Daniel Stamps thought he would be trying out something new when he logged onto UberEats this June and ordered delivery from an unfamiliar restaurant called "It's Just Wings".

When the food arrived, Stamps says it was "by far the worst wings I've ever seen – soggy and cold, like they'd been sitting in water for two hours".

More puzzling, however, was the fact that they came in a box from Chili's Grill and Bar, a mid-market chain restaurant owned by Texas-based Brinker International.

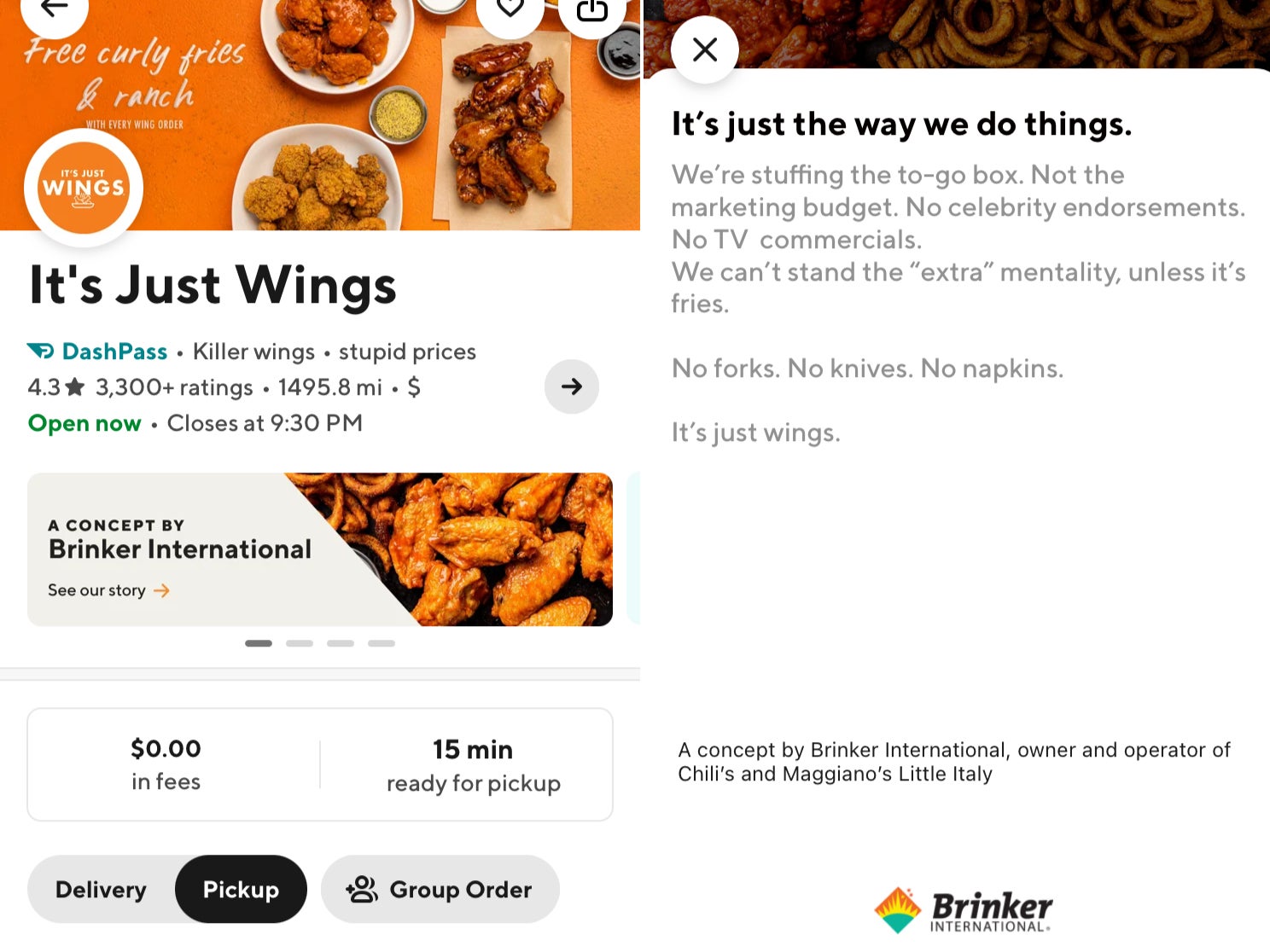

What Stamps didn't know when he ordered was that It's Just Wings is a "virtual restaurant", not only owned by the same company as Chili's but actually cooking its food in the same kitchens. According to Stamps, the food was exactly the same.

"I hate Chili's. I know Chili's wings are awful. I would never knowingly order from Chili's," the 30-something American software engineer tells The Independent. "And yet, while fully convinced I was shopping elsewhere, I ordered from Chili's. To me, it's a clearly deceptive, disgusting business practice."

Virtual restaurant brands based in other establishments' kitchens have proliferated wildly since the pandemic, alongside so-called "ghost kitchens" that have no public seating or frontage and exist purely to fulfill delivery orders on apps such as Uber Eats, DoorDash and GrubHub.

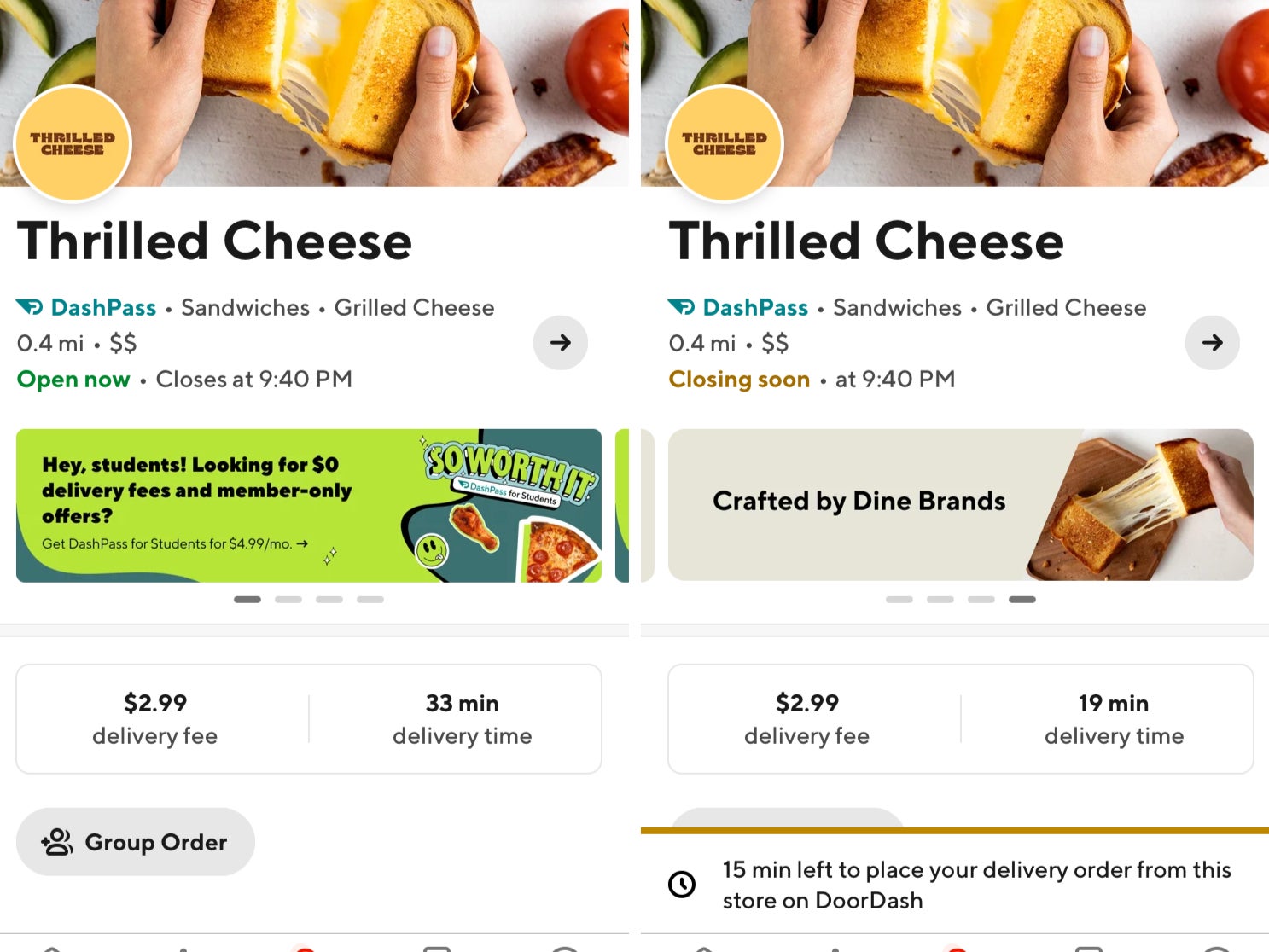

As well as It's Just Wings, there's Thrilled Cheese (run by pancake chain IHOP), Pasqually's Pizza and Wings (Chuck E Cheese), Cosmic Wings (Applebee's), and The Burger Den and The Melt Down (both run by Denny's). Celebrities have also lent their image to virtual restaurants, such as Mariah Carey's Cookies, Guy Fieri's Flavortown, and the now relatively famou MrBeast Burger (founded by YouTuber Jimmy Donaldson, aka MrBeast).

Owners and app companies often describe virtual brands as a way for existing restaurants, still recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic, to try out new food styles while taking full advantage of the facilities and staff they already have. Some operators insist that the food sold by virtual restaurants is genuinely different from that of their parent brands.

"These innovative concepts enable both local and national restaurants to reach new customers, provide more selection in their neighbourhoods, and grow their revenue in a cost-effective way," says a spokesperson for DoorDash.

A spokesperson for Uber said “storefronts are required to follow the same community guidelines of all Uber Eats merchants”. And a spokesperson for DoorDash said “virtual brands are clearly marked and marketed as such. We’re overtly and intentionally transparent with our customers on where they’re ordering from”.

The connection between these brands is almost never clear on such apps. Although DoorDash requires virtual brands to be labelled as virtual, and many do disclose their parent company, none of the examples seen by The Independent actually said they were based in another restaurant's kitchen.

Meanwhile, customers and delivery drivers told The Independent that the practice amounted to "false advertisement" or "a bait and switch", which resulted in customers ordering from chain restaurants that they would never otherwise buy from.

On social media, consumer outrage about virtual restaurants has only grown since the start of the pandemic, with some DoorDash or Uber Eats users now saying it has made them leery of ordering via app altogether.

"I genuinely thought I was supporting a new small business that opened during a pandemic, not a multi-million dollar chain that was doing just fine," says one 35-year-old woman in New Mexico who ordered from It's Just Wings back in April 2020, who asked for her name not to be used.

"I felt very taken advantage of, almost duped ... like they were misrepresenting themselves and their product to take advantage of the fact that everyone was stuck at home so we couldn't physically go check any new restaraunts out. To me, it smacked of dishonesty."

Brinker International, IHOP, Applebee's, Chuck E Cheese, and GrubHub did not respond to requests for comment.

‘It's a bait and switch, plain and simple’

Virtual restaurants are not a secret. The business press regularly reports on new ventures by well-known chains, which sometimes win industry awards, and sometimes customers’ confusion about the practice breaks into mainstream headlines.

Virtual Dining Concepts, the company behind MrBeast Burger and Mariah's Cookies, proudly proclaims on its website that it "offer[s] traditional restaurant owners a low-risk, all-in-one solution to launch a profitable delivery-only concept in their existing kitchen operations, with zero up-front fees."

Its slogan for restaurant owners is: "More money. More sales. Same kitchen."

A spokesperson for Uber Eats said that around 20,000 of the 800,000 restaurants on the app are virtual restaurant concepts, the "majority of which operate out of existing brick and mortar restaurants". The company often works with restaurants to launch new virtual brands, as it did with Applebee's Cosmic Wings.

These restaurants often have a particular style of eye-catching name. Examples collected by Mike Kostyo, associate director of the Chicago-based food industry consultancy Datassential, include “Bad-Ass Breakfast Burritos”, “Burger Slob”, “Pimp My Pasta”, “Phuket I’m Vegan”, “Bad Mutha Clucka”, “F*** Carbs”, and ”F*** Gluten”.

Clearly, however, many customers remain unaware of the practice. On Reddit and Twitter there are countless stories of people feeling confused by virtual restaurants and ghost kitchens, which many users lump together under the latter term.

"I understand the use of ghost kitchens back during the height of 2020, but it’s 2022 now," said one user on Reddit's DoorDash board in July. "As a customer I’m absolutely tired of having to research every restaurant that I’ve not tried yet just to see if it’s real.

"If I wanted to order from the kitchen of some bad quality chain restaurant then I would order from that restaurant. If they’re going to expand their menu then they should expand their menu."

In a different discussion in April, one user described how her truck driver husband, who ate Denny's every night while staying in hotels for work, had tried to order a panini from "what he thought was a local sandwich shop". When this too turned out to be a virtual brand of Denny's, "he wasn't pleased".

Many people argued that virtual restaurants should have to disclose their host kitchen on delivery apps. "At this point, if it’s a place you haven’t heard of, check the address on Google. I forgot to do it this one time and just literally got the worst and most overpriced breakfast tacos I’ve ever had from a damn gas station," said one person.'

Others spoke of feeling "so deceived". One user joked: "If you don't like the food somewhere, you order from somewhere else. And the same food arrives. Twilight zone s***."

For Stamps, having to constantly double-check every restaurant he ordered from was one reason he has now stopped using Uber Eats. In principle, he has no problem with the idea of virtual restaurants or ghost kitchens; in practice, he has found that most of them are "a bait and switch, plain and simple", using the same employees in the same kitchen to cook the same food with the same ingredients.

"The fake restaurant names, menu items, and even websites are all kitschy and unique, which give the impression of a small mom-and-pop operation," Stamps tells The Independent. "In the (in my experience) rare cases where the menu items aren't totally identical, they are laughably similar ... and, of course, all of this is intentionally hidden from the customer."

"The problem is that this is not what restaurants on Uber Eats and other apps are doing. It's the same restaurant, the same food, being sold under a different brand name.... it's a bait and switch, plain and simple."

The woman who ordered from It's Just Wings in New Mexico used similar language, saying she was okay with ghost kitchens and virtual restaurants that genuinely offered their own food, but that the wings she ordered were identical to Chili's wings.

"I had this hauntingly familiar feeling of deja vu," she says. "I knew I'd had these awful wings before. I did some Googling and sleuthing in the Door Dash app, and found out the address it was delivered from was the address of the local Chili's.

"That Chili's had been down the street from my house for 15 years. I knew where it was, it showed up on my DoorDash app on its own already, and I ate there often enough. If I had wanted Chili's, I would have ordered from Chili's. And I wouldn't have ordered the wings."

Delivery drivers caught in virtual chaos

It's not only customers who have problems with virtual restaurants. Delivery drivers say they are often shown no indication in the app that a virtual restaurant does not have its own building, leading them to waste valuable minutes wandering around looking for it.

Take 'Judy', a 37-year-old part-time DoorDasher in the US who received her first order for It's Just Wings in 2021, with directions to pick up the food at a local mall (she asked The Independent to refer to her by a pseudonym).

"I remember walking that mall top to bottom thinking there must be a new restaurant," Judy says. "Finally I just started going in restaurants and asking if they had changed their name recently and that's how I found out 'It's Just Wings' was Just Chili's."

'Rupert', 26, who spent much of last year driving for DoorDash and Uber Eats in Kansas City, Missouri (and likewise requested a pseudonym), tells The Independent that at one point there were four to six virtual restaurants operating out of the same Italian food chain on their patch.

Every so often they would receive an order from what they thought was a new restaurant, only to end up back at the same place again. They say the profusion of different menus being cooked in the same kitchen put extra stress on the already under-staffed workers, causing regular 30-45 minute waits for drivers picking up.

"They were constantly understaffed, and constantly mad," says Rupert. "I hated it, the customers hated it, the workers at the restaurants hated it. It was just irritating and messy and none of this was fun for anyone.

"There actually are some virtual restaurants that are quite nice, and it's definitely food that they wouldn't offer otherwise. But those are incredibly slim."

Time is of the essence for app delivery drivers, who are typically paid a flat fee plus the customer's tip for each order and must ruthlessly assess each order they accept to ensure that they don't accidentally end up working for less than minimum wage per hour.

"I'd be half asleep, just working my tail off, and then all of a sudden, accidentally accept some fake-ass s*** and then have to take a loss for it, or else I'd get penalised [for not completing the order]," says Rupert.

"Past a certain point I just wasn't accepting any virtual restaurants unless [the order] was f***ing gold – like if it was obviously going to have a massive tip."

Some drivers also find that customers blame them for bad experiences with virtual restaurants, in some cases alleging that the driver has given them someone else's order.

"They get mad at me in the ratings sometimes – 'my food was a mess!'" says Judy. "The customer thought they were getting local food. This also hurts local businesses too. Everyone loses, except delivery restaurants and chain restaurants."

DoorDash requires virtual brands to be labelled

According to Datassential, 67 per cent of consumers say a virtual restaurant brand should be required to name the actual restaurant or establishment where their foot is made. Currently, however, none of the major food delivery apps meets this standard.

“Many third-party delivery platforms have made it harder than ever to differentiate virtual brands and determine where the food is coming from,” wrote Mike Kostyo in February. “When consumers don’t know who is preparing their food, they feel like they don’t have all the information they need to make their purchase, and they wonder if the restaurant was hiding this information for a reason.”

Neither Uber Eats nor GrubHub appear to require virtual restaurants to disclose their status or affiliation, according to a survey of listings in the San Francisco Bay Area and other US cities by The Independent.

The only way that consumers can tell such brands are hosted by chain restaurants is to search Google for news coverage about them or to check what other businesses are listed at the same address.

“We know that consumers are looking for more: more choices, more cuisine types, more options, which is why we’re focused on helping to create more quality offerings,” a spokesperson for Uber said. “These storefronts are required to follow the same community guidelines of all Uber Eats merchants.”

DoorDash, by contrast, now requires virtual restaurants to carry a label saying “this is a virtual brand”, or a more specific banner naming their owner. In response to questions from The Independent, a spokesperson objected to the idea that virtual restaurants deceive customers.

“On the DoorDash platform, virtual brands are clearly marked and marketed as such. We’re overtly and intentionally transparent with our customers on where they’re ordering from,” the spokesperson says.

“Our primary goal with this effort is to inform customers where they are ordering... the address of the physical location is on the bottom of each store page as well.”

He adds that virtual restaurants who join DoorDash must provide “appropriate documentation, just like any restaurant partner is required to do”, and follow local health and safety regulations as well as the app’s own rules.

Yet all the DoorDash labels seen by The Independent fell short of actually telling customers that a virtual brand was based in another restaurant’s kitchen.

The banner for It's Just Wings merely describes it as "a concept by Brinker International" – hardly a household name. Tapping or clicking the banner shows an "about page" which says, at the bottom in small print, that Brinker is the "owner and operator of Chili's". Nowhere does it say the two restaurants are more closely related.

The disclosure for Thrilled Cheese is even more cryptic: users must scroll through several advertisements for special officers to reveal a banner that says "created by Dine Brands". Wikipedia will tell you that Dine is the parent company of Applebee's and IHOP, but the DoorDash listing does not elaborate any further.

"While the banners are undoubtedly an improvement from zero disclosure, I don't really find them adequate," says the customer in New Mexico. "If I read that as an unknowing consumer, I would assume this is a completely different franchise chain. In reality, that isn't true."

Judy also poured scorn on the idea that these labels would be any use to drivers, saying that when an order comes in she typically has about 20 seconds to read the name of the restaurant, check the distance and the number of items being ordered, assess the fee and tip, and decide whether it's worthwhile – all while driving on Saturday night traffic.

"Are you telling me you'll have time open a new window to research the restaurant before that 20 second timer is up? Perhaps you'll crash into a biker or something staring at your phone? Hell no," she concludes.

In response to further questions about the labels, a DoorDash spokesperson says: "Yes, we believe that DoorDash is providing fair and transparent notice by labeling the virtual brands on our platform, along with providing the physical address. These two pieces of information allow a consumer to clearly identify if the brand is a virtual brand."

According to Rupert, some drivers have responded to the situation in creative if unscrupulous ways. In Kansas City last year, they say there were sometimes virtual restaurants listed on delivery apps that were no longer in service.

Naturally, a few drivers decided to park their cars and begin accepting orders to these duff restaurants, before calling the app's support line and reporting the problem to get a small compensation payment. Eventually they were caught and kicked off the app.

"There were some people that were making $40-50 an hour," recalls Rupert, "just sitting at one virtual restaurant that doesn't exist."