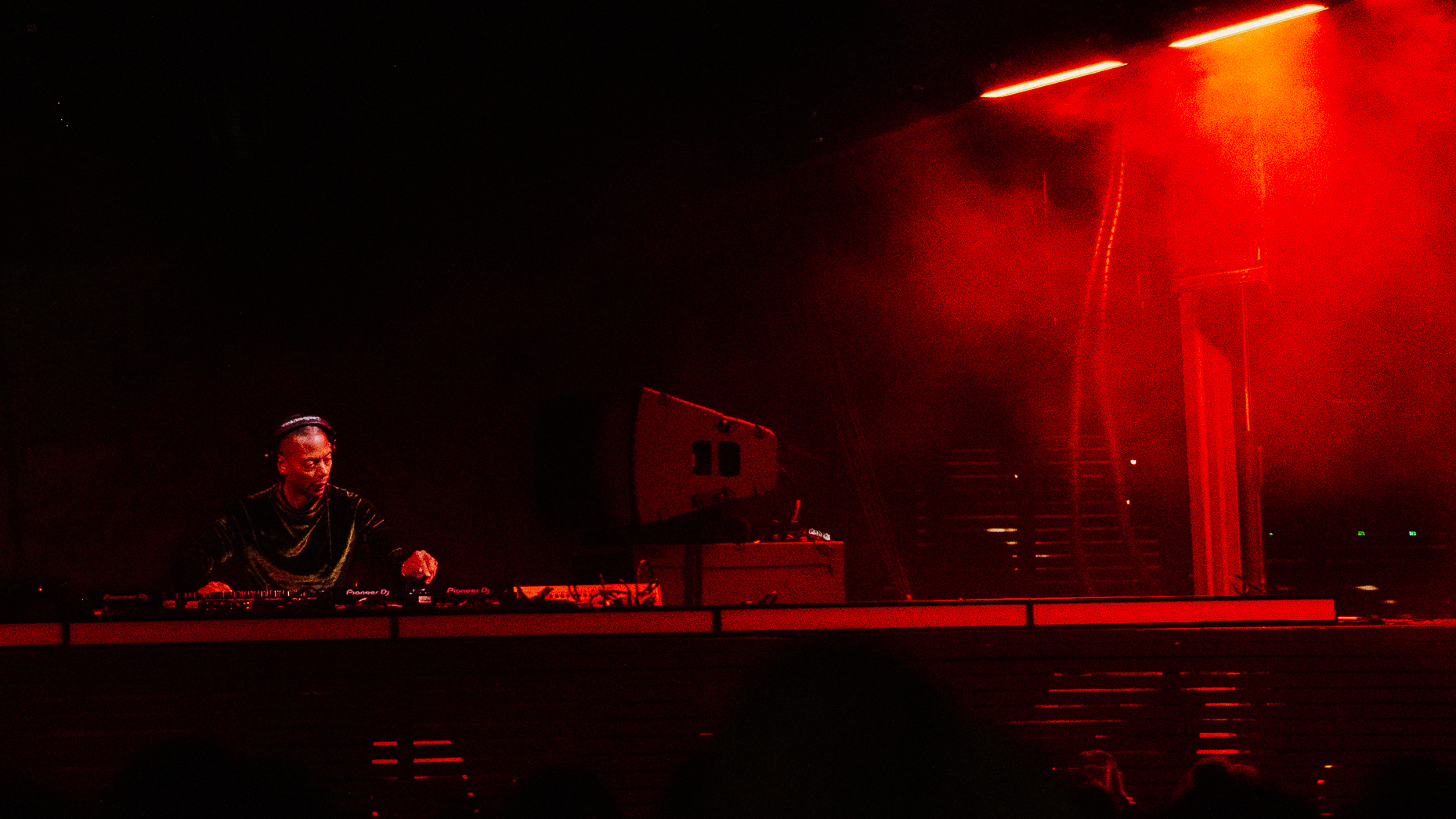

The word legend tends to get bandied about way too easily sometimes but there are among us certain artists for whom the description fits perfectly. Jeff Mills is one such artist.

From his pioneering work as part of electronic collective Underground Resistance in 80s Detroit and his early 90s establishment of his own Axis imprint, Mills has ploughed a unique and ever-evolving course through techno.

Always innovative and keen to push any and every envelope, Mills most recent incarnation is the 3-piece electro-jazz-afro-funk ensemble Tomorrow Comes the Harvest who blew hearts and minds at the CRSSD Festival.

One could wax lyrical ad infinitum about the contribution Mills has made to electronic dance music over his career; the DJ skills, the soundtrack work, the 909 workouts but why do that when we were offered an audience with the man himself. The one and only Jeff Mills.

For your 303 Day performance at CRSSD Festival are you flying solo or is the band appearing with you?

"I’m with the band, with two other musicians and we’re currently still on a tour that started last summer, and these are some of the last dates of this segment of the tour. It’s quite interesting because we’ve worked out all the kinks and unclear parts and everything is much more defined, and we really have a clear objective for the performance."

Over the years, you’ve worked with lots of musicians is that a way of keeping challenging yourself, musically?

"Many moons ago, just before Underground Resistance, I was in a band called Final Cut, which was an industrial-dance thing with four musicians. So, I learned about music from playing, collaborating and creating with other musicians. Then with Underground Resistance we literally made everything together… we found a really fluid way to produce a lot of music in a very short period of time.

With Underground Resistance we literally made everything together… we found a really fluid way to produce a lot of music in a very short period of time

"Playing with other musicians is actually more of my career than playing as a solo artist. Playing with orchestras and working with other musicians is really a large part for me. Sometimes it’s difficult to get there by yourself - obviously the other side of the coin being that, when you’re working by yourself then there’s no compromise at all.

"But when you are with someone who understands what the plan is and what the objective is then you can do some incredible things. So, that’s always been the case, and with Tomorrow Comes the Harvest it’s even more so the case."

Why is that?

"Well, we’re only really thinking about the objective and not so concerned about how we actually get there. Individually, we know what the objective is so we’re collaborating and helping one another to get there. It makes dealing with music much more valuable. When you can clearly see what the result is from your actions and there’s a clear goal what the music is actually supposed to do for the listener it’s really a nice thing to do."

What sort of kit do you take out for your Tomorrow Comes the Harvest performances?

"I selected the musicians and the sound and function of their instruments so that we aren’t just tied to one direction. They were selected and invited based on the versatility of the instruments they play. Jean-Phi Dary is a pianist but he also knows a lot about electronic music so he can lean more into my direction, but he also knows gospel, afrobeat, blues or classical.

"With our tabla player Prabhu (Edouard), he can do so many different things with his drums… he can play them like percussion, obviously, but he can make them mimic a bassline or create an abstract effect. My set-up is a mixture of many different things. So, I have synthesizers, I have drum machines and live percussion so we’re able to go in just about any direction we think of."

Sadly, we never managed to catch any of your shows with the legendary drumming of Tony Allen before he passed away…

"It was just an incredible experience to play with him and go on tour and record with him. If you’ve been around rhythm your whole adult life then you meet someone like Tony, who came from a totally different spectrum, you immediately realise that there are so many things you still have to learn about rhythm!"

Given your appearance at the CRSSD Festival for 303 Day, when did you first encounter machines like the 303 and your beloved 909?

"In Detroit. At the time I was trying to make electronic music like everyone else. I couldn’t afford an 808 as they were too expensive and very difficult to find. The 808 was a professional type of machine back in the 80s but then they introduced the 909, which was cheaper and more accessible, which I was lucky enough to get one and it started from there. Of course, they then brought out the 303, the 707, the 727 and you just collect them and they became the foundation of my music.

If you experiment with music like I do, then you can look at these machines differently and try and use them differently

"If you experiment with music like I do, then you can look at these machines differently and try and use them differently. That’s what happened to me. So, I can play programs out of the machines, sequence them and use them for a studio recording but I can also play them as a soloist as well, which gave the machines another life."

Having had numerous conversations with people who say that ‘electronic music-makers aren’t musicians’; I generally resort to showing them clips of you playing your 909 such as The Exhibitionist. Was it always your intention to go the extra mile with playing your machines?

"That really comes from my days as a hip-hop DJ. I started DJing with the idea that, of course you can mix the music and make transitions but, if you’re tactful and you practise enough, you can do things with the music to create something that wasn’t originally there.

"I became a DJ in that era so, whether it be turntables, a mixer, a drum machine or synthesizer, I’m always looking at it differently and looking at what I can do differently with it to create something new with it. The whole idea of an album or a 12” or what a track is supposed to be, I’m always looking at what more I could do to it to make it more of an experience.

"We’ve done so much with these machines, and we’ve done so much with electronic music that I wouldn’t be too surprised if musicians found a way to be able to start looking at these machines differently and start redefining our relationship with them, because they can do much more than just be programmed and just hit play to play the sequence.

"What I did with the 909 on The Exhibitionist was just a small fraction of what I think could be possible. I’m always waiting to see musicians using things differently. Not just playing them but redesigning the relationship with them."

What do you think is so special about a lot of the early Roland gear that keeps it so special in our hearts…particularly when things like the 303 only sold about 10000 units when they came out?

"Without wishing to devalue what instrument manufacturers are doing, these older machines were simpler. They weren’t perfect machines; they had some limitation but it was that limitation that required you to be creative and come up with an idea of how to make it sound different than the next guy. When I think of some of the new equipment available today, it’s a little overwhelming all the things you can do… it’s endless!

I’m not always in a rush to go out and get the newest thing as I still prefer to work with the older pieces of equipment and find new ways to make them sound different

"You don’t have any more problems; the tech has solved all the problems. Those older machines were things for you to write and create with, similar to the new machines but instead of allowing you to do one thing, the new ones allow you to do ten things.

"As someone whose been buying and collecting pieces and instruments for decades I still tend to favour the machine that does one simple thing. And when I put that with another machine that does one simple thing…. (laughs) the three of us have to work it out.

"So, I’m not always in a rush to go out and get the newest thing as I still prefer to work with the older pieces of equipment and find new ways to make them sound different and do different things. I’m waiting for instrument makers to make that simple piece of gear that does that one thing brilliantly… like a 303. There’s no sound like it. We know that it was supposed to be like a bass line but (laughs) what kind of bass is that, right?"

Have you done much investigating of the software versions or the clones of the 303 etc?

"Yeah, and some of them are incredible. It’s endless what you can do with the plugins. Someone recently asked me if I missed vinyl records and my answer was yes but that I also missed having a box that limited how many records I could put into it. It was only 65 records in a normal record box, so those records had to be really good. The artist had to have more than one good track on those vinyl if you wanted to keep people interested.

It’s slipping away. The art of ‘the mix’ is going away with a certain generation that grew up with it…

"I miss everything about vinyl, the timing and the time it took to sort through records to find the one you wanted, and, in the process, you would find something else and so you’d play that. Those kinds of things don’t really happen in the digital realm. So, if you applied this thinking to equipment or instruments then it’s kind of the same thing, really. When you have those limitations, it forces you to get creative."

Do you think we’re losing the art of beat-matching due to what technology allows us to do?

"Yeah, I think it’s slipping away. The art of ‘the mix’ is going away with a certain generation that grew up with it… that’s how we started. I don’t hear the art of the mix so often from younger DJs - they just make the transition then once they get into the track, they just let it play. Most don’t seem to think that more should be done to it other than maybe take the bass or the claps out. Layering things together or restructuring the music to make a version that doesn’t exist; that knowledge is slipping away."

Might seeing you working three turntables might give some younger DJs a panic attack?

"You can explain to other people the value of three or four turntables; you can layer them together, you can take frequencies from each one or create a master-mix. Part of the fantasy of dance music is losing yourself in it so when the listener can’t tell when something’s coming and something’s leaving then you’re being more effective in this method of programming music. If I try to explain the value of that, one might reply that it might not be necessary.

"Some might say, why try to mix 3 or 4 turntables when the computer can do it? That's a valid point. My reply would be that there’s a human element to it… you’re playing music to other people not to other machines. Your human response to trying to operate 3 or 4 turntables translates more realistically to people. I think that frame of ‘question and answer’ can be applied to many other aspects of dance music, but we can’t forget that we’re playing music for people.

"People have senses and feelings, and they can tell when you’re trying to do something with the music to make them feel an experience. They can tell that, you know, so if you take that out and your make everything perfect then there’s no excitement to the process."

There’s a worrying trend in the UK at the moment of dance music venues struggling or even closing. How do you think electronic music can best adapt to this?

"It’s always been a rollercoaster… one market's up then the next market's down, you know? Some aspects of dance music are healthy while others are almost non-existent. (laughs) I don’t mean to be a Debbie downer, but it’s been a long time since most factors of electronic music and dance music really worked. When selling music was healthy, being a DJ, touring, clubs and festivals. It’s been quite a while since all those factors have been healthy.

"I’ve seen really wonderful genres of music come then fade away in my lifetime. Enough to know that electronic music is something that we should not take for granted that it will always be here. So, when things are working, we neglect or can’t quite see the things we need to do to keep the artform healthy. It’s not always about being on the front cover of magazines, the Top 10 or making money. There are parts of the artform and the house of the artform that need to be taken care of.

"You can’t just live in a house and simply enjoy living there. Sometimes you have to do some housekeeping. So, we don’t really do those things and we never really did. We never really worked to create the components that any genre of music really needs to be able to translate who an artist is and what he does to people that don’t even know that artist is even there. Maybe it was too loose and too underground and obscure, but we never tried to define what is good.

"If an artist is doing something really amazing, then we should be able to read about what it is about them that is so exceptional its breaking boundaries. That’s then something we can hold up to the rest of culture to say, ‘see, this is what we’re worth’. We never really invested in creating those type of vehicles and then along comes social media and they take it in a whole different direction where it’s not even about the music anymore, it’s about the person and what they look like. We don’t even ask what exactly they’re doing anymore!

"It’s a hard question and an even harder answer that I can’t fully answer, but I think we will see more consequences of not doing the things that we knew we should’ve done, but maybe didn’t because we were partying too much."

Is AI an existential threat to the dance world?

"First of all, I think that there would have to be a great demand for what AI offers. How many people are really wishing to have a mix or a version of someone that didn’t actually do it? I’m not sure, you know? It all really depends on the demand - is it just as good or even better than what the original person did? That’s got to be a question too because we live in a world where we still keep authenticity around us.

"Maybe we’ll still want the person that’s living and still able to make music… of course computers and AI can simulate it, but that’s not what the person made, it’s what the computer calculated that a person like that would make. So, I guess it comes down to whether AI can make something so amazing that I couldn’t make anything like it myself. Ultimately then my answer is no, I don’t see AI creating a threat to the art of creating something from nothing."

Cutting back from lofty concepts like AI, we wondered what instruments or software you currently find yourself using most?

"Just the standard sort of Korg Mono/Polys and old Moogs with that crisp, heavy sound… nothing really unusual. I have newer pieces and special things but what I’m using most of the time is really very simple because it’s about what you do with it. I can’t even tell you how many tracks I’ve made with a 909 and they don’t all sound the same. When you run the sounds into the board and you’re using outboard then you have so many ways of modifying the sounds, so I tend to stay around the old classics."

Any time this hack hears the phrase ‘Mono/Poly’ it gives bad flashbacks to having an original one which was traded in to finance the purchase of a Yamaha DX!

"Yeah, but the DX7s were great machines - I made The Bells on the DX7! The Yamaha DX7 was a machine that everybody had in Detroit at that time. They were reasonably priced; it was small and had a lot of sounds in it for that time. Yamaha were doing some really nice synths and drum machines at that time so you would pair them together. All the early Underground Resistance stuff was done with DX7… (laughs) so maybe that was a fair trade, man."

Given your renowned love of science-fiction, if you were offered the chance to do a gig on the ISS or one of SpaceX’s flights would you do it?

"(laughs) Of course…. it would be worth it just to see Earth from another perspective, and to maybe understand in a more profound way just how fragile this planet is and how small the land mass we occupy and the distance between us actually is."