Achieving success outside the established music biz was Marillion’s equivalent of finding the Holy Grail. With no one to please but themselves and their legions of fans, they presented their most controversial recording ever in the form of 17th album Sounds That Can’t Be Made – and as they put the finishing touches on the 2012 release, they told Prog how it had come together over four years.

We really shouldn’t blame mainstream commentators for their laughably warped view of the history of progressive rock. The persistent myth that the genre died on its sorry backside at the end of the 70s and has only just recovered to claw back some vacuous retrospective cool bears little resemblance to the reality, of course.

But for those of us who live and breathe the idea of rock music with no limits, being a prog fan was never about fitting in or seeing our favourite bands receiving recognition from some haughty media elite. We and our music have been here for more than four decades and we’re not going anywhere – are we?

Perhaps the cruellest aspect of the mainstream’s ongoing ignorance is that the one band that can rightfully claim to have bridged the gap between prog’s ignominious near-denouement and its 21st century rebirth are seldom acknowledged as significant to music as a whole. Poor old Marillion, you might say: saviours of prog in the 80s and its most reliable and prolific exponents ever since, they will forever be remembered by the uninitiated as the band that stormed the pop charts with Kayleigh, rather than the fearless, forward-thinking innovators and craftsmen that we know and love.

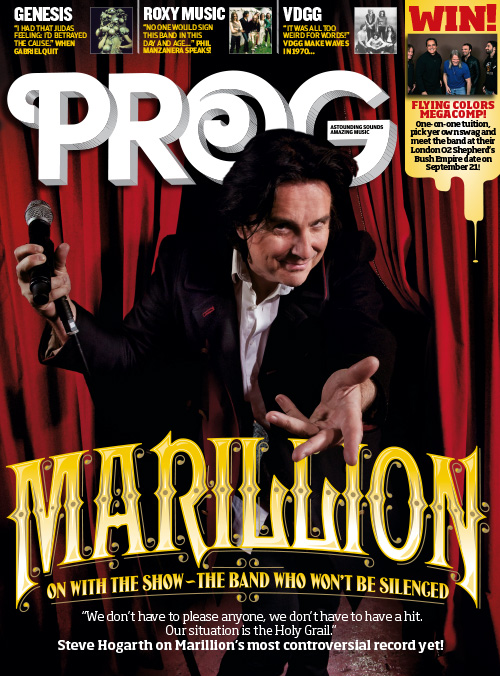

But then again, Marillion really don’t need or deserve anyone’s pity. As they prepare to unveil their 17th studio album, the extraordinary Sounds That Can’t Be Made, the most enduring progressive rock band are in the rudest of health, with a huge and adoring global fan base cheering their every move, and an admirable disregard for toeing the conventional line.

“This situation we’re in, it’s the Holy Grail, to be honest,” says Steve Hogarth, veteran “new boy” and frontman since 1989. “If you’re any kind of creative artist, the Holy Grail is to just do what you wanna do and say what you wanna say with no compromise to business or marketing, and no obvious self-consciousness about the market place, who will or won’t buy your records or how you’re perceived. We don’t have to have an image. We don’t have to have a hit or a song for radio. We’re free of all of those monstrous compromises that most artists have to make in order to continue to exist, so we’re incredibly lucky.”

Freedom has treated the band incredibly well over the last decade or so. Despite their many and impressive commercial triumphs during their early years, it was the moment in 1997 when US fans had a whip-round and raised $60,000 to enable their heroes to cross the Atlantic for a tour that their then label were unwilling to finance that led to Hogarth, guitarist Steve Rothery, bassist Pete Trewavas, keyboardist Mark Kelly and drummer Ian Mosley becoming one of the first major rock bands to embrace the endless possibilities of the online world.

At that precious moment, they began the process of throwing off the shackles of the mainstream music industry and started to mutate into a wholly self-sufficient and remorselessly individual creative collective. Having established Marillion.com long before most other successful bands started taking the internet seriously, they entered the 21st century several steps ahead of everyone else; and, to the delight of their admirers and to the bemusement of their detractors, are now more popular than they have ever been.

“Everything started to change with the embrace of the internet and the website and the fact that we realised – or maybe it was brought to our attention – that our fans weren’t like other fans and they were prepared to take hold of us and support us in a totally different way,” Hogarth recalls. “We realised that we should find out who our fans are.

“We got into a one-on-one relationship with them. Instead of an ‘us-and-them’ relationship, it’s just us now. It’s quite a strange thing; what’s really come out of this piece of digital technology is spirit. We probably started to get a feeling that the internet had that potential to create something really spiritual way back in ’97, before most people in the UK had been anywhere near the internet with a long stick. In fact, people were sneering and pointing at us and calling us nerds.”

Anyone who does anything in a garden shed is branded a nerd and yet garden sheds are where the Alan Turings and the Isaac Newtons start off

Steve Hogarth

With hindsight, it was always going to be the case that the geeks would inherit the Earth. The way the internet has changed the whole world has done genuine underground and non-mainstream art and music a huge favour along the way. While fans of bands like Marillion may still be regarded as incurable nerds by a disinterested media, the plain truth is that progressive rock has more than earned the right to be regarded as a source of innovation, as Hogarth confirms.

“Anyone who does anything in a garden shed is branded a nerd,” he twinkles. “And yet garden sheds are where the Alan Turings and the Isaac Newtons start off, doing their thing. They’re the obsessives, the people who are onto something. There’s no point in sharing that stuff with most people because they wouldn’t understand, so the future tends to come out of sheds!”

Shed-dwellers par excellence, Marillion are about to emerge, blinking, into the sunlight once again with Sounds That Can’t Be Made. Four years on from the mammoth two-disc Happiness Is The Road, this latest full-length has taken a long time to piece together. But even within those years they were far from off the radar. As bassist Pete Trewavas explains, 2010’s album of acoustic reworkings, Less Is More, provided a necessary stopgap to keep the fans happy and to give its creators breathing space while still allowing them to keep the creative juices flowing.

“We did Less Is More as a buffer, because we felt we’d been on this treadmill of writing, recording and then going out touring for album after album, and we’d done that for the last 10 years,” says the bassist. “Marbles was a double album, then we did Somewhere Else and then Happiness Is The Road, which again was a double album, so we produced this huge body of work over a relatively short space of time and we just felt completely drained.

After Less Is More we thought we’d get back on the old writing treadmill, but we were jamming around and it was obvious that we weren’t really ready to start. We should have had some proper time away from each other, but we didn’t. At one point it was all getting tense and very heated, so we thought, just so we didn’t split up we should have time away from each other! That’s why this album has taken such a long time to do. We tried to make it a bit more fun by going away to other places.”

And so that’s what they did. They flew to Portugal to have a stab at writing; and although opinion seems to be divided between those who feel the trip was worthwhile and those who regard it as “a total disaster,” it’s obvious that the higher creative gears required to facilitate the writing of another strong album were conspicuous by their absence.

We don’t talk about stuff as much as you would expect… everyone gets a feel for what’s working and what isn’t

Pete Trewavas

A trip to Italy was aborted, with relations between band members understandably strained by this point. In the end, it would be Peter Gabriel’s Real World studios in the West Country that would provide Marillion with the perfect environment for rediscovering the artistic harmony that has driven them purposefully along for the last two decades.

“Real World is a fantastic studio,” states Trewavas. “It’s like the NASA of recording studios. It’s got everything. The amount of money that Peter Gabriel has spent on the place is alarming! Whatever you want to do and whatever you might want to try, it’s all there in a cupboard somewhere. It’s very uplifting and rewarding, both musically and spiritually.

“It was so nice to get away from everything. We did whatever we could to make it an enjoyable and creative adventure for us. Essentially, we always start the process by jamming and coming up with ideas together. Whatever sparks the imagination and excites everybody, those are the kind of moments we’re trying to capture and put together, if and when they’ll fit. And then we try to make something cohesive.”

“The downside of taking so long over one album is that when you spend three years on a project you get to the point where you start wondering, ‘Is this any good?’” says keyboardist Mark Kelly. “You get sick of some of it. There are certain songs that you think are really good and other bits that you think, ‘Oh God!’ But that’s because it took so long – you don’t really know any more.

“But we do have the luxury of being able to do that. In the past we did go through a phase of making an album a year to keep the bank manager happy, but we’re not in that position anymore, which is fortunate, because it means and we can ask, ‘Is that as good as it can be?’ and then start again if necessary.”

Few bands survive for over 30 years, and even fewer survive with a stable line-up in the way that Marillion have done since recruiting Hogarth and confounding cynics by refusing to lie down and die amid the post-Fish fallout of 1989. The vast catalogue of almost uniformly glorious music that the band have produced since that career stutter must surely stand as testament to their interpersonal and creative chemistry.

It takes a while to get started, like a really old vintage car – cranking the handle in the morning and there’s a lot of noise and smoke

Steve Rothery

The fact that the vast majority of their music is instigated, created and arranged by all five men collaborating together, jamming in a room together and waiting for moments of magic to happen, makes their creative process seem even more remarkable. Yet again, a refreshing alternative to the cynical, written-to-order bilge that dominates the pop charts, a Marillion album seems to evolve entirely organically, propelled along by the optimism and strong will of its ever-enthusiastic creators.

“We don’t really talk about stuff as much as you would expect,” says Trewavas. “Through the process – and in this instance it’s been quite a long process – everyone gets a feel for what’s working and what isn’t. We all tend to have a sense of it, rather than saying, ‘Don’t sing that, it’s bloody awful!’ or ‘For God’s sake don’t play that riff; I hate it!’ We very rarely get into those situations. Things have a way of working themselves out. We try and present things that everybody is excited about.”

As the sole remaining member of Marillion’s original 1979 line-up, Steve Rothery has enjoyed and endured every moment of the band’s journey. He’s willingly embroiled in putting the finishing touches to his guitar parts on Sounds That Can’t Be Made; his enthusiasm for pushing his band forward and his faith in their music’s vitality as potent and unwavering as ever.

“Most bands burn out after a few albums, so to come up with something as strong as this after 17 albums says a lot for the chemistry between us, never mind the talent of the individual,” Rothery says. “We create things together – something quite magical happens when we’re in a room and that process starts. It takes a while to get it started. It’s like having a really old vintage car and cranking the handle in the morning and trying to get it started, and there’s a lot of noise and smoke! And that’s what we’re like for the first year, but then it all kicks off.

“The difficulty is stopping, because you build up this momentum and put yourself in this place mentally where you can create, then you have to stop creating and become more of an arranger – be more focused, which is a whole different mindset. So it’s always a shame that you can’t write one album, carry on and write another one and then finish the first album. Hopefully we’ve created something very special this time. I’m really very confident that Sounds That Can’t Be Made is a really good album.”

Even in their far-from-final incarnations, the songs make up one of the most startling and joyously rounded records of Marillion’s career to date. In fact, it only takes one listen to Gaza, the album’s 17-minute opening epic, to realise there is something different about this album. With an edginess and intensity that few will be expecting from these respected veterans, it’s an extraordinary sonic adventure that ebbs, flows and undergoes multiple transformations throughout its lengthy duration.

I didn’t want to write a song just bashing Israel. You’ve got to keep coming back to the perspective of a child growing up there

Steve Hogarth

Even more significantly, as its title suggests, Gaza explores lyrical territory that may come as a shock to anyone who regards Marillion as fuzzy-headed prog dinosaurs. A bleak, emotionally raw and frequently moving portrayal of Palestinian lives on the Israeli-occupied Gaza strip, the song stops short of being a declamatory political piece – but this is an angrier, edgier Marillion than we have witnessed before.

Hogarth, whose lyrics have become such an integral part of the band’s musical potency over the years, is aware that dealing with such contentious subject matter has the potential to backfire and ruffle many feathers. But, as he coolly explains, this was something he and his comrades felt they had to do.

“I became increasingly aware of the plight of the Palestinian people, especially those held prisoner in Gaza, a few years back,” he says. “I’d seen a few TV documentaries and a few news items, but then I went to see Massive Attack. We were on the guest list and when you picked up your tickets they wanted a donation to the Hoping Foundation. So I went and checked out what it was; it’s simply a foundation that raises money to provide materials and arts education – play, dance, painting and drawing – for children who live in refugee camps.

“That really got my head further into that situation and I started reading about the history of what happened in that part of the world from before the last war through to the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel in 1968, which was actually on my birthday, funnily enough, May 14th.”

Although inspired by the Palestinian situation, Hogarth is not prone to glib sloganeering or superficial statements of empathy. Instead, the writing of Gaza seems to have sprung from a heartfelt desire to get to grips with the facts and reality of a humanitarian disaster that has lasted for decades with no apparent hope in sight.

“I wanted to go over there but I was told that it’s almost impossible to get into the Gaza Strip without a visa, which is almost impossible to get hold of anyway,” he says. “Getting out is a good deal harder than getting in. If I was to go, I might end up having to cancel the rest of the year. So then I began Skyping quite a lot of people from different walks of life within the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, to try and get a sense and feeling of what life is like there.

“I didn’t want to write a piece of naïve, romantic nonsense. I wanted to write something that was factually correct and an accurate reflection. That lyric was slowly being sharpened and put together during the process of making the record. It caused me a lot of sleepless nights – I didn’t want to write a song just bashing Israel. You’ve got to keep coming back to writing the song from the perspective of a child growing up there.”

With its unsettling shifts of mood and tempo, subtle Middle Eastern overtones and persistent core of dogged forward momentum, Gaza is possibly the most unique and affecting piece of music Marillion have ever written. Similar in structure to past epics like The Invisible Man, but more extreme in both tone and delivery, it provides Sounds That Can’t Be Made with a devastating foundation.

If you can tell someone the truth in five words it’ll hit them much harder than 105 words of fiction

Steve Hogarth

“We record pretty much everything we work on together,” Trewavas notes. “We record all the jams and sift through everything that we do, with Mike [Hunter, producer since 2007’s Somewhere Else] as well. We put a lot of things in a folder with other like-minded bits of music, and we found we had a lot of Arabic sounding areas of music that we were getting into. It just worked with what Steve was writing.”

“We’ve all mellowed a lot and the music has probably mellowed with us,” adds Ian Mosley. “It’s hard to be angry young men at our age. But saying that, Steve’s got some pretty heavy duty lyrics on this album, especially on Gaza. Steve was very concerned about it when he first broached the subject, but the more we worked on it, and the more people he spoke to, it just grew and turned into this incredible thing. Sometimes you’ve got to speak up, really, haven’t you?”

Once the gruelling clangour of Gaza subsides, the remaining songs could hardly fail to come across as a breath of fresh air – but even Marillion’s most myopically supportive acolytes may find themselves speechless at the range and depth of emotions and ecstatic melodic peaks that this album offers. From the more straightforward thrills of Power and Invisible Ink, through to the rambling, somnambulant sprawl of the 11-minute Montreal and the exquisite dynamics of the closing Sky Above The Rain, via the Beatles-saluting prog nirvana of Lucky Man, the shimmering art-funk of Pour My Love and the quirky textures of the title track, Sounds That Can’t Be Made is both a thoroughly cohesive and immersive work and a wildly diverse collection of songs that deftly showcase the breadth of vision that Marillion have at their disposal these days.

Above all, this is an album that dares to connect on a profound emotional level: the frequently startling intimacy of Hogarth’s lyrics and delivery blend seamlessly with the intuitive brilliance of the rest of the band’s performances – all notion of predetermined style melt away amid a sustained, celebratory rush of wonderful, life-affirming sound.

“I think if what you’ve written comes from a place where you were moved and if being moved is what led you to write in the first place, the chances are what you write will move other people,” muses Hogarth. “I’m always worried that the purity of the emotion might get lost in a whole load of other musical agendas. As long as the musicians are sensitive enough to what’s being said and play to reinforce that emotion rather than to mask it, it works out well.

“As musicians, we’re very good at knowing how to pluck a heart string, so if I’m saying something that’s emotional, the music tends to amplify that. Our music really rattles people who get it to the core for whatever reason. Without trying to sound pompous, it’s to do with truth as well. If you’re writing truth, it’ll rattle people more than well-crafted fiction – because people can sniff truth. If you can tell someone the truth in five words it’ll hit them much harder than 105 words of fiction.”

Maybe we’re all getting a bit soppy in our old age, but there does seem to have been a considerable upsurge in bands that are unafraid to provoke tears from even their most burly and bearded of listeners. If you’ve revelled in the emotional clout of Anathema’s Weather Systems, or had a private sniffle to The Last Escape from It Bites’ Map Of The Past, you should probably approach the new Marillion album with a degree of caution – because you may end up drenched in snot and unable to operate the kettle.

But some of us have been there before. This writer vividly remembers listening to Marillion’s mammoth Marbles album for the first time and being reduced to a blubbering heap by The Invisible Man, its surreal and shudder-inducingly confessional opening track. If there is a more affecting lyricist than Hogarth operating in music today, will someone please ask them politely to go easy on we fragile souls?

It’s like getting your dick out in public and hoping no one laughs… exposing a very private part of yourself and thinking, ‘Is this too much?’

Steve Hogarth

“I feel privileged to know that you cried, because Invisible Man is a piece of truth,” says the singer. “I’m not clever enough to write something that potent by design. Its potency comes from its truth, and the fact that what I’m saying is about where I was at one point. And it’s about being prepared to expose that as well. I think a lot of people would shy away from parting with that much truth to the world – it’s a very raw thing to do.

“It’s a little bit like getting your dick out in public and hoping no one laughs! It’s that thing of exposing a very private part of yourself and also thinking, ‘Is this too much?’ I thought that when I was writing Invisible Man. There are also some raw moments on the new album. Maybe it’s too much for some people; but the people who get it, they really get it.”

It’s hard to argue: the uniquely direct and intimate relationship the band have with their fans seems to grow in strength with each passing year, as the sold-out shows, fan-sating Marillion Weekend festivals and the many thousands of pre-ordered deluxe editions of the new album would seem to confirm. In an age when music consumers are widely perceived to be suffering from a terminal decline in attention span and loyalty, Marillion continue to be a laudable exception to every rule, making music that challenges and confronts and yet delights an army of adherents. If nothing else, the band’s rise and rise proves that, in spite of the rest of the world, progressive rock fans still believe that music matters, and that there are few more exhilarating sensations than the discovery of something fresh and new to listen to.

“We’re a band that doesn’t have any rules,” says Hogarth. “So we don’t have a rule that says we can’t write a three-minute pop song, and we haven’t got a rule that says we’re not allowed to write a 17-minute wandering piece of diary put to music like Montreal or some kind of manic confession. They’re all within our remit and we’re comfortable in any of those places. We try to keep redefining what you might consider us to be.

“Pour My Love, to my ear, is somewhere between Prince and Todd Rundgren, which is a great place to be – and it’s somewhere we haven’t been before. We get a thrill out of redefining what we might represent. We used to be a bit scared, many years ago. We’d work on a song and see eyebrows go up across the room, like ‘Ooh, maybe this isn’t the kind of song we should be making…’ but that stopped a long time ago and all bets are off now!”

“Sometimes when we’re locked up in the studio for too long, you do forget,” Mosley adds. “Then you go out and do a gig and it’s, ‘Wait a minute, this is what it’s all about!’ And it’s brilliant! Of course, it’d be nice to have mega media exposure, because I’d love to put on a show like Roger Waters or Pink Floyd. That kind of success would enable us to bring out a massive production. I’d love to blow up the drum kit at the end of the gig! But our fans are loyal and forgiving and we love them for that.”

Impervious to time and the tides of fashion, they have the music, the fans and the faith to keep nimbly side-stepping the hollow demands of a music industry that never really understood them. If only one band is allowed to encapsulate the ethos and spirit of the last four decades of prog, you’d have to be a miserly soul to deny that Marillion are the most deserving.

“We have the same hope for this album that we always have,” says Hogarth. “You create this stuff and put it out there. What’s that story in the Bible where somebody sticks a baby in a basket made of reeds and floats it down river? Well, you create this thing that is incredibly precious to you and you float it down the river and hope it’s loved as it goes by, and you hope someone takes it out and looks after it.

“I hope there are enough sensitive souls out there who get what I’m on about and that it hits them in the same part it did for me. And I hope nobody laughs when I pull my trousers down!”

This article originally appeared in Prog 29.