The early 80s were a time of uncertainty for Don Henley. “I felt tremendous pressure, not to measure up to the success of the Eagles, but simply to write and record without them,” he tells Classic Rock, in an exclusive interview. “Having a solo career was something I’d never considered. I felt unmoored, adrift.”

The Eagles had split in 1980, and all the members began to pursue solo careers. Henley’s debut album, 1982’s I Can’t Stand Still, had been a promising, if tentative, step forward. “I think it was a decent first effort,” he says. “In retrospect, a couple of the songs don’t hold up, but that’s true of all my albums.”

Around the time Henley started to gather material for the follow-up, in 1983, the drum machine was redefining the sound of music. “I had mixed emotions about the new electronic instruments,” he admits. “But Danny [Kortchmar, his post-Eagles collaborator] was knowledgeable about all the modern gear and was keen to incorporate it into our writing and recording process.”

Little did Henley know that a LinnDrum machine, acquired by Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers guitarist Mike Campbell, was about to propel his solo career to a new high. On his YouTube channel, Campbell recalled how his first experiments with it inspired the track for Boys Of Summer. “I stayed up all night typing in tambourines and claps and snares. I got a little pattern going, then I came up with that melody line on the keyboard.”

Campbell added guitar and bass, then a week later he played his demo for Tom Petty and producer Jimmy Iovine. But it was rejected as a possible Heartbreakers song for being “too jazzy”. Campbell put the tape on the shelf, and there it might have stayed..

Athough Henley and Campbell have different memories about how they first met, Campbell recalled bringing a cassette of the track to Henley’s house. “We sat at opposite ends of a long table, and he put the cassette on. He didn’t tap his foot or move his head. Just sat there, with his arms folded. He listened all the way through. Ithought he hated it. He goes: ‘Okay, I’ll see what I can do with that.’ And I left.”

Henley says: “People I work with will tell you that I’m not very demonstrative, at least until most of the pieces fall into place. I liked the percussion Mike had created with the machines. I liked the guitar sounds a lot, and the synthesiser lines. All the layers merged into a texture that was really evocative. It just needed a little arranging. Once I’d figured out what went where, the melody and the lyrics began flow pretty quickly.”

The Boys Of Summer was the title of Roger Kahn’s best-selling 1972 book about baseball. But Henley’s reference reached back further. “Even though I am a baseball fan, I had never heard of that book. My inspiration came from the Dylan Thomas poem, which begins: ‘I see the boys of summer in their ruin.’”

Henley’s lyric yearned with a similar ache of lost innocence and youth. Was it written to a specific person? “Some of my songs are, but not that one,” Henley says. “Regardless of the inspiration, or the muse, I try to keep the themes universal. It’s best if songs have an element of ambiguity.”

In the final verse, the memorable line ‘Out on the road today, I saw a Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac’ effectively summed up a whole generation and how they’d squandered their hopeful vision.

“It was a gift,” Henley says. “It came from that mysterious place that lyrics sometimes come from. I had been stuck on the bridge section; couldn’t get the words, the melody. One afternoon, I was driving on Interstate 405, somewhere south of Sunset, the cassette of the track blaring through the sound system. I looked to my left and there it was: a 1979 Cadillac Seville with a ‘Deadhead’ sticker on the back. It just struck me as ironic, paradoxical, with a little touch of nostalgia, and it went right into the song.”

Working at Record One Studio in Los Angeles, Henley assembled a band of top musicians, including Kortchmar, Steve Porcaro, and Campbell on guitar. Artists can often grow attached to demos (it’s known as ‘demo-itis’), and Henley came in set on recreating Campbell’s track, with all its quirky, offhand charm.

“Mike’s one of those guys who doesn’t like to do the same thing twice,” Henley says. “And I’m one of those guys who, whenever I’m struck by a piece of music, and am inspired to write lyrics and melody, I want any recreation of that piece of music to be a clone of what moved me in the first place.”

As they revamped the track, they encountered technical glitches – a hiccup with the LinnDrum’s memory, an analogue tape malfunction that required meticulous gluing and pasting – but they finally got it down.

Then Henley decided to change the key. “Danny always pushed me to sing each song in as high a key as I could,” he says. “He believed that more emotion got transmitted that way, that it was more impactful.” So they went back into the studio, trying to recapture that “first-pass magic” again. “Mike was not happy about that, either, but he came through,” Henley says.

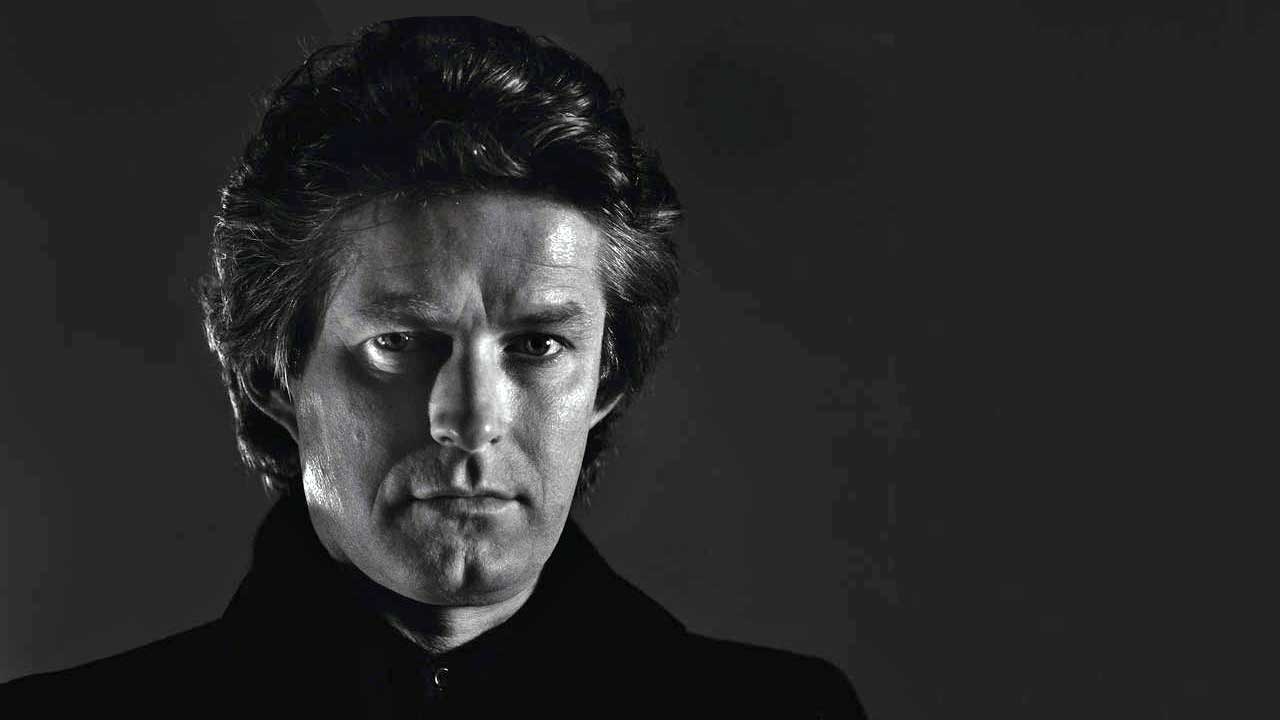

Released in October 1984, as the first single from Henley’s second album, Building The Perfect Beast, it took off immediately. It went to No.5 in the US, and was Henley’s biggest single in the UK, making it to No.12. It benefitted from the moody black-and-white video, directed by Jean-Baptiste Mondino. “He was the only video director I worked with who took the time to consult with me about the song,” Henley says. The heavy-rotation clip swept the 1985 MTV Video Music Awards.

For Henley, his signature song remains “one of the best I’ve co-written”.

“The song is almost forty years old now,” he says. “It’s just another reminder that life is short, but it’s very wide.”