could pick onto stuff. I’d play him things and straight away he’d put something to it.

“I never ever questioned what Geezer did because I know he’d always play the right thing. He always knew how to accompany me, it’s almost like he knows what I’m going to play before I play it. I guess that came from us being together so long and creating that sound together.”

Wheels of Confusion kicks off Vol. 4 with some heavy blues that sounds like Eric Clapton on steroids – arguably some of the best tones you’ve ever recorded.

“It’s interesting – my rig never changed much. I’d always go in with my booster. To go back, I started off in the Sixties with this Rangemaster. I lived up in Carlisle with Bill, we’d joined a band up there [the Rest]. There was a guy who lived nearby that worked in electronics and he came up to me one day saying he could make my treble booster sound better.

“I said, ‘Oh, can you?’ and he told me to hand it over and he’d bring it back in a couple of days. So he took it away, brought it back and I really liked what he’d done and how it worked in combination with the guitar and amp. I used the same booster right up to the [1980] Heaven and Hell album.”

“Then there was a guy who came to work for me who used to do Ritchie Blackmore’s stuff. We’d ordered six Marshall amps, and he said he’d put an extra valve stage in them. We had a house in Miami back then and gave him his own room. He started rebuilding these amps for me and did a great job.

“One day I went in and asked, ‘Where’s my booster, by the way?’ and he said, ‘What booster?’ When I told him which box it was, he said he’d thrown it away ages ago. I couldn’t believe it and never saw that pedal again.

“Annoyingly, nobody ever saw what resistors or transistors or whatever else was in it, which means nobody has ever been able to reproduce it exactly for me, though we have tried. The guy who built it passed away. But I’ve stuck with the same concept for my gear since forever – the SG into a Laney via a booster.”

You chose to bring in a major third harmony to add color to the opening riff of Supernaut.

“I realized what might work well there just through trying stuff. You have to remember, some things don’t work out. But that one did, and it really added something to the riff.”

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath could be your heaviest riff of them all, using power chords that snake their way around the second, third and fourth frets.

“Before making that album, we went to L.A. to record and it never worked out. I got writer’s block and just couldn’t think of anything. I was a bit like, 'Oh, shit!' Then we came back to England and had a couple of weeks off. I’d never had a creative block like that before.

“I was really worried because I just couldn’t think of anything. So we decided to create a bit of atmosphere and hired Clearwell Castle. We set our gear up in the dungeons. Bloody hell, straight away the first riff I came up with was that one from Sabbath Bloody Sabbath.

“I knew I really liked the sound of it, and then we built it up from there. It ultimately comes down to the mood you’re in, where you are, the atmosphere there and what you can create. Being in the dungeons of a castle clearly had the right effect on me.”

The closing track on that album, Spiral Architect, is like a love letter to progressive rock in terms of how it builds from a reverberated acoustic into the full band against an orchestral score. How’d that one come together?

“It’s another example of us trying out different approaches. People used to say we couldn’t use orchestration in a band like Black Sabbath. But why not? Also in those days, the orchestras and classical musicians didn’t look on us favorably. They looked down on bands like us. To have some people [the Phantom Fiddlers] come and accompany us was great. The fact that they enjoyed it was even better.”

Don’t Start Too Late is a solo performance where you use an acoustic with loud repeats. Brian May, Nuno Bettencourt, Yngwie Malmsteen and Joe Bonamassa have done similar things with delay in the time since.

“There are definitely a lot of similarities between Brian May and myself. We’ve been very close since the Seventies. It’s funny, we’ve both been using the Rangemaster since early on. Mine were going into Laneys and his were into Vox AC30s. But it’s the same principle.”

“I used to rely on Brian a lot because I’d constantly have problems with people saying there was too much interference coming through my booster. And I’d have to explain, ‘I know, but that’s part of my sound!’ In them days, you’d pick up bloody taxis and everything. There was no isolation. Brian would back me up and say, ‘That’s the sound – don’t change it.’

“Sometimes you’d get some boffin come along telling me, ‘I can get rid of that for you,’ and I’d say, ‘Oh, can you?’ But it would always change the sound and I didn’t want my sound to change. The only person who understood how I felt in those days was Brian, because he had the same problem. We both had a bit of noise but were ultimately getting the sound we wanted.”

Symptom of the Universe would directly influence the thrash metal bands that arrived the following decade.

“And it was nice to hear those thrash bands paying tribute to us. It’s great how they were able to push it forward into something new and turn it into their own thing. I was just coming up with things I liked.

“So it was brilliant to hear about other musicians liking what I’d done, taking the same kind of idea and improving on it, evolving it into their own sound. Like Metallica, for instance, who probably learned things from us as well as other people.

“What they did with the metal sound, turning it into thrash, was fantastic. They’ve always been respectful toward us and they’re lovely guys. I love their attitude toward things, the way they write and everything. It reminds us a lot of how we were – everyone in one room rehearsing together and taking it seriously.”

The Writ and Megalomania are up there with the most leftfield tracks you’ve composed.

“I have no idea how I came up with ideas like that, but I agree. To be honest, I’m still doing it now. I’ve got hundreds of riffs at home. I’ll put something down and then move onto something else, start working on that and something else comes up. It’s always been that way. I seem to be able to come up with lots of riffs. It’s probably the only thing I can do!”

What kind of exercises helped you most on your guitar journey?

“There weren’t really any exercises. For me, the main thing was getting used to playing with thimbles. That was the difficult bit, that was the exercise, I guess, trying to move my fingers and hit the notes. And it’s probably why I ended up using a lot of trills. Early on, I couldn’t bend the strings that hard because it would hurt my fingers, so I came up with the idea of using trills. I do that a lot and it’s probably become a bit of a trademark.”

You are well-versed in the art of the blues. What’s the secret to playing with heart, soul and authority?

“I can only speak for my own playing, but I love the sound of blues because it’s from the heart. It’s about how you feel at that moment in time. Like I said earlier, I can’t read music or play the same thing twice. It’s all about how I feel right there and then, which is where the blues comes from, when you think about it.

“You have to believe in what you’re doing and play it like you mean it, as opposed to performing the fastest guitar solo in the world or something exactly note-for-note. The guitar should be a part of you. By doing it more and more, you learn from yourself. If I sat down now and watched a video of someone shredding, I’d probably turn it off. I can’t do that stuff, it’s not how I play.”

“I remember doing an instructional video years ago, one of the first ones when they started doing those things. I was in L.A., and they were asking me to play my solos from the records – but slower. It wasn’t natural for me. I can’t play the same solo; it would always be slightly different. If someone’s learning guitar, my best advice would be to use your ears and feel it in your heart.

“Sure, some people watch videos and copy things, and that’s great. The technical players these days are brilliant. Even really young kids in their bedrooms are doing incredible things. But I always go back to the roots of the blues, looking deep inside myself and telling the truth. I don’t think about what can impress people or break speed limits. The only thing that matters in my mind is how it sounds to me.”

One final question. Will we ever see Black Sabbath on stage again? Bill recently said he’d love to join you.

“Who knows? You can never say never, and we never have said never. It really depends on everybody’s health and what we’d expect from each other now. Can we still play and sound the same together? I don’t know because it’s been such a long time. It’s in the air.

“By the time it comes around, if it ever does, we’ll have to see what state everybody is in and whether we can climb on stage. If we did, it would have to be good otherwise I wouldn’t do it.

“There’s no point in just getting up, what can you prove by doing that? If it’s not right or as good as it was, then there’s no point in doing it. In my eyes, it has to be as good or better.