James Wiseman became an NBA champion on June 16, and he promptly did what NBA champions of this era do: He fired up Instagram and posted a photo of himself cradling the Larry O’Brien trophy. It was a poignant image, with Wiseman pitched forward, gazing downward and seemingly deep in thought, mimicking a pose by his idol Kobe Bryant on a similar night many years ago.

“The greatest experience of my life,” the 21-year-old Warriors center says, reflecting on the moment. “Knowing that you're a champion, and just experiencing that at a young age, like, that’s crazy.”

But then, this being the age of social media snark, came the predictable flood of derisive replies below the photo. Bro didn’t play a single second and is posting the ring. … What did you do to deserve this huh? … This a joke? And on and on it went across the interwebs, for the next many hours.

The backlash was cutting, rooted in a painful, incontrovertible fact: No, Wiseman had not played—not in the six-game Finals victory over the Celtics, nor in any playoff round that preceded it, nor in any game last season, because of a knee injury that, all told, kept him sidelined for a year and a half. And though Wiseman casually bats away the grade-school taunts today—“That's negativity, and I don't feed into negativity”—it’s harder to dismiss the basis for them, or the conflicting swirl of emotions bubbling beneath the champagne showers.

Joy, sorrow, exhilaration, anguish, fulfillment, frustration … all at once.

“Because I didn’t get to contribute,” Wiseman says now. “As an athlete, that’s super hard to go through. … But man, it’s like a blessing in disguise, because of all the rehab I went through and all the work I put in that people didn’t see.”

He adds, softly, “I felt like it was worth it in that sense.”

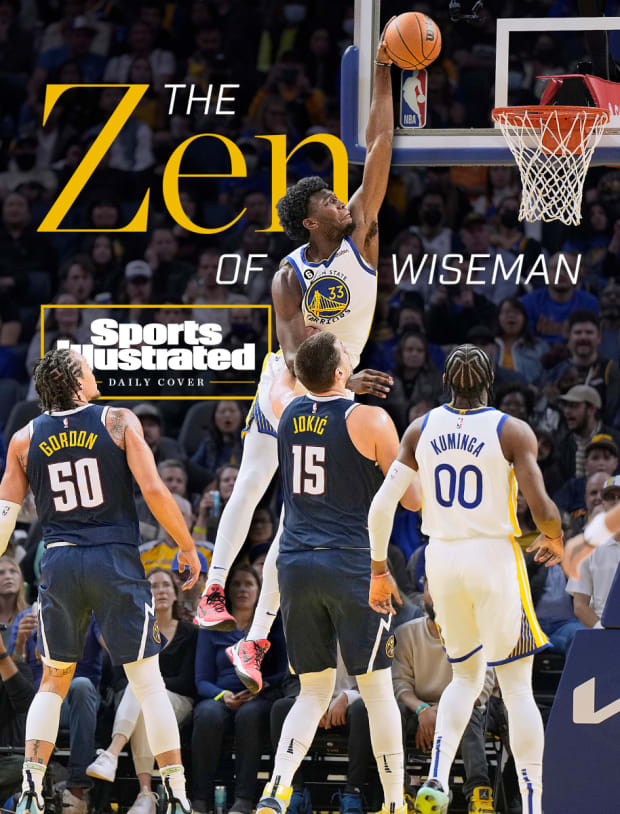

Thearon W. Henderson/Getty Images

Worth it because, two years after Golden State made him the No. 2 pick in the draft, Wiseman is at last healthy, thriving and confident—ready to help the Warriors defend their title, ready to show off the skills he sharpened while away, ready to remind everyone why he was such a tantalizing prospect to begin with.

The NBA waits for no one. In the 18 months Wiseman was out, the league crowned two champions and two MVPs, and welcomed two more draft classes of bright-eyed basketball wunderkinds. The Warriors drafted two more promising young talents (Jonathan Kuminga and Moses Moody), and watched a third (Jordan Poole) blossom. Some fans moved on, too, dismissing Wiseman as too frail and too raw, openly daydreaming about an alternate timeline where their team had instead drafted LaMelo Ball or traded the pick for veteran help.

“I have faith in how good I can be,” Wiseman says, broadly acknowledging the chatter without indulging it. “I’m not giving up for nobody. I'm not giving up on my dream.”

There’s a remarkable sense of Zen about Wiseman, as if he were a 10-year veteran and not a virtual rookie with barely a half season of games on his résumé. But then, few players at Wiseman’s age, with Wiseman’s talent, have traveled such a swift and jagged path to a championship parade.

Three years ago, Wiseman was the No. 1 recruit in the country—a bouncy, skilled 7-footer destined for stardom at Memphis; he played just three games before the NCAA ruled him ineligible over recruiting violations. Two years ago, the Warriors made him the No. 2 pick in the draft and their most exciting prospect in a decade; he missed most of training camp because of COVID-19, lost three weeks to a sprained wrist and played just 39 games before a knee injury ended his season. One year ago, Wiseman seemed primed for a return … until swelling in the knee prompted a second surgery and, eventually, a lost season. And worse.

“I love basketball so much that it kind of turned into my enemy, in a sense, because it kind of drove me crazy [not to play],” Wiseman says. “Mentally, like, I was kind of losing it a little bit.”

He sought therapy for the first time; leaned harder on his family; threw himself into meditation, books, and prayer—anything to keep his mind occupied and his spirit up. So, yes, when that final buzzer sounded at Boston’s TD Garden in June, as the champagne flowed and the music boomed, Wiseman savored every second, having earned it his own way.

On Tuesday, Wiseman received his championship ring, along with his teammates, then claimed an even greater reward: He played 17 minutes in a season-opening victory over the Lakers, collecting eight points, seven rebounds and a block in his first regular-season appearance since April 10, 2021.

It was Wiseman’s first game in a packed arena (due to COVID-19 restrictions in early 2021), which followed his first preseason games, his first full training camp and his first Summer League. In a sense, he is just now starting his career, albeit with a unique profile: a No. 2 pick surrounded by superstars, a prodigy without all the pressure, a champion with a chip on his shoulder.

The burger stand in the casino lobby is packed on an early July afternoon, but 7-footers don’t just amble through without notice. A handful of young fans, presumably here for the Las Vegas Summer League, quickly swarm Wiseman in search of high-fives and selfies, which he happily obliges.

To be a member of the Warriors, teammate of Steph and Klay and Draymond, presumed heir to a dynasty, is to be an instant celebrity, with all the perks and expectations that come with it. The night before, Wiseman had played his first Summer League game, putting up 11 points, two rebounds and two blocks in 19 minutes—a modest first step in his comeback, a minor glimpse of the promise he still holds.

Simply put, the Warriors have not had a center with Wiseman’s build, wingspan, athleticism, mobility or touch in, well, decades. He has the strength to finish inside, the springiness to dunk over anyone, a reliable faceup jumper, a knack for shot blocking at the rim and the agility to defend away from it.

Even after his truncated college career, Wiseman had scouts and pundits swooning in 2020, with ESPN analyst Jay Bilas at one point calling him the best prospect of the draft class, ahead of eventual No. 1 pick Anthony Edwards. “I think he could be special,” Bilas told a Bay Area radio station in May of that year.

Nothing has changed since, except the injuries, and team officials remain just as effusive about Wiseman’s potential as they were on draft night.

“It’s still there,” general manager Bob Myers says. “It has to be realized, but it’s still there, just because he’s that talented.”

With Stephen Curry, Klay Thompson and Draymond Green creeping through their mid-30s, the Warriors are already planning for a future built around their bright young talents. Poole is already flirting with stardom and Sixth Man of the Year candidacy. Kuminga and Moody showed flashes as rookies. But it’s Wiseman, by virtue of his size and skill and draft position, who still has the highest ceiling.

“I’m a huge believer,” coach Steve Kerr says. “I think it’s going to take some time, but I think just given the whole package, he’s gonna be an amazing player.”

Noah Graham/NBAE/Getty Images

The optics, however, have been a bit rough for everyone. While Edwards was bursting into stardom in Minnesota and Ball—picked one spot after Wiseman—was dazzling fans with his passing savvy in Charlotte, Wiseman was hobbling around the Warriors’ glitzy new practice facility and struggling at times with his mental and emotional state.

The first blow came last December, when he needed the second knee surgery. The second came in March, when his G League rehab stint was cut short because of another setback. “It kind of took a toll on me mentally,” says Wiseman, sitting in a quiet hotel conference room a day after his Summer League debut. He sought out a therapist for the first time, which, he says, “worked out for me a lot,” and began writing in a journal “just to express my emotions and feelings.”

And he spent countless hours on the phone with his mom, Donzaleigh Crawley, and his older sister, Jaquarius Howard.

“It was heartbreaking,” says Crawley. “But I did tell him, ‘It’s all right to cry. This is the way you’re supposed to feel. This is not about being a man or not being a man—you’re hurt.’ Not only physically, but mentally he was hurt, too. I had to jump on a plane a lot, go down and make sure. He would tell me he was all right. But me being Mama, I could hear it in his voice and know he wasn’t all right.”

Through it all, it wasn’t the skeptics and critics who weighed on him. It was his own voice, “a battle with myself.” When he hobbled on crutches to the bathroom in the middle of the night, “The only person that I seen in the mirror was me,” he says. “So that means I’m in competition with myself. ‘O.K., James, what you gonna do? You gonna respond? You gonna give up? Or are you gonna keep going through this and just stay strong?' And that’s what I did. I stayed strong.”

Wiseman passed the idle hours watching basketball documentaries (mostly of Kobe) and reading books (including Phil Jackson’s Eleven Rings). He started every morning with a meditation session and a Bible reading to give him a sense “of peace and calmness.”

And he sought out anyone who could teach him how to cope. He called Dejounte Murray, who tore his ACL four years ago and came back to make the All-Star Game last season. He drew inspiration from Thompson, whom he’d watched work his way back from Achilles and ACL injuries over a two-year span. And he spoke often with Shaun Livingston, the former Warriors guard, now a team executive, who overcame a devastating leg injury early in his own career and went on to play 11 more seasons.

“I know what that feels like, when you’re isolated and you’re injured … where you don’t feel like part of the team,” Livingston says. “The doubt, the confusion, all the questions, the why me?”

His advice to Wiseman was simple: Keep your mind occupied and give yourself some structure. Livingston sent him podcasts and gave him self-help books: The 5AM Club (subtitle: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life) and The Power of Now.

“He’s a thinker,” Livingston says of Wiseman. “And sometimes you can self-sabotage.” He adds, “I want him to make himself proud and make himself fulfilled. Ultimately, that’s what mental health is.”

This past summer brought relief and a renewed joy. Wiseman played four games in Vegas, each one bringing a mix of nerves and excitement, some eye-popping dunks and some clumsy misplays, the signs of an athlete who’d barely plied his trade for two years (or three, counting the lost year at Memphis).

Wiseman spent nearly the entire summer at the Warriors’ practice facility, working with development coaches Dejan Milojević and Jama Mahlalela and scrimmaging with a group that included Poole, Moody and Kuminga.

“I think he’s in a better place mentally, because he’s just on the court,” Livingston says. “I mean, you know, he’s freed.”

Thearon W. Henderson/Getty Images

By the time the Warriors landed in Tokyo for their first preseason game, Wiseman had found a steady rhythm and a burgeoning pick-and-roll partnership with Poole on the second unit. He exploded for 20 points and nine rebounds in just 24 minutes in a victory over the Wizards, a moment he describes as both emotional and gratifying because, “I felt like I had to prove myself right, to see if I could still play against NBA talent.”

“He can be a dominant presence and a dominant figure,” says Warriors vet Andre Iguodala, who has been most impressed with the poise Wiseman has shown throughout the last 18 months. “Most guys would have been broken already. You get drafted No. 2, you gotta live up to the hype. You gotta score a certain amount of points.” But Wiseman, he says, hasn’t fallen prey to any of it.

“There’s some lessons you need to learn while you’re a punching bag at times in the league, and it’s not easy,” Kerr says, “but it’s one of the things I’m most proud of him for.”

Wiseman describes himself as “raw” and his career to date as “choppy,” with a “weird road starting off,” but then he remembers another Kobe moment he saw online, this one a video in which the late Hall of Famer notes, “Everybody has a different puzzle, man. You just got to figure out your own puzzle.”

“So it just comes with time,” Wiseman says. “Everybody got a different story. But [what] matters about the person is if you’re willing to not give up and just go through it. So I’m willing to go through it, because I want to be the best.”

Somewhere, in a paper bag stashed in a closet, there’s a massive black warmup shirt with the phrase “ALWAYS BELIEVE” in white lettering—and a rip from the neck to the bottom seam. Wiseman wore it in a predraft workout two years ago. The rip tells a story.

Wiseman was dominating the session. His defender, tired of getting dunked on, wrapped him up in midair on the next drive, nearly injuring him and prompting coaches to end the game. Wiseman stopped, took a couple of breaths, then shredded his shirt—a peaceful alternative to shredding the other player.

“He’s calm,” says Aaron Winshall, the skills trainer who was working with Wiseman then (and who still has the shirt, which he’s mended and plans to present to Wiseman as a gift). “I thought James showed a lot of poise and patience and maturity.”

There’s a quiet, controlled ferocity about Wiseman, and it’s powered him through all the months of rehab and solitude, all the tedious daily steps it took to regain strength and confidence and timing. He’s stronger now and more fluid than he was in his truncated rookie season. He’s refined his footwork, sharpened his defense and absorbed countless lessons from starter Kevon Looney, who if all goes well will one day cede his job to Wiseman.

“His court awareness offensively has dramatically improved,” Kerr says.

On defense, Wiseman is mostly being used as a “drop” defender for now—allowing him to hang back in the lane as a rim protector—to keep things simple. But he has the agility to switch pick-and-rolls and defend guards on the perimeter, which, when he’s ready, “would change everything,” Kerr says.

But that, like everything else, will take time and reps, and everyone has to keep reminding themselves that Wiseman is still just a 21-year-old who’s played 43 official games since graduating high school in 2019. Kerr admits he “threw too much” at Wiseman his rookie season, contributing to some early struggles and early criticism. (“Brain overload,” Wiseman says.) Kerr adds: “So we’re trying to simplify things now.”

The Warriors have a rare advantage for a team with a top-two pick: They have rings and superstars and the luxury of time and patience. Wiseman doesn’t have to play 35 minutes or put up 20–10 every night or play savior. Not for a while.

“That’s a blessing and a curse for James,” Kerr says. “I think it’s more blessing, because he’s gonna learn winning basketball, from guys like Draymond and Steph and Looney. In a lot of ways, he’s going to be allowed to develop in a much more organic, natural pace.”

Which, Wiseman says, is perfectly fine with him. “It’s gonna be a long process for me,” he says. “I’m willing to embrace that and accept that, because I want to be great. So I’m willing to do whatever it takes. … I don’t care about the ego stuff, about the No. 2 pick stuff. I've been through so much s--- that, like, I just want to get better.”

Patience perhaps comes a little easier when you’ve just been fitted for a 140-gram, diamond-encrusted wad of gold, with Splash Brothers for teammates and all the belief in the world that another Finals run is just around the corner. And, frankly, when you’ve already been through some of the worst moments an athlete can endure.

Looking back on that celebratory night in June, what Crawley remembers most is her son’s smile. “As a mom, it was a smile that says, ‘O.K., I got this. I’m gonna try my hardest to bring us back to this.’ ”

On this count, Wiseman offers no restraint or false modesty about his near-term goals. He wants “another championship—back-to-back.”

“And it’s gonna be better this time,” he says, “because I’m gonna be out there playing, actually playing.”

He wants that feeling again. To cradle the Larry O’Brien trophy again, pose for the cameras, pick the best shot and send it out into the ether, haters be damned.